Abstract

In May 2018, an outbreak of gastrointestinal illnesses due to norovirus occurred at Camp Arifjan, Kuwait. The outbreak lasted 14 days, and a total of 91 cases, of which 8 were laboratory confirmed and 83 were suspected, were identified. Because the cases occurred among a population of several thousand service members transiting through a crowded, congregate setting of open bays of up to 250 beds, shared bathrooms and showers, and large dining facilities, the risk of hundreds or thousands of cases was significant. The responsible preventive medicine authorities promptly recognized the potential threat and organized and monitored the comprehensive response that limited the spread of the illness and the duration of the outbreak. This report summarizes findings of the field investigation and the preventive medicine response conducted from 18 May–3 June 2018 at Camp Arifjan.

What Are the New Findings?

Introduction of norovirus disease into a crowded, congregate setting of transient service members precipitated an outbreak of at least 91 recognized cases in a vulnerable population of thousands. Prompt actions to halt air traffic in and out of the base, to isolate and quarantine infected persons, and to restrict movement to separate the well from the sick aborted the outbreak.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Norovirus is the leading cause of gastrointestinal illnesses in military settings. The contagiousness of the virus and the short incubation period can result in high case counts in concentrated military populations whose mission readiness may be impaired by widespread illness and necessary control measures. Recognition of this illness should prompt rapid and vigorous countermeasures.

Background

Norovirus is the leading cause of acute gastrointestinal (GI) illness outbreaks in military settings.1–7 Norovirus can be transmitted through person-to-person direct contact and exposure to contaminated food, water, aerosols, and fomites.7–9 Additionally, the virus is resistant to extreme temperatures and many standard disinfection methods.9 Following a short incubation period of 24–72 hours, symptoms, lasting 1 to 3 days, may include diarrhea, vomiting, nausea, and stomach pain. Patients recovering from a norovirus infection may shed the virus in their stool for up to 14 days, increasing the risk of secondary infection.7–9

Setting

Camp Arifjan, Kuwait, is the largest U.S. military base in the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) and, at the time of the reported outbreak, accommodated over 10,000 service members from all branches of the U.S. military and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization as well as Department of Defense (DOD) civilians and contractors. Camp Arifjan's gateway serves as the hub for U.S. military and DOD personnel traveling throughout the Southwest Asian Theater. On a daily basis, a minimum of 1,000 personnel are transiting through Camp Arifjan's gateway to return to the U.S. or to travel to other points within the USCENTCOM, making the area highly susceptible to the spread of infectious disease. At the time of the outbreak described in this report, there were approximately 14,000 service members at Camp Arifjan, of which about 3,000–4,000 were in transit and 10,000 were permanently assigned there.

For transient personnel awaiting transportation, separate housing and bathrooms are located within the gateway area; however, transients' movements throughout the rest of Camp Arifjan are not restricted. Dining, laundry, recreation, and transportation facilities are shared between the transient and permanent populations. Housing comprises concrete buildings with beds located in open bays that can accommodate up to 250 people. Latrine and shower facilities are in separate trailers but are also used by those who work within the gateway area. Of the 35 buildings within the gateway, 5 are reserved for latrine/showers, 7 function as administrative offices for the gateway transportation and postal services, 7 serve as offices for the theater engineer brigade, and 16 operate as transient barracks.

Outbreak timeline

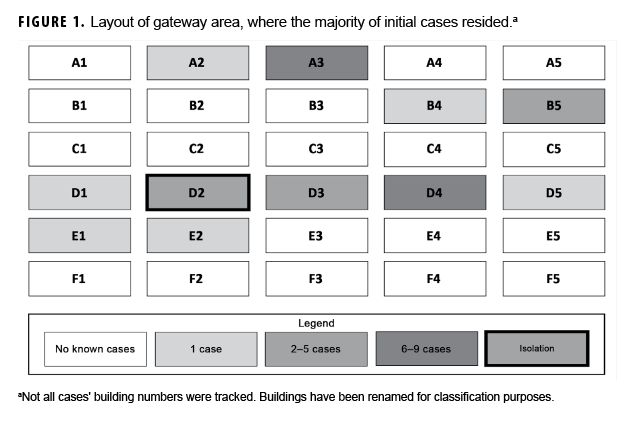

On 18 May at approximately 0800 hours, the 75th Combat Support Hospital emergency department (ED) evaluated a male active duty patient who presented with symptoms of nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. This patient had traveled from a classified country to Ali Al Salem Air Base and then to Camp Arifjan en route to redeploy to the U.S. The patient and his unit had slept outside while at Ali Al Salem and were there for less than 8 hours before traveling via bus to Camp Arifjan. During the 2-hour bus drive from Ali Al Salem to Camp Arifjan, with an estimated 30 other personnel on the bus, the patient vomited and soiled himself multiple times. Upon arriving in Camp Arifjan, the patient was transported by his unit directly from the bus to the ED. In the ED, after the patient was assessed and treated, a stool specimen was collected for clinical testing, and he was released to his unit into the transient barracks in building D2 at the gateway (Figure 1).

The 223rd Medical Detachment (Preventive Medicine [PM]) and the theater PM physician at the medical brigade were immediately notified of the patient, and an aliquot of the stool specimen was transferred to the PM laboratory for surveillance testing via the BioFire® FilmArray® GI panel. Norovirus, enteropathogenic Escherichia coli, and enteroaggregative E. coli were all detected in the stool specimen. The 223rd Medical Detachment microbiologist immediately notified the public health nurse stationed with the 75th Combat Support Hospital. Twenty minutes after receiving the results of the GI test, the detachment commander and the PM physician decided that the index patient was to be immediately readmitted to the hospital. Two hours after being initially discharged, the patient was readmitted to the hospital and put into isolation.

On 20 May, 2 additional cases presented with nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. One case tested positive for norovirus on the FilmArray® GI panel. This case was housed at the gateway in building B4. When interviewed, he reported that 1 of the soldiers who lived in building D2 was also sick. The other case could not produce a stool specimen for testing. Social media postings seen by the PM staff reported anecdotally that other soldiers were sick during this time, but no other soldiers presented to the hospital with GI symptoms, resulting in several days without patients.

On 23 May, an Army unit departed Kuwait and arrived at North Fort Hood, TX, the next day. The soldiers in the unit were not symptomatic upon their departure; however, during the course of the flight, a total of 21 soldiers exhibited symptoms consistent with norovirus, and 1 case was later laboratory confirmed. These 21 cases were not counted in the total case count from Camp Arifjan. All symptomatic soldiers were seen, treated, and released to quarters per the chief of PM at Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center in Fort Hood.

On 24 May, 3 patients presented with norovirus symptoms at the ED at Camp Arifjan; all patients were confirmed positive for norovirus with the BioFire® FilmArray®. On 25 May, a medic arrived at 0500 to the ED to request Imodium® for soldiers in his unit who were sick and were scheduled to redeploy home that day. Throughout the day, 12 patients presented to the ED and clinic with symptoms consistent with norovirus illness, and an outbreak was officially declared by the medical brigade commander, who notified the installation commander of Camp Arifjan. Based upon the recommendation of the theater PM physician, the command authorities and the Air Force agreed to halt flights coming in and out of Camp Arifjan. The flight leaving for Fort Hood mentioned above had departed Camp Arifjan before flights were halted; however, no other flights departed Camp Arifjan until the outbreak had resolved, and Fort Hood reported this incident and response to the Disease Reporting System internet on 30 May. All new cases presenting with symptoms consistent with norovirus were assumed to be part of this outbreak unless proven otherwise. Over the course of 14 days, a total of 91 cases experienced symptoms of nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or abdominal pain while at Camp Arifjan.

Methods

All cases were symptomatically identified. The BioFire® system was used for presumptive testing during the outbreaks in theater. Testing via the BioFire® system was suspended once norovirus was identified in the first 8 cases and thus determined to be the cause of the outbreak. BioFire® testing began again at the end of the outbreak to separate those patients without norovirus to preclude them from the quarantine area in an effort to prevent them from acquiring a nosocomial illness.

For the epidemiologic investigation described here, a confirmed case of norovirus was defined as a patient at Camp Arifjan from 18–31 May who experienced nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or abdominal cramps and whose stool specimen tested positive for norovirus via polymerase chain reaction using the FilmArray® GI Panel for norovirus. A suspected case was defined as a patient having any of the same symptoms as a confirmed case but whose stool sample was not tested. After the index case, individuals who had experienced symptoms outside of Camp Arifjan, including the aforementioned soldiers who traveled to Fort Hood, were not included in the overall case count.

Results

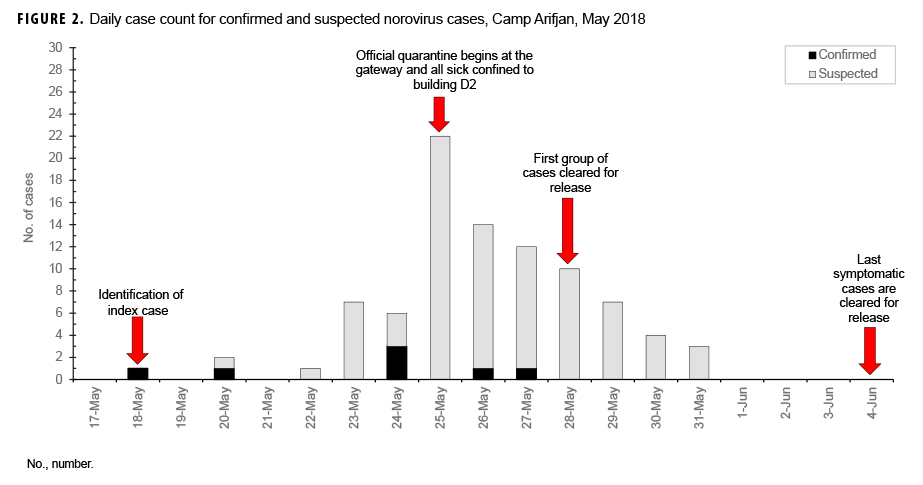

From 18–31 May 2018, a total of 91 cases (8 confirmed and 83 suspected) of norovirus were found in Camp Arifjan, Kuwait (Figure 2). Two symptomatic cases (1 confirmed and 1 suspected) did not have a recorded onset date.

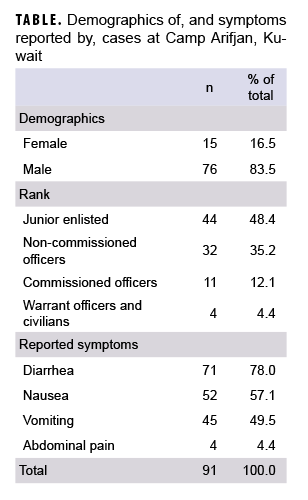

The most common symptoms reported by patients were diarrhea, vomiting, nausea (Table). Most cases were among men (84%) and among junior enlisted (48%) and senior enlisted (35%) personnel (Table). Six cases (6%) had been previously deployed in neighboring countries and had been in Kuwait for fewer than 4 days before their illness onset date. Twelve cases (13%) belonged to 1 unit, which had the highest concentration of cases in any single unit. Attack rates by unit were not available.

Confirmed and suspect cases were symptomatic for 1 day on average (range: 1–4 days). The index case and the last known case were both hospitalized, primarily for isolation purposes. The last hospitalized case was moved from the barracks to the hospital to allow the barracks to be cleaned and opened to house other service members again.

Countermeasures

On 18 May, PM made initial recommendations to the gateway staff to limit the number of new service members placed in building D2. The staff refused because of overcrowding and the need to place service members in beds. However, in the effort to reduce the spread of infection, signs were placed that evening by the 223rd Detachment team on building D2 and the closest men's bathroom. It was later ascertained through patient interviews that the precautions on these signs were generally ignored.

On the evening of 18 May, PM specialists were sent to observe cleaning contractors while latrines were being disinfected and to oversee the cleaning dilution used. The cleaning contractors were directly observed using toilet water to mop and clean the bathroom sinks. On 19 May, PM notified the base contracting officers about the unsanitary cleaning practices and the potential of an upcoming norovirus outbreak, emphasizing how improper cleaning practices exacerbate the spread of disease. No changes were made to the cleaning schedule to disinfect those sinks until after the outbreak had started.

Daily briefings were held to keep all health care providers, medics, and cleaning teams informed. These briefings provided information to help facilitate the plan for the next 12–24 hours, including a reminder of the cleaning protocols and updates on the status of housing, food, the cleaning of latrines, and the numbers of service members who were quarantined, cleared, or with active symptoms.

On 25 May, at the recommendation of the theater PM physician, all flights departing Kuwait were halted and a 72-hour quarantine at the gateway was initiated. An incident commander worked closely with base stakeholders to ensure infection control measures were implemented while medical care, security, food, and other accommodations were provided for the more than 1,200 personnel housed in the quarantine area, which included the 30 buildings shown in Figure 1. Building D2 was designated the isolation building for all newly identified sick cases. That building was chosen to isolate symptomatic patients because the index case originally slept there and all service members residing in that building had potentially been exposed. The building was also chosen because it was closest to the latrine that had already been used by several confirmed cases.

The same day, the theater PM physician recommended a tiered approach to isolation and quarantine in an effort to control the spread of disease by placing all service members into 4 groups. Group 1 consisted of symptomatic cases who were isolated in building D2. Group 2 comprised those recovering from GI illness who were isolated in another building for an additional 24 hours after symptoms resolved. Group 3 included exposed service members who had not exhibited any symptoms but were being contained in the D and E blocks during the length of the incubation period (72 hours). Group 4 was composed of others in the general population who never exhibited symptoms and were not knowingly exposed to the ill population. Groups 1–3 remained inside the quarantine area, and most were released by 29 May. Service members in group 4 were free to move throughout Camp Arifjan but were restricted from entering the quarantine area. Barricade tape sectioned off the approximately 300 yard perimeter, and military police secured the perimeter to prevent service members from entering or leaving the quarantine zone.

On 28 May, survey forms (Figure 3) were developed to expedite the screening process for medically clearing service members. Providers and medics were recruited from the quarantined units to assist with administering the survey in the quarantined area. The form was designed to be cut in half so that service members could keep a copy and use it as their ticket to leave the quarantined area and move freely within Camp Arifjan if they had been medically cleared to do so. Two health care providers, 20 medics, and 1 public health nurse administered the surveys to the service members who were billeted in the quarantine buildings. Two PM technicians were assigned to each row of quarantined buildings. PM technicians and the public health nurse instructed cleaning teams in each building on the mixing of bleach solution and proper cleaning procedures, according to guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. All personnel were medically evaluated and all buildings were sanitized by 2300 on May 28. At 2400 that evening, the quarantine area was reduced to building D2, where sick personnel remained, and to specified bathrooms.

Editorial Comment

The operational impact of the outbreak at Camp Arifjan was dramatic. Not only was there a surge in illness among service members in transit, the definitive steps taken to preclude the spread of the contagious virus elsewhere resulted in the shutdown of a key USCENTCOM transit station for about 10 days. The unique setting and circumstances of this outbreak highlight several public health gaps faced by deployed service members and those providing health care in this environment. Because no outbreak investigation standard operating procedure (SOP) was in place before this outbreak, the investigation and response were implemented de novo. The absence of an SOP for handling outbreaks is an acknowledged gap across many military treatment facilities, both within the U.S. and in deployed operations.10 The lack of an SOP delayed the initiation of an outbreak investigation by PM and nursing teams. The outbreak highlighted that cleaning staff were not initially using proper techniques to disinfect the latrines, which may have contributed to additional cases. The size of the outbreak and the concomitant tasks of identifying, finding, treating, and responding to the high number of cases overwhelmed the PM staff and directly impacted the delay in reporting details of this outbreak according to DOD policy until the outbreak was nearly over. An approved theater outbreak response plan is needed in order to help mitigate and prevent future outbreaks in theater. Such a plan should be centrally drafted at the level of the medical brigade, not by each unit or location. A general response plan should be encouraged for each location, but the PM assets and expertise required to manage an outbreak may not always be available at each location.

The physicians at the 75th Combat Support Hospital who evaluated and treated the index patient released him to return to his billeting. However, in a deployed environment, a significant consideration is to protect the force by removing patients who are potentially infectious from the general population. Although the theater PM physician and 223rd PM commander were able to identify and readmit the index case within 2 hours of his ED discharge, it is unknown how many others the index case may have exposed during this time, especially given the poor cleaning procedures being utilized during that period. A theater outbreak response plan must include specifics for protecting the health of other service members when one of them is ill and may be highly infectious.

Laboratory capabilities are limited throughout the theater. For most diseases requiring laboratory support, specimens are sent to Landstuhl Regional Medical Center for processing, which can cause a significant delay in diagnosis and treatment. However, for this outbreak, the use of the BioFire® system allowed for immediate testing of specimens in Camp Arifjan. As a result of this outbreak, the theater medical command learned the value of the rapid nucleic acid detection system and acquired additional systems for hospitals and traveling PM teams throughout the theater.

PM assets of the medical brigade, namely the theater PM physician and the commander of the PM detachment, advised the medical brigade commander to recommend to the installation commander the 3 major actions that resulted in control of the norovirus outbreak. Those actions were 1) the halting of flights in and out of Camp Arifjan; 2) the isolation of infected, symptomatic patients and the quarantine of recovering and exposed service members; and 3) the restriction of movement of service members to prevent spread of infection to others outside the quarantine area.

At the time of the Camp Arifjan outbreak, an additional outbreak thought to be due to norovirus occurred in a classified country, where 13 soldiers were identified with symptoms consistent with norovirus. On 27 May, a PM surveillance laboratory team and the theater PM physician were forward deployed to determine the root cause of that outbreak. A link between the 2 outbreaks could not be proven.

Given the number of service members located at Camp Arifjan at the time and the high attack rate of norovirus, the case count could have been in the thousands. Despite the successful response, this outbreak highlighted the need for a theater outbreak response plan, which should include details on responding to infectious patients in the deployed environment and frequent education and review of proper cleaning techniques and personal hygiene. This outbreak also demonstrated the importance of inclusion of the medical brigade PM teams for any outbreak investigations in theater. The epidemic curve suggests this was a point source epidemic, originating from the index case and then further spreading via person-to-person contact and contaminated environmental surfaces, including latrines. Because of the efforts of the public health teams, the outbreak response was successful in limiting the breadth and duration of the outbreak.

Author Affiliations: Army Satellite of Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Defense Health Agency (Ms. Kebisek, Dr. Ambrose); 223rd Medical Detachment, Preventive Medicine (MAJ Richards); 223rd Medical Detachment, Microbiology (MAJ Hourihan); 75th Combat Support Hospital Detachment, Public Health Nursing (CPT Buckelew); Theater Preventive Medicine Physician, TF 1st MED (COL Finder)

References

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Gastrointestinal infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2002–2012. MSMR. 2013;20(10):7–11.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance snapshot: Norovirus outbreaks among military forces, 2008–2016. MSMR. 2017;24(7):30.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Historical perspective: Norovirus gastroenteritis outbreaks in military forces. MSMR. 2011;18(11):7–8.Darling ND, Poss DE, Brooks KM, et al.

- Brief report: Laboratory characterization of noroviruses identified in specimens from Military Health System beneficiaries during an outbreak in Germany, 2016–2017. MSMR. 2017;24(7):2–29.

- Kasper MR, Lescano AG, Lucas C, et al. Diarrhea outbreak during U.S. military training in El Salvador. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(7).

- Putnam SD, Sanders JW, Frenck RW, et al. Self-reported description of diarrhea among military populations in Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom. J Travel Med. 2006;13(2):92–99.

- Riddle MS, Martin GJ, Murray CK, et al. Management of acute diarrheal illness during redeployment: a deployment health guideline and expert panel report. Mil Med. 2017;182(9):34–52.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Updated norovirus outbreak management and disease prevention guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2011;4(60):1–18.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Norovirus. https://www.cdc.gov/norovirus/about/index.html. Accessed 3 June 2019.

- Ambrose J, Kebisek J, Gibson K, White D. Gaps in reportable medical event surveillance across the Department of Defense and recommended tools to improve surveillance practices. MSMR. 2019. In press.