What Are the New Findings?

The crude rate of incident inguinal hernia diagnoses between 2010 and 2019 among U.S. active component service members was 34.3 per 10,000 person-years, with a modest decline over the surveillance period. Among the 44,898 incident inguinal hernia diagnoses, 22,349 were followed by an open or laparoscopic repair and among these, 6,276 (28.1%) had a pain diagnosis within 1 year.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

For service members, inguinal hernias can result in reduced operational readiness due to lost duty time or medical evacuation from theater. Persistent pain from hernia repair surgeries can interfere with job duties and requirements for meeting standards of physical fitness. This study identifies subgroups of service members at higher risk for inguinal hernia and subsequent pain diagnosis.

Abtract

An inguinal hernia occurs when an internal organ protrudes through a tear or weak spot in the abdominal muscles. Among U.S. military service members, inguinal hernia is the fourth most prevalent digestive condition in terms of individuals affected and number of medical encounters. This study found that the overall incidence of inguinal hernia diagnoses between 2010 and 2019 among U.S. active component service members was 34.3 per 10,000 person-years. Older service members, males, non-Hispanic whites, and those in combat-specific occupations had comparatively higher incidence rates. Among the 44,898 incident inguinal hernia diagnoses during the surveillance period, 22,349 were followed by an open or laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair procedure. Of these, 12,210 (54.6%) were open and 10,139 (45.4%) were laparoscopic. Among the 22,349 inguinal hernia repair procedures, 6,276 (28.1%) were followed by pain diagnoses within 1 year after the repair procedures. Although the incidence of inguinal hernia diagnoses among active component service members decreased modestly during the surveil ace period, the rate of hernia repair peaked in 2013, and the frequency of diagnoses of pain following hernia repair increased between 2010 and 2019.

Background

An inguinal hernia occurs when an internal organ, usually part of the small intestine, protrudes into the inguinal canal through a tear or weak spot in the abdominal muscles. Inguinal hernias usually present as a lump in the groin that goes away with mild pressure or while lying down.1 They can have many acquired causes, such as increased pressure on the abdomen due to strenuous activity, pregnancy, obesity, and chronic coughing or sneezing. Additional risk factors include being male, white, older, having a family history of inguinal hernia, and having a previous inguinal hernia or hernia repair (such as in childhood).2

Among U.S. military service members, inguinal hernia is the fourth most prevalent digestive condition in terms of individuals affected and number of medical encounters, exceeded in frequency only by diagnoses of esophageal disease, other gastroenteritis and colitis, and constipation.3 In 2019, there were 10,853 encounters for inguinal hernia among 4,568 affected service members.3 Inguinal hernias can also affect military readiness, particularly when they result in evacuations from theaters of operations. Among male service members, inguinal hernia was the second most common reason for medical evacuation from the Central Command Area of Responsibility (CENTCOM AOR) in 2019 (n=31).4 The incidence of inguinal hernia among active component service members between 2005 and 2014 was 33.8 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs), with rates being higher among males, non-Hispanic whites, older personnel, and those in combat-specific occupations.5

Inguinal hernia repair is one of the most common operations performed in the U.S., with more than 800,000 repairs done annually.6 Options for surgical repair include open or laparoscopic repair. Open mesh repair is the preferred repair technique for primary inguinal hernia because it is reproducible by nonspecialist surgeons and is less likely to lead to recurrence, but primary suture repair can be performed when mesh is contraindicated.1,6 Compared to open repair, laparoscopic repair is associated with longer operation times but less severe postoperative pain, fewer complications, and quicker return to normal physical activities.6

Pain persisting beyond the first few days following hernia repair is the primary complication of inguinal hernia repair and is reported in 3–39% of patients.6–11 The relatively wide range of estimates for occurrence of pain following hernia repair can be attributed to the variation in patient populations studied, the severity of pain reported, and the time elapsed since hernia repair. In addition, there are varying definitions of chronic pain following hernia repair. Recent guidelines for prevention and management of postoperative pain following hernia repair recommend that chronic pain be defined as pain lasting at least 6 months after operation, as some patients may improve substantially between 3 and 6 months postoperation.8,12 Chronic, disabling pain beyond 1 year is believed to occur in a small percentage of patients (<1%).7 In hernia repairs, chronic pain can be caused by nerve injuries sustained during the surgery, inflammation, ischemia, or neuropathy; however, the true cause is often multifactorial and difficult to distinguish in a given patient.6–8 Chronic pain has also been previously associated with high levels of preoperative pain, younger age, an anterior surgical approach, and a postoperative complication.1

The objective of this study was to examine the incidence of inguinal hernia diagnoses, the incidence of open and laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair procedures, and the proportion and rate of pain diagnoses (including both acute and chronic pain) following inguinal hernia repair, among active component service members between 2010 and 2019.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2010 through 31 Dec. 2019. The surveillance population included all active component service members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps who served at any time during the surveillance period. Records of inpatient and outpatient encounters documented in the Defense Medical Surveillance System were used to ascertain cases of inguinal hernia, inguinal hernia repair procedures, and pain diagnoses.

An incident case of inguinal hernia was defined by having an inguinal hernia diagnosis (International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision [ICD-9]: 550.*; 10th revision [ICD-10]: K40.*) in any diagnostic position of an inpatient or outpatient encounter. A service member could be counted only once per lifetime and the incident date was the date of the first qualifying encounter. Incident cases that occurred before the start of the surveillance period were excluded. For the purpose of measuring the incidence of inguinal hernia diagnoses, person-time was censored at the time of the incident inguinal hernia diagnosis, when the service member left service, or at the end of the surveillance period (whichever came first). Incidence rates were calculated per 10,000 p-yrs.

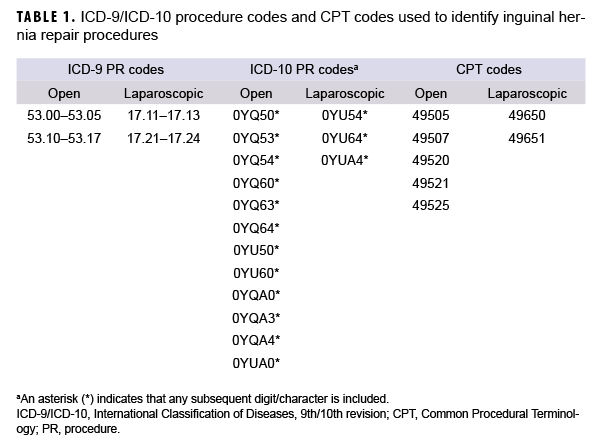

The incidence of inguinal hernia repair procedures was measured among the incident inguinal hernia cases identified during the surveillance period. Open and laparoscopic hernia repair procedures were defined by the presence of an inpatient or outpatient encounter with a qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 procedure code, or Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code, in any procedural position (Table 1). The first occurring repair procedure recorded on or after the incident inguinal hernia diagnosis was selected and an individual could be counted as having a repair procedure only once during the surveillance period. For the purpose of measuring incidence of inguinal hernia repair procedures, the person-time began to accrue at the time of the incident inguinal hernia diagnosis, and was censored at the time of the first inguinal hernia repair procedure, when the service member left service, or at the end of the surveillance period (whichever came first). Repair rates were calculated per 100 p-yrs.

The occurrence of post-procedural inguinal hernia repair pain was measured in the year following the first inguinal hernia repair procedure using ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnoses for postoperative pain, abdominal pain, testicular pain, and mononeuritis of the lower limb (Table 2). These ICD-9 and ICD10 codes were selected in consultation with DOD pain medicine physicians, and were based on codes that would be most likely to represent the diagnosis of inguinal pain after hernia surgery. The first inpatient or outpatient encounter with a qualifying pain diagnosis in any diagnostic position, occurring within 1 year after the inguinal hernia repair procedure, was selected. For the purpose of measuring rates of pain diagnoses following inguinal hernia repair procedures, the person-time began to accrue at the time of the incident inguinal hernia repair procedure, and was censored at the time of the first pain diagnosis, when the service member left service, or at the end of the surveillance period (whichever came first). Rates of pain diagnoses were calculated per 100 p-yrs.

Covariates included age group, sex, race/ethnicity group, service branch, rank/grade, and military occupation. A prior pain diagnosis was defined by having an inpatient or outpatient encounter with a pain diagnosis (Table 2) in any diagnostic position on or before the inguinal hernia repair procedure.

Results

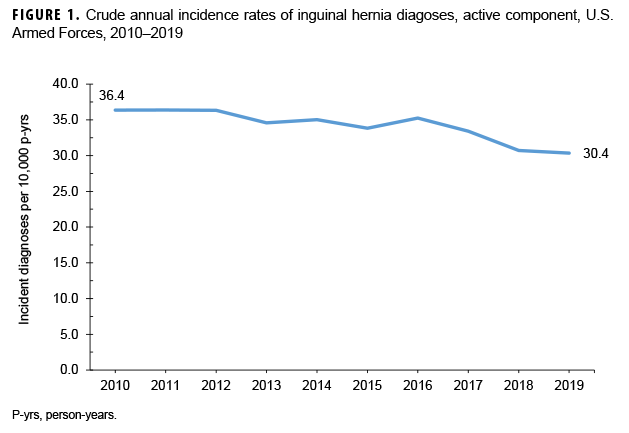

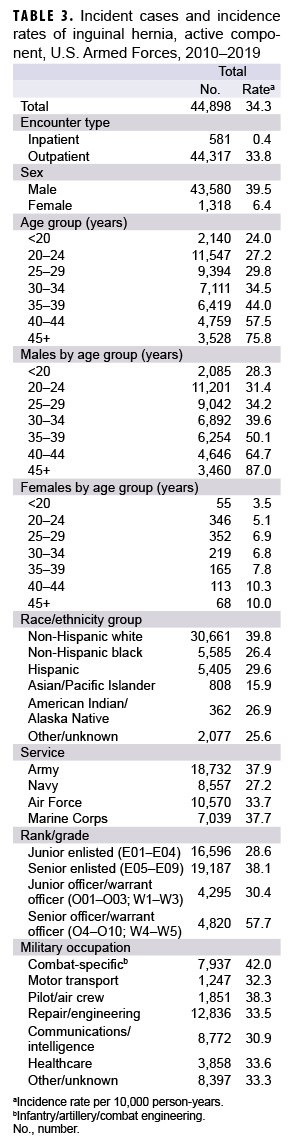

During 2010–2019, the crude overall incidence of inguinal hernia diagnoses among active component service members was 34.3 per 10,000 p-yrs (Table 3). Compared to their respective counterparts, males (39.5 per 10,000 p-yrs), nonHispanic whites (39.8 per 10,000 p-yrs), senior officers (57.7 per 10,000 p-yrs), and those in combat-specific occupations (42.0 per 10,000 p-yrs) had higher overall rates. Overall rates of incident inguinal hernia diagnoses increased with increasing age, with service members aged 45 years or older having more than 3 times the rate of those less than 20 years of age. Crude annual incidence rates of inguinal hernia diagnoses decreased slightly over the course of the 10-year surveillance period, from 36.4 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2010 to 30.4 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2019 (Figure 1).

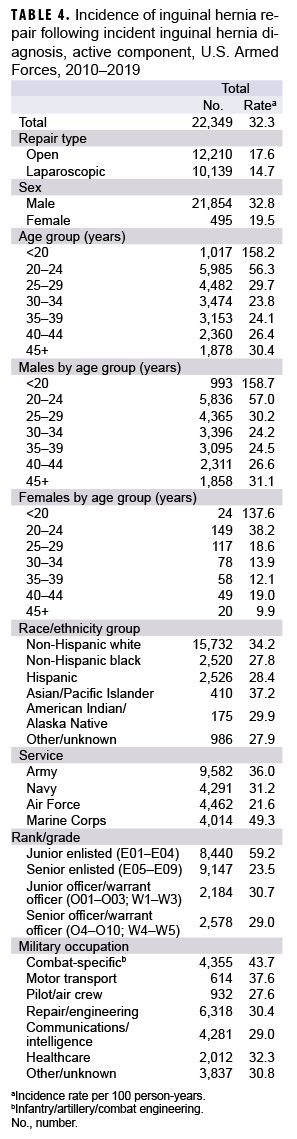

Among the 44,898 incident inguinal hernia diagnoses during the surveillance period, 22,349 were followed by open or laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair procedures (Table 4). Of these, 12,210 (54.6%) were open and 10,139 (45.4%) were laparoscopic. The proportion of incident inguinal hernia diagnoses with subsequent laparoscopic repairs increased annually over the course of the surveillance period, from 11.5% in 2010 to 28.4% in 2019 (data not shown). In contrast, the proportion treated by open repairs peaked in 2013 at 32.5% and then decreased to 21.6% by 2019 (data not shown). The overall incidence rate of repair among those with incident inguinal hernia diagnoses during the surveillance period, was 32.3 per 100 p-yrs (Table 4). Compared to their respective counterparts, males (32.8 per 100 p-yrs), service members less than 20 years of age (158.2 per 100 p-yrs), non-Hispanic whites (34.2 per 100 p-yrs), Marine Corps members (49.3 per 100 p-yrs), junior enlisted personnel (59.2 per 100 p-yrs), and service members in combat-specific occupations (43.7 per 100 p-yrs) had higher overall rates of hernia repair.

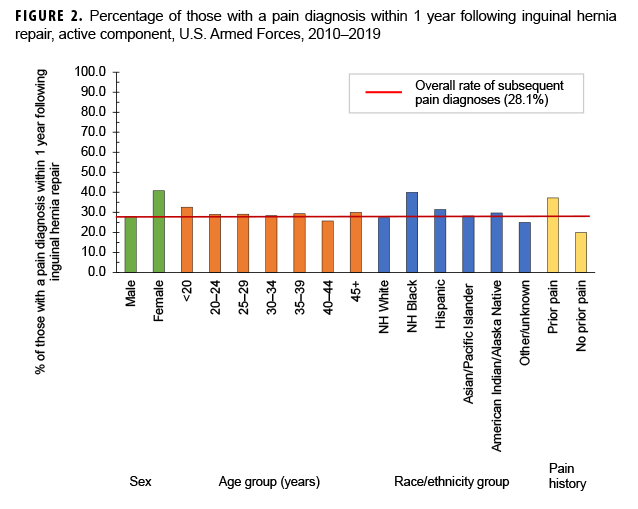

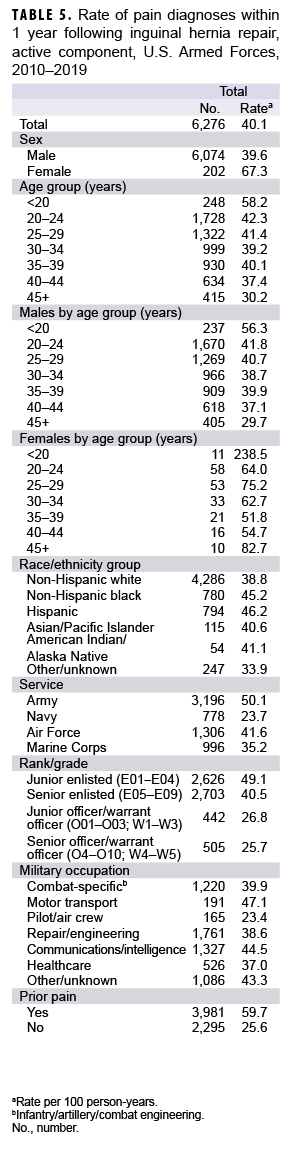

Among the 22,349 inguinal hernia repair procedures, 6,276 (28.1%) were followed by pain diagnoses within 1 year after the repair procedures (Table 5, Figure 2). The proportions with pain diagnoses in the year following surgery were similar for those with laparoscopic (27.5%) and open (28.6%) repair procedures (data not shown). The proportion with a pain diagnosis in the year following surgery increased from 17.1% in 2010 to 31.5% in 2019 among males and from 25.0% in 2010 to 52.6% in 2019 among females (data not shown). Overall, the percentages of inguinal hernia repairs with pain diagnoses in the following year were highest during the last 3 years of the surveillance period and ranged from 31.8% in 2017 to 32.3% in 2018 (data not shown). Among those with an inguinal hernia repair procedure, the overall rate of pain in the subsequent year was 40.1 per 100 p-yrs (Table 5).

Compared to their respective counterparts, females (67.3 per 100 p-yrs), service members less than 20 years of age (58.2 per 100 p-yrs), Hispanics (46.2 per 100 p-yrs), Army members (50.1 per 100 p-yrs), enlisted personnel (junior 49.1 per 100 p-yrs; senior 40.5 per 100 p-yrs), and those with a prior pain diagnosis (59.7 per 100 p-yrs) had higher overall rates of pain diagnoses. Among those with a pain diagnosis in the year following hernia repair, 30.7% (n=2,975) had a pain diagnosis within the first 3 months, 27.4% (n=2,658) had a diagnosis within 3-6 months after, 22.8% (n=2,214) within 6-9 months after, and 19.1% (n=1,855) had a pain diagnosis within 9-12 months following repair (data not shown). Abdominal pain was the most frequently diagnosed type of pain, which occurred among 85.3% (n=5,352) of those with any pain diagnosis, followed by acute postoperative pain (19.5%, n=1,224), testicular pain (17.2%, n=1,079), chronic postoperative pain (7.5%, n=471), pelvic pain (3.8%, n=240), and mononeuritis (3.3%, n=209) (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

This study found that the overall incidence rate of inguinal hernia diagnoses among active component service members was 34.3 per 10,000 p-yrs between 2010 and 2019. In addition, older service members, males, non-Hispanic whites, and those in combat-specific occupations had comparatively higher rates of incident inguinal hernia diagnoses. These patterns are consistent with previously identified risk factors in the civilian population and are also similar to findings from a prior MSMR report.2,5 Service members with pre-existing abdominal hernias would be screened and precluded from joining military service; however, results of this analysis indicate that a sizable proportion of service members develop hernias while in uniform. Of interest is the positive association between combat-specific occupations and incidence of inguinal hernia, which suggests that strenuous physical activity or traumatic injury could play a role in increasing risk among younger service members, although this could not be confirmed using the available data.

In addition, this study found that while the crude annual incidence rates of inguinal hernia diagnoses among active component service members decreased modestly during the surveillance period, the rate of hernia repair peaked in 2013, and the rates of pain following hernia repair increased between 2010 and 2019. The proportion of inguinal hernias treated by subsequent laparoscopic repair increased from 11.5% in 2010 to 28.4% in 2019. In contrast, the proportion treated by open repair peaked in 2013 at 32.5% and then decreased to 21.6% by 2019. This pattern of change is not surprising given that the laparoscopic technique has grown in popularity in the U.S., with estimates ranging from 16.8% to 41.0% of all inguinal hernia operations.13However, this did not correlate with decreased pain outcomes, as the percentages of inguinal hernia repairs with pain diagnoses in the following year were highest during the last 3 years of the surveillance period, ranging from 31.6% in 2017 to 32.2% in 2018, and the overall proportions of laparoscopic and open procedures with pain diagnoses in the following year were roughly similar (27.5% and 28.6%, respectively).

During the 10-year surveillance period, open repair remained the most common procedure type overall, and was performed at a rate of 17.6 per 100 p-yrs following inguinal hernia diagnosis, compared to 14.7 per 100 p-yrs for laparoscopic repair. However, by 2019, a greater proportion of inguinal hernias were being treated by laparascopy (28.4%) than by open repair (21.6%). Males, younger personnel, and those in combat specific occupations were more likely than their respective counterparts to have repair procedures following incident inguinal hernia diagnoses. The reasons for these findings are unclear but may be related to the severity of the incident hernia. It is also possible that the nature of a service member's duties may precipitate the decision to undergo hernia repair.

For service members, persistent pain can interfere with job duties and requirements for meeting standards of physical fitness. This study indicated that pain following inguinal hernia repair was more common among women, younger personnel, and those with prior abdominal or groin pain diagnoses. These results are consistent with findings from international surveys of self-reported pain following hernia surgery.11,14 Pain persisting after hernia repair can be treated using physical therapy, pharmacological analgesics, injections with local anesthetics, sensory stimulation or ablation of nerves, and surgery.1,6,8 Anti-inflammatory agents are recommended as the first line of treatment, and if these are unsuccessful then nerve blocks (injection of anesthetic on or near the nerve/pain receptor) can be used.6 When these treatments have failed, then neurectomy may be necessary.6

There are several limitations to this study. The primary limitation was that pain was ascertained using ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes for post-operative pain, abdominal pain, testicular pain, and mononeuritis. The lack of a specific ICD diagnosis code for post-inguinal herniorrhaphy pain likely led to the capture of incidents of pain unrelated to the hernia repair procedure; however, the surveillance period was restricted to the year following hernia repair in order to reduce the likelihood of this occurring. A further limitation to this approach is that pain persisting for longer than 1 year following hernia repair could not be assessed, as it was more likely that these pain diagnoses could be related to other conditions or procedures aside from hernia repair. In addition, data were not available for lost duty time or disability due to pain following hernia or hernia repair. Hernia diagnoses, repair procedures, and pain diagnoses occurring in deployed settings were not assessed. However, it is expected that most hernia repairs occurring as a result of inguinal hernia sustained during deployment would be captured since service members would likely be medically evacuated out of theater for this procedure. Procedures and diagnoses that occurred after a service member left service, or were paid for out of pocket, were also not captured.

For service members, inguinal hernias can result in reduced operational readiness, and persistent pain from hernia repair surgeries can interfere with job duties and physical fitness requirements. Service members at higher risk for pain following hernia repair, such as female service members, younger personnel, those with prior abdominal or groin pain diagnoses, and those with prior repair procedures, should be monitored and treated according to best practice guidelines if the pain does not subside.8

Acknowledgment: The authors thank CAPT Eric Stedje-Larsen, MD, Program Director, Pain Medicine, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, for providing ICD codes to identify pain following hernia repair.

References

- Jenkins JT, O'Dwyer PJ. Clinical review: Inguinal hernias. BMJ. 2008;336(7638):269–272.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. Inguinal hernia. Mayo Clinic. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/ inguinal-hernia/symptoms-causes/syc-20351547. Accessed 9 August 2020.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2019. MSMR. 2020;27(5):2–9.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Medical evacuations out of U.S. Central Command, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2019. MSMR. 2020;27(5):27–32.

- O’Donnell FL, Taubman SB. Incidence of abdominal hernias in service members, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005–2014. MSMR. 2016;23(8):2–10.

- Hammoud M and Gerken J. Inguinal hernia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan. 2020 Apr 27.

- Condon RE. Groin pain after hernia repair. Ann Surg. 2001;233(1):8.

- Andresen K and Rosenberg J. Management of chronic pain after hernia repair. J Pain Res. 2018; 11:675–681.

- Poobalan AS, Bruce J, King PM, et al. Chronic pain and quality of life following open inguinal hernia repair. BJS. 2001;88(8):1122–1126.

- Courtney CA, Duffy K, Serpell MG, and O’Dwyer PJ. Outcome of patients with severe chronic pain following repair of groin hernia. BJS. 2002;89(10):1310–1314.

- Bay-Nielsen M, Perkins FM, and Kehlet H. Pain and functional impairment 1 year after inguinal herniorrhaphy: a nationwide questionnaire study. Ann Surg. 2001; 233(1):1–7.

- Alfieri S, Amid PK, Campanelli G, et al. International guidelines for prevention and management of post-operative chronic pain following inguinal hernia surgery. Hernia. 2011;15(3):239–249.

- Reiner MA and Bresnahan ER. Laparoscopic total extraperitoneal hernia repair outcomes. JSLS. 2016;20(3):e2016.00043.

- Franneby U, Sandblom G, Nordin P, Nyren O, and Gunnarsson U. Risk factors for long-term pain after hernia surgery. Ann Surg. 2006;244(2):212–219.