Abstract

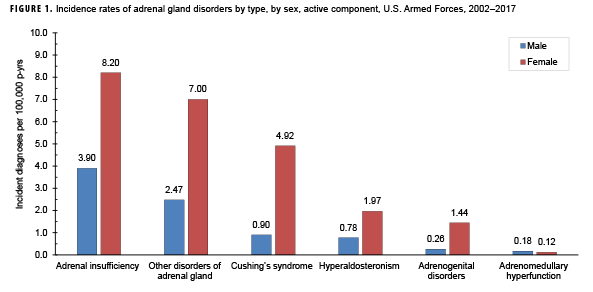

During 2002–2017, the most common incident adrenal gland disorder among male and female service members was adrenal insufficiency and the least common was adrenomedullary hyperfunction. Adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed among 267 females (crude overall incidence rate: 8.2 cases per 100,000 person-years [p-yrs]) and 729 males (3.9 per 100,000 p-yrs). In both sexes, overall rates of other disorders of adrenal gland and Cushing's syndrome were lower than for adrenal insufficiency but higher than for hyperaldosteronism, adrenogenital disorders, and adrenomedullary hyperfunction. Crude overall rates of adrenal gland disorders among females tended to be higher than those of males, with female:male rate ratios ranging from 2.1 for adrenal insufficiency to 5.5 for androgenital disorders and Cushing's syndrome. The highest overall rates of adrenal insufficiency for males and females were among non-Hispanic white service members. Among females, rates of Cushing's syndrome and other disorders of adrenal gland were higher among non-Hispanic white service members compared with those in other race/ethnicity groups. In both sexes, the annual rates of adrenal insufficiency and other disorders of adrenal gland increased slightly during the 16-year period.

What Are the New Findings?

This is the first MSMR report of the incidence of adrenal disorders in the U.S. Armed Forces. These relatively rare disorders were diagnosed in service members 2,356 times during 2002–2017 (rate: 10.7 cases per 100,000 person-years). Rates increased with age, especially over age 30. The most common type of adrenal disorder was adrenal insufficiency.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Because of the relative rarity of these disorders in young adults, their impact on force readiness is limited; however, their occurrence may impair affected individuals' readiness and ability to continue to serve. The causes of these disorders are unknown so there are no force health protection measures that can be implemented.

Background

The adrenal glands are located at the top of each kidney and produce hormones that help regulate metabolism, blood sodium and potassium levels, blood pressure, response to stressors, immune function, and other essential functions.1 The adrenal glands produce cortisol, aldosterone, catecholamines (epinephrine, norepinephrine, and dopamine), and small amounts of androgens (hormones with testosterone-like function).1

Adrenal disorders can be caused by the production of too much or too little of a particular adrenal hormone.1 Adrenal insufficiency occurs when the outer portion of the adrenal gland (adrenal cortex) does not produce an adequate amount of cortisol.2 This condition is due to either primary adrenal failure (Addison’s disease) or to secondary hypothalamic-pituitary impairment; the former is most often the result of autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex and the latter is generally the result of pituitary disease.2,3 A diagnosis of primary adrenal insufficiency is established on the basis of a poor response to the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) stimulation test and an elevated blood ACTH level.4 Adrenal insufficiency is rare with prevalence estimates in Western countries ranging from 82 to 280 cases per million population.3–12 Individuals affected by this condition may experience fatigue, generalized weakness, loss of appetite, abdominal pain, weight loss, low blood pressure, and salt craving.3 Both primary and secondary adrenal insufficiency occur more frequently in adult women than in adult men and can be life threatening if untreated.5,6,13–15 Primary adrenal insufficiency most often appears between the ages of 30 and 50 years while the age at diagnosis of secondary adrenal insufficiency peaks in the sixth decade of life.5,14

Cushing's syndrome is a rare disorder caused by chronic exposure to excess cortisol and can be caused by the administration of excessive doses of corticosteroids (exogenous) or the overproduction of cortisol by the adrenal cortex (endogenous).16 As a screening test for Cushing's syndrome, the Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice guidelines recommend a single test with a high diagnostic accuracy (an overnight 1-mg dexamethasone suppression test, an elevated late night salivary cortisol level, or an elevated free cortisol level in a 24-hour urine specimen).17 In the U.S., among commercially insured patients under 65 years of age, endogenous Cushing's syndrome has an estimated incidence of between 39.5 and 48.6 cases per million population per year.18 Common signs and symptoms of Cushing's syndrome include decreased libido, weight gain/obesity, plethora, facial rounding, menstrual changes, hirsutism (male-pattern hair growth on a woman's face, chest and back), hypertension, depression, lethargy, and abnormal glucose tolerance.16 In general, women are more likely than men to develop Cushing's syndrome; however, both the sex and age-related distributions vary by the cause of the condition.16,19,20 Cushing's syndrome is associated with considerable comorbidity and increased mortality.21 Cardiometabolic (e.g., thromboembolism, hypertension, diabetes, dyslipidemia) and neuropsychiatric comorbidities (e.g., mood disorders) are common as are adverse effects on bone (e.g., decreased osteoblastic and increased osteoclastic activity).22,23

Hyperaldosteronism is a rare condition that occurs when the adrenal cortex produces too much aldosterone, a hormone that controls blood pressure by regulating blood sodium and potassium levels.1 The excess aldosterone is produced either by a tumor in one or both of the adrenal glands (primary aldosteronism—usually a noncancerous adenoma) or by some other condition elsewhere in the body (secondary aldosteronism—e.g., renovascular disease).1,24 Hyperaldosteronism is associated with the development of adverse cardiometabolic and renal effects that are partly independent of its effects on blood pressure.24,25 Among high-risk groups of hypertensive patients and those with hypokalemia (low blood potassium level), the Endocrine Society's Clinical Practice guidelines recommend screening for primary hyperaldosteronism using the plasma aldosterone/renin ratio.26 Studies that have investigated the prevalence of primary hyperaldosteronism report a wide range of estimates (<1%–30%) that vary depending on the characteristics of the study population, health care setting, and diagnostic method employed.27 Hyperaldosteronism occurs more frequently in women than in men with the condition most commonly presenting between the ages of 30 and 50 years.28

Andrenogenital disorders are caused by overproduction of adrenocortical steroids (especially those with androgenic or estrogenic effects) and are characterized by masculinization of women, feminization of men, sexual ambiguity, or precocious sexual development of children.1 This condition may be the result of congenital enzyme defects in steroidgenesis (congenital adrenal hyperplasia) or may be acquired, developing as a result of a tumor or hyperplasia of the adrenal glands.29 The incidence of congenital adrenal hyperplasia varies according to ethnicity and geographic region. In the U.S., this condition is particularly common in American Indians and Yupik Eskimos (1 in 280 live births).30 Among U.S. non-Hispanic whites, the incidence has been estimated at 1 in 15,000 live births.31

Adrenomedullary hyperfunction is a rare condition that occurs when the inner portion of the adrenal gland (medulla) produces an excess of catecholamines, hormones important for the regulation of metabolism, contractility of cardiac and smooth muscle, and neurotransmission.32 Common symptoms of adrenomedullary hyperfunction include hypertension, episodic headache, excessive sweating, and tachycardia.33 This condition is most often due to rare neoplasms called pheochromocytoma.32 The estimated incidence of pheochromocytoma is 0.8 cases per 100,000 person-years.33 Diagnosis of this condition is typically made between the ages of 40 and 50 years without pronounced predominance in either sex.33

The incidence and prevalence of adrenal disorders in the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces have not been previously described. The current report addresses this gap by examining the incidence, prevalence, and trends of adrenal disorders other than adrenal cancer among the population of active component U.S. service members during 2002–2017.

Methods

The surveillance period was Jan. 1, 2002 through Dec. 31, 2017. The surveillance population consisted of all individuals who served in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. Adrenal gland disorders were identified by diagnostic codes for "disorders of adrenal gland" recorded in standardized records of inpatient and outpatient encounters in military and nonmilitary medical facilities documented in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) (Table 1). The diagnostic codes were grouped into six types of adrenal gland disorders: Cushing's syndrome, hyperaldosteronism, adrenogenital disorders, adrenal insufficiency, adrenomedullary hyperfunction, and other disorders of adrenal gland.

An incident case was defined by hospitalization with a case-defining diagnostic code in any diagnostic position or two or more outpatient diagnoses of the same adrenal disorder type between 1 and 180 days apart, with at least one of these diagnoses in a primary diagnostic position. One incident case diagnosis per individual per adrenal disorder type was counted. As such, a service member could be counted as a case for multiple different adrenal disorder types during the surveillance period. Individuals who met the case definition for a specific adrenal gland disorder prior to the surveillance period (i.e., prevalent cases) were excluded from the incidence rate calculation of that disorder. Incidence rates were calculated as incident adrenal gland disorder diagnoses per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) of active component service. Both deployed and non-deployed person-time was used in the denominator. Among incident cases of adrenal gland disorders, the numbers of individuals with prior diagnoses of adrenal gland cancer (ICD-9, 194.0, 237.2 ICD-10: C74.*, D44.1*) and each of the five other adrenal gland disorder types were ascertained.

Lifetime prevalence of the diagnoses of each of the six adrenal disorder types was estimated for each year in the 16-year surveillance period. The numerator for annual lifetime prevalence calculations consisted of service members who had ever been diagnosed with a particular adrenal gland disorder and who were in service during the given calendar year. The denominator for annual prevalence calculations consisted of the total number of active component service members who served at any time during the given year. Annual prevalence estimates were calculated as the number of prevalent cases per 100,000 active component service members.

Results

From 2002 through 2017, the most common incident adrenal gland disorder among male and female service members was adrenal insufficiency and the least common was adrenomedullary hyperfunction (Table 2; Figure 1). Adrenal insufficiency was diagnosed among 267 females (crude overall incidence rate: 8.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs) and 729 males (crude overall incidence rate: 3.9 cases per 100,000 p-yrs) during this period (Table 2). Among both male and female service members, crude overall incidence rates of other disorders of adrenal gland and Cushing's syndrome were lower than for adrenal insufficiency but higher than for hyperaldosteronism, adrenogenital disorders, and adrenomedullary hyperfunction.

Of the service members diagnosed with other disorders of adrenal gland, 10.1% (n=23) of females and 6.7% (n=31) of males had been previously diagnosed with adrenal insufficiency. In addition, 5.3% (n=12) of female service members with incident diagnoses of other disorders of adrenal gland had prior diagnoses of Cushing's syndrome (data not shown). Of the service members diagnosed with adrenomedullary hyperfunction, 15.2% (n=5) of males and 50.0% (n=2) of females had been previously diagnosed with other disorders of adrenal gland. Furthermore, 12.1% (n=4) of male service members who were diagnosed with adrenomedullary hyperfunction had been previously diagnosed with adrenal gland cancer.

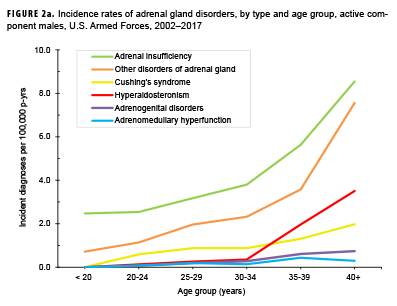

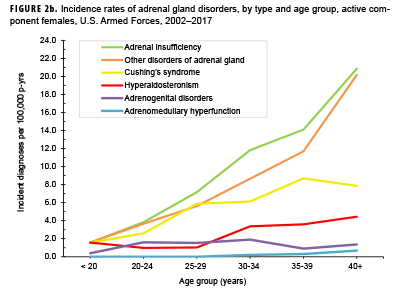

Crude overall incidence rates of adrenal gland disorders among females tended to be higher than those of males, with female:male rate ratios ranging from 2.1 for adrenal insufficiency to 5.5 for adrenogenital disorders and Cushing's syndrome (Table 2). Adrenomedullary hyperfunction was the only condition for which males and females had a similar incidence (0.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs for males and 0.1 cases per 100,000 p-yrs for females). Among service members of both sexes, overall rates of adrenal insufficiency and other disorders of adrenal gland increased approximately exponentially with increasing age; the greatest differences in overall incidence rates were between those aged 35–39 years and those aged 40 years or older (Figures 2a, 2b; Table 3). Among males, rates of Cushing's syndrome increased monotonically with age. A similar pattern in rates of this condition was observed among females for all but the oldest age group (40+ years) (Table 3). Rates of hyperaldosteronism were relatively low among members of the youngest age groups for both sexes. However, among females, the greatest difference in incidence rates of this condition were observed between those aged 25–29 years and those aged 30–34 years whereas the greatest difference in rates among males was between those aged 30–34 years and those aged 35 years or older (Figures 2a, 2b; Table 3). Rates of andrenogenital disorders among female service members were highest among those in the age groups spanning 20–34 years. In contrast, rates of this condition among male service members increased approximately linearly with increasing age. Across all age groups among both sexes, rates of adrenomedullary hyperfunction were relatively low.

Descriptive analysis of age at incident case diagnosis by sex showed that, for Cushing's syndrome, other disorders of adrenal gland, and hyperaldosteronism, the median ages at incident case diagnoses were two to 7 years higher among males than females (data not shown). The median age at incident diagnosis of adrenogenital disorders was 10 years higher among males than females. In contrast, the median age at incident diagnosis of adrenomeduallary hyperfunction was 5.5 years higher among females than among males (data not shown). During the surveillance period, the highest overall incidence rates of adrenal insufficiency for males and females were among non-Hispanic white service members (Table 3). Among both sexes, rates of hyperaldosteronism were highest among non-Hispanic black service members. Among females, rates of Cushing's syndrome and other disorders of adrenal gland were higher among non-Hispanic white service members compared with those in other race/ethnicity groups. Rates of other disorders of adrenal gland among male service members were highest among those of other/unknown race/ethnicity (Table 3).

Overall incidence rates of adrenal insufficiency and Cushing's syndrome were higher among service members in the Air Force compared with members of other service branches whereas rates of other disorders of adrenal gland were highest among Army members (Table 2). Across all adrenal disorder types, overall incidence rates were lowest among Marine Corps members. With the exception of adrenogenital disorders and adrenomedullary hyperfunction, rates were higher among senior officers, compared to those in other grades. Service members in health care occupations had the highest overall incidence rates of all adrenal gland disorders except adrenomedullary hyperfunction (Table 2).

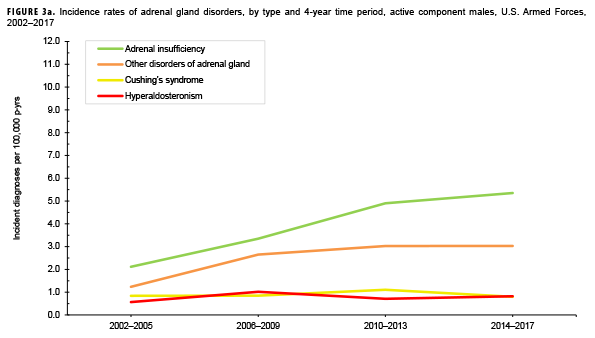

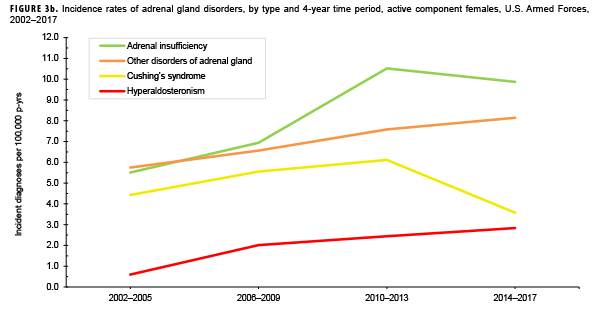

Due to the small number of cases each year, incidence rates were collapsed into 4-year groupings to assess changes over time. During the 16-year surveillance period, the incidence of Cushing's syndrome and hyperaldosteronism among males remained relatively low and stable (Figure 3a). Notably, the incidence of adrenal insufficiency among males increased from a low of 2.1 cases per 100,000 p-yrs during the 2002–2005 period to a high of 5.4 cases per 100,000 p-yrs during the 2014–2017 period. Annual rates of other disorders of adrenal gland among males increased from a low of 1.2 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in the 2002–2005 period to a peak of 3.0 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in the 2010-2013 and 2014-2017 periods. Among females, the incidence of adrenal insufficiency and Cushing's syndrome peaked during the 2010–2013 period at 10.5 and 6.1 cases per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively (Figure 3b). In contrast, rates of hyperaldosteronism and other disorders of the adrenal gland increased gradually during the surveillance period. The number of cases for adrenomedullary hyperfunction and adrenogenital disorders were too small to assess trends over time.

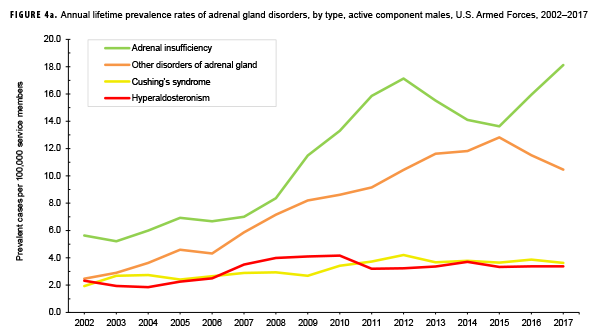

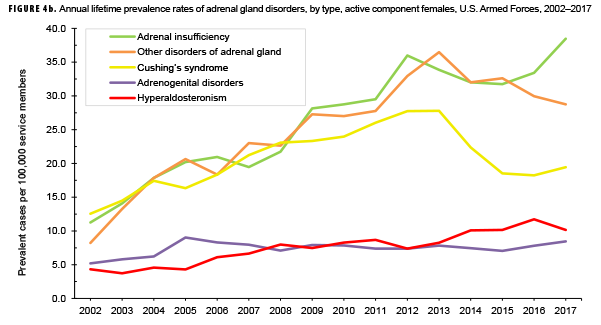

The pattern of annual prevalence rates of adrenal insufficiency during 2002–2017 were broadly similar for both sexes with an increase in prevalence between 2002 and 2012. This increase was followed by a slight decrease until 2015, after which rates increased through the end of the surveillance period (Figures 4a, 4b). For males, annual prevalence of other disorders of adrenal gland increased steadily during 2002–2015 and then decreased during the last two years of the surveillance period. Prevalence of this condition among females showed a similar pattern but with a peak occurring in 2013. Annual prevalence of Cushing's syndrome and hyperaldosteronism among males was relatively stable throughout the 16-year period. In contrast, prevalence of these two conditions among females showed an overall increase during the period. Among females, prevalence of adrenogenital disorders increased slightly during 2002–2017.

Editorial Comment

Adrenal disorders are rare conditions but when present can significantly reduce the operational fitness of affected military members. As such, current adrenal dysfunction or any history of adrenal dysfunction requiring treatment or hormone replacement, is a disqualifying condition for entrance into the U.S. military.34 However, because the majority of adrenal disorders generally are diagnosed among those over 30 years of age, newly incident diagnoses of these conditions are likely to affect service members later in their military careers. Conditions requiring referral to a medical evaluation board include adrenal insufficiency requiring replacement therapy, Cushing's syndrome, primary hyperaldosteronism when resulting in uncontrolled hypertension and/or hypokalemia, pheochromocytoma, and salt-wasting congenital adrenal hyperplasia.35

The incidence and prevalence of the adrenal disorders of interest have not been well characterized, particularly in the U.S. general population. Consistent with findings from studies of adrenal disorders in the general populations of other Western countries,6,14,17,26 results of the current study showed that the incidence and prevalence of the types of adrenal disorders considered here, with the exception of adrenomedullary hyperfunction, occur more frequently in females than in males. The finding that the highest overall incidence rates of all adrenal disorders except adrenomedullary hyperfunction were observed among service members in health care occupations is likely due to heightened medical awareness, easier access to care, and, perhaps, older age compared to their respective counterparts in other occupations. The pattern of higher rates of adrenal disorders (with the exception of adrenogenital disorders and adrenomedullary hyperfunction) observed among senior officers compared to those in other grades is likely highly associated with and confounded by age. In addition, the finding that overall rates of all adrenal disorder types were lowest among Marine Corps members may be related to differences in the age distributions of the services.

Data on trends in incidence and prevalence of adrenal disorders in the general U.S. population during a comparable time period were not available at the time of this report, thus precluding comparisons to the current results. Because the current analysis did not assess rates ofscreening for adrenal disorders, it is unclear if, or to what degree, changes in screening practices may have factored into any of the temporal patterns in incidence reported here. Current recommendations for screening and clinical practice guidelines for all adrenal disorders are available from the Endocrine Society at: https://www.endocrine.org/guidelines-and-clinical-practice/ clinical-practice-guidelines/.

One important limitation of the current analysis is that the incidence rates of adrenal disorders were based on diagnoses recorded on standardized medical records. Given this, the findings reflect the rates of adrenal functional abnormalities that were clinically detected; subclinical dysfunction was not included as not all service members are tested for adrenal disorders. An additional limitation of the current analysis is related to the implementation of MHS GENESIS, the new electronic health record for the Military Health System. During 2017, medical data from sites that were using MHS GENESIS were not available in DMSS. These sites include Madigan Army Medical Center, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, Naval Hospital Bremerton, and Naval Hospital Oak Harbor. Consequently, medical encounters and person-time data for individuals who received care at these facilities during 2017 were not included in the analysis. Despite these limitations, findings from this report make a useful contribution to the literature on the overall incidence of adrenal disorders among a demographically diverse population and provide new information regarding temporal changes in the incidence of these conditions by sex.

References

- Else T, Hammer GD, McPhee SJ. Disorders of the Adrenal Cortex. In: McPhee SJ, Hammer GD, eds. Pathophysiology of Disease: An Introduction to Clinical Medicine. 7th ed. 2014. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

- Arlt W, Allolio B. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet. 2003;361(9372):1881–1893.

- Charmandari E, Nicolaides NC, Chrousos GP. Adrenal insufficiency. Lancet Seminar. 2014;383(9935):2152–2167.

- Bornstein SR, Allolio B, Arlt W, et al. Diagnosis and Treatment of Primary Adrenal Insufficiency: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(2):364–389.

- Kong MF, Jeffcoate W. Eighty-six cases of Addison’s disease. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1994;41(6):757–761.

- Laureti S, Vecchi L, Santeusanio F, Falorni A. Is the prevalence of Addison's disease underestimated? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1999; 84(5):1762.

- Lovas K, Husebye ES. High prevalence and increasing incidence of Addison's disease in western Norway. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;56(6):787–791.

- Erichsen MM, Lovas K, Skinningsrud B, et al. Clinical, immunological, and genetic features of autoimmune primary adrenal insufficiency: observations from a Norwegian registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(12):4882–4890.

- Meyer G, Neumann K, Badenhoop K, Linder R. Increasing prevalence of Addison's disease in German females: health insurance data 2008–2012. Eur J Endocrin. 2014;170(3):367–373.

- Olafsson AS, Sigurjonsdottir HA. Increasing prevalence of Addison disease: results from a nationwide study. Endocrin Pract. 2016;22(1):30–35.

- Regal M, Paramo C, Sierra SM, Garcia-Mayor RV. Prevalence and incidence of hypopituitarism in an adult Caucasian population in northwestern Spain. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2001;55:735–740.

- Tomlinson JW, Holden N, Hills RK, et al, for the West Midlands Prospective Hypopituitary Study Group. Association between premature mortality and hypopituitarism. Lancet 2001;357:425–431.

- Bates AS, Van’t Hoff W, Jones PJ, Clayton RN. The effect of hypopituitarism on life expectancy. J Clin Endocrinol Meta.b 1996; 81: 1169–72.

- Nilsson B, Gustavasson-Kadaka E, Bengtsson BA, Jonsson B. Pituitary adenomas in Sweden between 1958 and 1991: incidence, survival, and mortality. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2000;85:1420–25.

- Tomlinson JW, Holden N, Hills RK, et al. Association between premature mortality and hypopituitarism. Lancet. 2001;357:425–31.

- Sharma ST, Nieman LK, Feelders RA. Cushing's syndrome: epidemiology and developments in disease management. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:281–289.

- Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. The diagnosis of Cushing's Syndrome: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93(5):1526–1540.

- Broder MS, Neary MP, Chang E, Cherepanov D, Ludlan WH. Incidence of Cushing’s syndrome and Cushing's disease in commercially insured patients <65 years old in the United States. Pituitary. 2015;18(3):283–289.

- Newell-Price J, Bertagna X, Grossman AB, Nieman LK. Cushing's syndrome. Lancet. 2006;367:1605–1617.

- Clayton RN, Raskauskiene D, Reulen RC, Jones PW. Mortality and morbidity in Cushing’s disease over 50 years in Stokeon-Trent, UK: audit and meta-analysis of literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(3):632–642.

- Graversen D, Vestergaard P, Stochholm K, Gravholt CH, Jørgensen JO. Mortality in Cushing's syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(3):278–282.

- Clayton RN, Jones PW, Reulen RC, et al. Mortality in patients with Cushing's disease more than 10 years after remission: a multicentre, multinational, retrospective cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2016;4(7):569–576.

- Javanmard P, Duan D, Geer EB. Mortality in patients with endogenous Cushing's syndrome. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2018;47(2):313–333.

- Monticone S. Burrello J, Tizzani D, et al. Prevalence and clinical manifestations of primary aldosteronism encountered in primary care practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;69(14)1811–1820.

- Milliez P, Girerd X, Plouin PF, Blacher J, Safar ME, Mourad JJ. Evidence of an increased rate of cardiovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(8):1243–1248.

- Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, et al. The Management of Primary Aldosteronism: Case Detection, Diagnosis, and Treatment: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016;101(5):1889–1916.

- Kayser SC, Dekkers T, Groenewoud HJ, et al. Study heterogeneity and estimation of prevalence of primary aldosteronism: a systematic review and meta-regression analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2016; 101(7): 2826–2835.

- Mulatero P, Stowasser M, Loh KC, et al. Increased diagnosis of primary aldosteronism, including surgically correctable forms, in centers from five continents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004; 89:1045.

- El-Maouche D, Arlt DP. Congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Lancet Seminar. 2017;390:2194–2210.

- Pang S, Murphey W, Levine LS, et al. A pilot newborn screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia in Alaska. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1982;55:413.

- Therrell BL. Newborn screening for congenital adrenal hyperplasia. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2001;30:15.

- Else T, Hammer GD, McPhee SJ. Disorders of the Adrenal Medulla. In: McPhee SJ, Hammer GD, eds. Pathophysiology of Disease: An Introduction to Clinical Medicine. 7th ed. 2014. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Education; 2014.

- Fung MM, Viveros OH, O’Connor DT. Diseases of the adrenal medulla. Acta Physiol (Oxf). 2008;192(2):325-335.

- Department of Defense. Instruction 6130.03, Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction into the Military Services. Change 1. 30 March 2018. http://www.esd. whs.mil/Portals/54/Documents/DD/issuances/ dodi/613003p.pdf. Accessed on 27 Sept. 2018.

- U.S. Department of the Army. Army Regulation 40–501: Standards of Medical Fitness, 14 June 2017. U.S. Department of the Army, Washington, D.C. https://armypubs.army. mil/ProductMaps/PubForm/Details.aspx?PUB_ ID=1002549. Accessed on 26 Nov. 2018