What Are the New Findings?

The majority of new military accessions in 2014 with documented ADHD diagnoses within their first year of service were not detected during their MEPS screening physical exam (64.8%), suggesting many new accessions do not disclose previous ADHD diagnoses during enlistment. New accessions in 2014 with ADHD diagnoses who received a prescription for ADHD medication started medication quickly (91.0% within 6 months) and had higher rates of attrition from service and higher incidence rates of comorbid mental health disorders than their untreated ADHD counterparts.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Due to its high prevalence in the U.S. general population, ADHD impacts the pool of military applicants. Future changes to enlistment standards should consider how to optimize or incentivize applicant disclosure of a pre-existing ADHD diagnosis during MEPS screening or service specific medical waiver review and discourage withholding an ADHD diagnosis during enlistment.

Abstract

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common childhood diagnosis and affects the pool of potential military applicants. Early detection and treatment of ADHD may decrease the risk of developing comorbidities; however, accession policy in place during this study period (2014–2018) disqualified applicants who used ADHD medication for more than 24 months cumulative after age 14. The objective of this study was to assess attrition from military service in newly accessed active component service members diagnosed with ADHD as compared to controls. In addition, attrition rates and incidence rates of mental health diagnoses were assessed in service members with ADHD by treatment status (i.e., treated vs untreated ADHD) where treatment was defined as being dispensed an FDA-approved ADHD medication at least twice within 181 days. Almost two-thirds (64.8%) of newly accessed ADHD cases in 2014 were identified after enlistment medical screening at Military Entrance Processing Stations (MEPS) (i.e., post-MEPS). These post-MEPS ADHD cases accounted for 99.1% of the treated ADHD cases. The vast majority of treated cases (91.0%) were dispensed ADHD medication within 6 months of accession. The treated ADHD group had higher rates of attrition and incidence of mental health disorders during the follow-up period. These study findings highlight the problem of nondisclosure of ADHD among military applicants. Future changes to enlistment standards should consider the optimal way to promote applicant disclosure of ADHD during MEPS screening or for medical waiver review and should discourage withholding an ADHD diagnosis during enlistment.

Background

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a common diagnosis in childhood, characterized by persistent impairing inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. Symptoms are usually recognized in patients before the age of 12.1 Estimates for the prevalence of ADHD in U.S. children 2–17 years old range from 9–11% while adult ADHD prevalence in the U.S. is estimated at 4.4%.2 Medication has become a mainstay of treatment with U.S. surveillance data indicating that 62% of children with ADHD in 2016 took medication.3 ADHD patients frequently have comorbid conditions such as mood, anxiety, and substance use disorders,2,4–6 but early ADHD treatment with medication may convey some protection against these co-occurring conditions.7–9

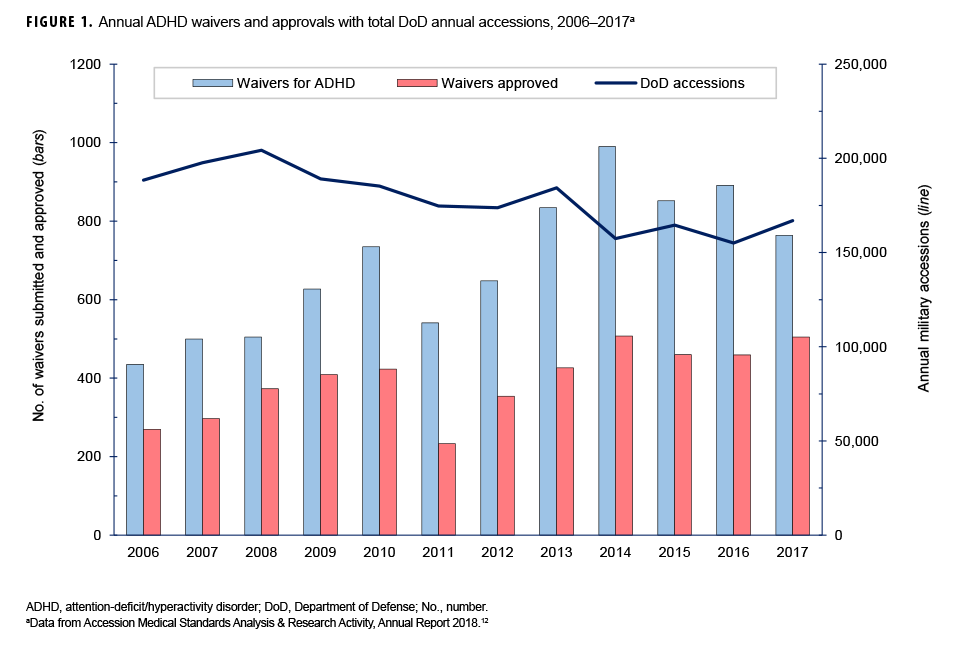

Due to its high prevalence in the adolescent and adult population, ADHD has readiness and force health impacts on the Department of Defense (DOD) and affects the pool of military applicants.7 During 2000–2018, the prevalence rate of ADHD in the DOD ranged between 1.7% and 3.9% and has steadily declined since 2011 (E. T.Reeves, MD, unpublished data, 2017). Current DOD accession policy, DOD Instruction (DODI) 6130.03 (updated in 2018), disqualifies military applicants with diagnosed ADHD if they meet any of the following conditions: 1) had ADHD medication prescribed in the previous 24 months; 2) had an educational plan or work accommodation after 14 years of age; 3) had a history of comorbid mental health disorders; 4) had documentation of adverse academic, occupational, or work performance.10 The previous updates to DOD accession policy occurred in 2010 and 2005 and disqualified applicants who used ADHD medication for more than 24 months cumulative after the age of 14 years and if there had been medication use in the previous 12 months, respectively.11 The policy change trends have extended the time period that ADHD-diagnosed accessions to the military had to be without prescribed ADHD medication. Comparing annual rates in 2006–2010 to 2011–2017, this policy change was associated with increased waiver submissions for ADHD (mean of 560/year vs 789/year) and percent applicant disqualifications (36.4%/ year vs 46.9%/year) (Figure 1).12 In 2017, ADHD and disruptive behavior disorders were the fifth most frequent diagnoses resulting in medical disqualification of first-time enlisted active component military applicants (this study's surveillance period was from Jan. 2014 through Dec. 2018).12 A previous study evaluated ADHD accessions through waiver admissions to the Army and found no change in retention rates; however, that study was conducted well before the current accession policy was in place.7 Other studies have assessed ADHD and its association with PTSD,4,6 but no surveillance data have been published on new accession active component service members with ADHD and the effect of medication treatment.

The current study provides evidence-based data relevant to the DOD's medical accession policy. The main objective of this study was to assess attrition from military service in active component service members diagnosed with ADHD compared to matched controls without ADHD. In addition, attrition rates were assessed for service members with ADHD by treatment status. Finally, incidence rates of selected mental health disorder diagnoses were compared between service members with ADHD who were prescribed medication for ADHD and those who were not.

Methods

This study utilized a retrospective cohort design. The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2014 through 31 Dec. 2018. The surveillance population included any member of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps who first entered military service in 2014. All data used to identify prevalent cases of ADHD were derived from records routinely maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which is maintained by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD). The DMSS includes medical encounter data (e.g. outpatient visits, hospitalizations) of active component members of the U.S. Armed Forces in military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System) treatment facilities. The DMSS also includes medical screening data from Military Entrance Processing stations (MEPS) and records of prescribed and dispensed medications from the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) which were also used in this analysis.

For surveillance purposes, an ADHD case was defined as a service member with a qualifying ADHD diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position for diagnoses assigned during a MEPS medical screening; or 1 hospitalization with any of the qualifying diagnoses of ADHD in the first or second diagnostic position; or 2 outpatient medical encounters within 180 days of each other, with any of the defining diagnoses of ADHD in the specialty care setting, identified by Medical Expense and Performance Reporting System (MEPRS) code beginning with 'BF'. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9) and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) codes used to identify ADHD cases included all those falling under the parent codes 314 and F90, respectively. Because the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) requires the presence of symptoms prior to age 12 to meet the diagnostic criteria for ADHD, individuals with a diagnosis of ADHD in 2014 were considered to be prevalent cases that existed at the time of accession regardless of when they were formally diagnosed.1

All active component service members who entered military service in 2014 and were found to have ADHD diagnoses during a MEPS medical screening or who met the case definition for a new ADHD diagnosis during 2014 were identified. Service members within this cohort were then further classified into 2 groups: ADHD cases that were treated with ADHD medication and ADHD cases who were not treated with ADHD medication.

To qualify as treated, service members had to have pharmacy documentation of being dispensed an FDA licensed drug for the treatment of ADHD at least twice within 6 months (181 days); this criterion is consistent with that employed in previous studies of ADHD medication use.9 Qualifying ADHD medications included stimulants (amphetamines, methylphenidates), guanfacine (Intuniv), clonidine (Kapvay), and atomoxetine (Strattera). Active component service members dispensed ADHD medication with longer gaps than this threshold were classified as untreated. Because a service member could be admitted to the cohort at any time in 2014, pharmacy data through the first 180 days of 2015 were included in the analysis.

The control group consisted of active component service members without ADHD and matched 1:1 (i.e., case control ratio was 1:1) on age, gender, and date of accession (within 30 days of each ADHD case). Exclusion criteria included a diagnosis of depression, anxiety, or substance-related disorder at accession as documented in the MEPS record or a documented ADHD diagnosis prior to 2014.

The follow-up period for each cohort member and his or her matched control began at 181 days after their initial entry date into service. To assess attrition from service, individuals in each group were followed until 31 Dec. 2018 or until the service member left active service or died. To determine the incidence of mental health disorders, service members were followed until 31 Dec. 2018 or until the service member left active service, died, or received 1 or more of the mental health diagnoses of interest as defined below. To assess attrition, length of service was calculated by summing the number of days a service member was in service.

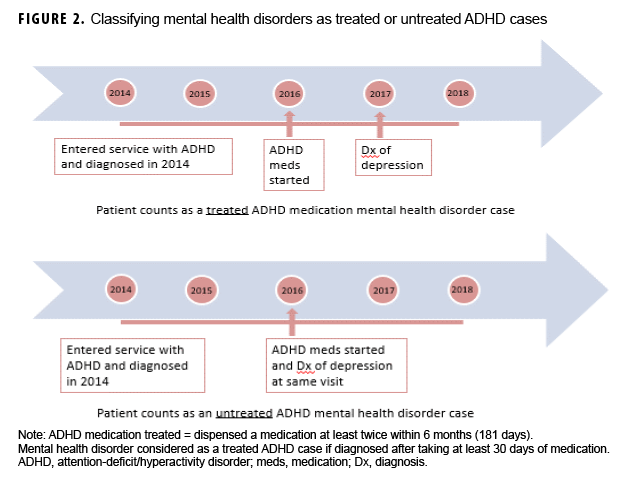

Occurrences of depressive, anxiety, alcohol- and/or substance-related disorders were ascertained by applying standard AFHSD case definitions.13 Depressive, anxiety, alcohol- or substance-related disorders were all respectively defined as 1 hospitalization with any of the defining diagnoses (see AFHSD case definitions for full ICD-9 and ICD-10 code lists for each disorder) in the first or second diagnostic position; or 2 outpatient medical encounters, within 180 days of each other, with any of the defining diagnoses in the first or second diagnostic position; or 1 outpatient medical encounter in a psychiatric or mental health care specialty setting, defined by MEPRS code 'BF', with any of the defining diagnoses in the first or second diagnostic position. Service members who received a qualifying mental health disorder diagnosis were associated with the treated ADHD group only if the service member had been dispensed ADHD medication at least 30 days prior to the diagnosis of depressive, anxiety, alcohol- or substance-related disorder (Figure 2).

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize service members in the 3 groups (control without ADHD, ADHD only, and ADHD with medication) who entered the military and were newly diagnosed with ADHD in 2014. The groups were compared on several background variables (i.e., sex, age group, race/ethnicity group, branch of service, and rank/grade) using chi-square tests. To compare the incidence of depressive, anxiety, alcohol- and substance-related disorders diagnosed in these groups, crude incidence rates and their associated 95% confidence intervals were calculated. Finally, Kaplan-Meier curves and the log-rank test were used to examine attrition rates in the study groups over time. All analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

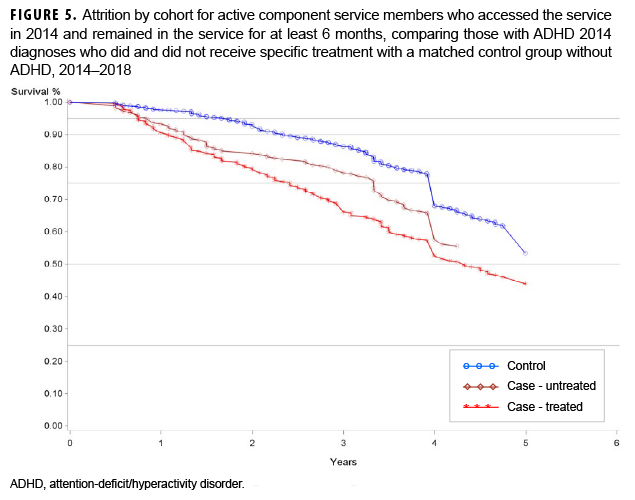

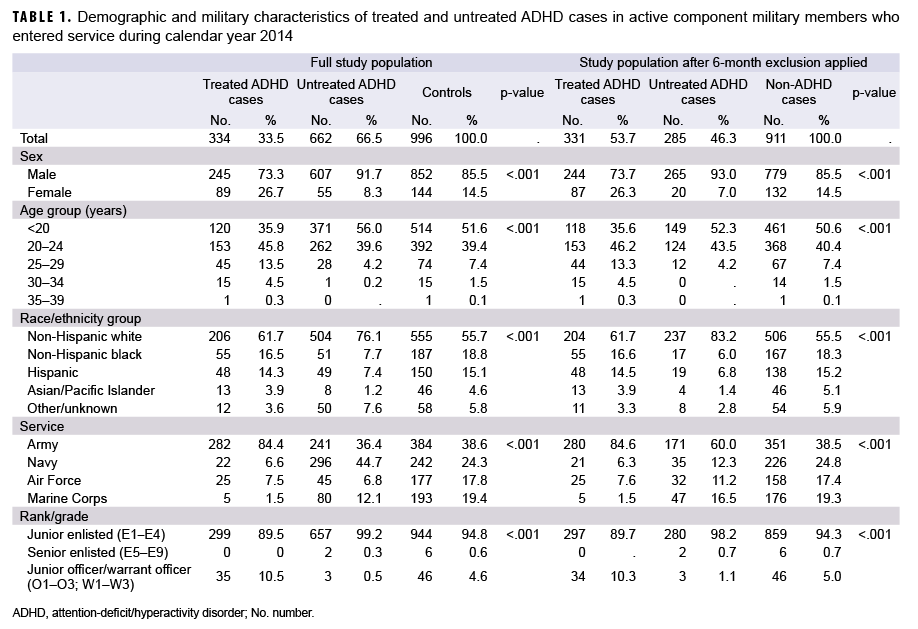

A total of 996 service members who were newly accessed into the military in 2014 and qualified as an ADHD case were identified. Of the ADHD cases identified, 334 were classified as treated with ADHD medication and 662 were classified as untreated. Compared to the untreated ADHD group, the treated group had relatively higher proportions of females, service members aged 20 years or older, members of racial/ethnic minority groups, Army members, and junior officers. The untreated ADHD group had relatively higher proportions of Navy, Marine Corps, and Air Force members compared to the treated ADHD group (Table 1).

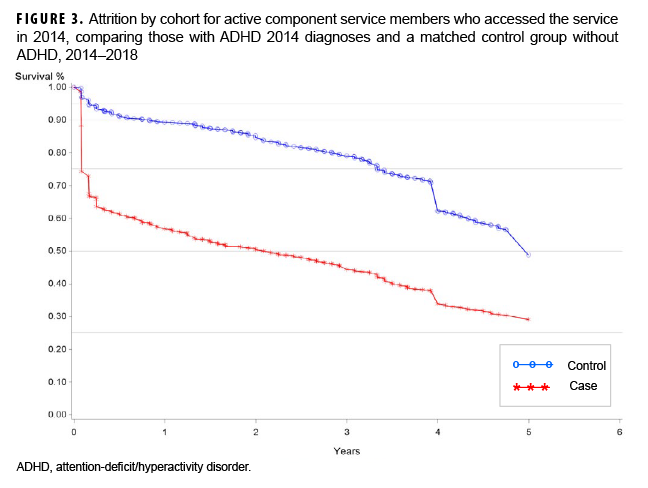

The initial attrition rates in the total ADHD cohort (treated and untreated ADHD groups) and the control group are illustrated in Figure 3. Nearly 40% of ADHD cases left service within the first 6 months of the surveillance period. Since these individuals left the military in less than 6 months, they did not have the opportunity to be a treated ADHD case as defined in this study (dispensed medication at least twice within 6 months). Thus, an additional exclusion was applied for people who did not remain in the military for at least 6 months.

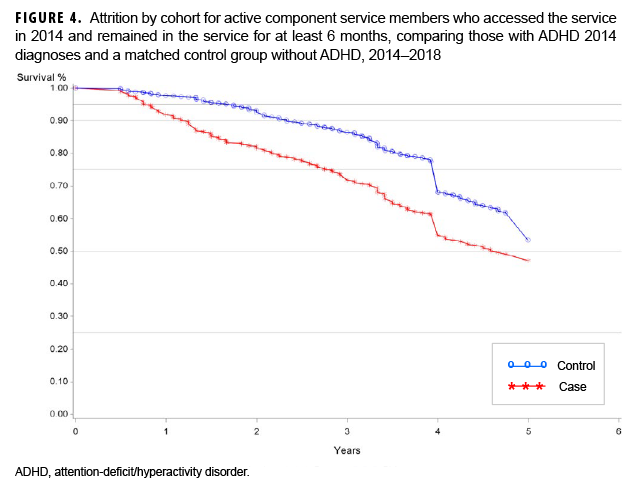

After applying the requirement that service members remained in the military at least 6 months, the ADHD group decreased to 616 individuals (331 treated with medication and 285 untreated), and the non-ADHD (control) group decreased to 911 (Table 1). The relative proportions within the covariates remained similar with the exception of the proportion of untreated service members in the Navy which decreased from 53% (n=296) to 12% (n=35) (Table 1). Although the large initial drop of service members did not remain after applying the requirement for at least 6-months of service, attrition curves comparing ADHD (combined treated and untreated) and non-ADHD groups and treated ADHD, untreated ADHD, and non-ADHD groups were clearly different. The treated ADHD cohort had the highest attrition rates among these groups (Figures 4, 5).

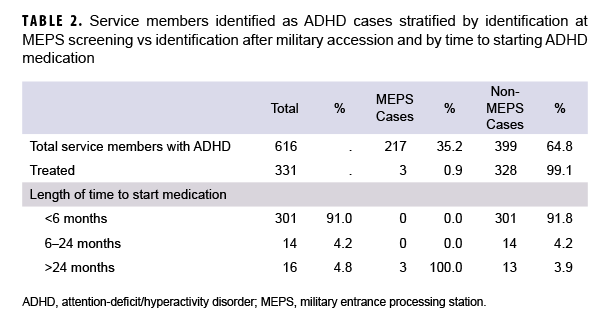

ADHD cases were analyzed according to whether they were detected during MEPS screening encounters or after accession (non-MEPS encounter) (Table 2). Only 35.2% of the ADHD cases were identified with MEPS screening. Almost all of the treated ADHD cohort (328 of 331) were first documented after MEPS, and 91.0% of treated ADHD cases started medication within 6 months of accession. The 3 ADHD cases who were identified during MEPS screening and who went on to start medication during the surveillance period were first dispensed medication over 2 years after accession.

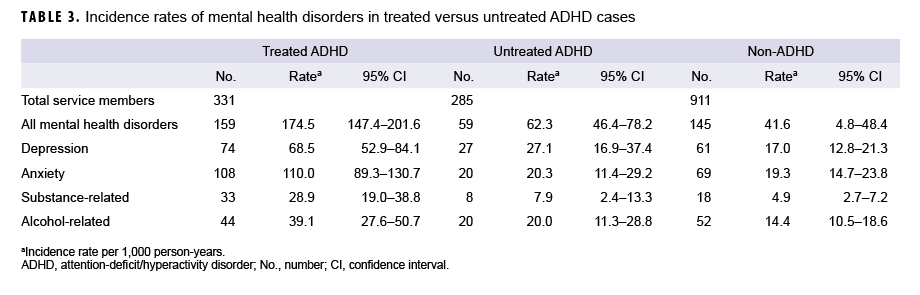

Compared to untreated ADHD and non-ADHD groups, the treated ADHD group had significantly higher crude incidence rates of all mental health disorders with the highest rate observed for anxiety disorders (an individual service member could have had multiple mental health disorders). The untreated ADHD cohort's incidence rates of mental health disorders were not statistically significantly different from the rates among those in the non-ADHD group (Table 3).

Editorial Comment

This report describes accessions to the military in 2014 with documented ADHD in the same year to examine the impact of the military ADHD enlistment standards in place at that time. Nearly two-thirds of the new accession ADHD cases detected in the first year of service in 2014 were identified after accession and after the MEPS screening process. Service members with treated ADHD (99.1% of whom were diagnosed after the MEPS screening process) started medications quickly with 91.0% having had drugs prescribed within 6 months of accession. This finding suggests that most treated ADHD cases identified in this study withheld their ADHD diagnosis at accession and then quickly sought treatment after completing basic training. The treated ADHD group had the highest attrition rates over the 5-year surveillance period compared to untreated ADHD and non-ADHD groups and had crude higher incidence rates of mental health disorders.

The ADHD accession policy selects less severe and higher functioning ADHD individuals, but nondisclosure of medical conditions, particularly behavioral health diagnoses, is a difficult problem for accession medical screening to resolve. Previous studies have discussed the problem that more recruits are dismissed annually for withholding an ADHD diagnosis than applicants who are truthful in disclosing the diagnosis.7 Results of the current study suggest the persistence of this problem, even after multiple policy changes over the past 2 decades. Future changes to enlistment standards should consider how to optimize or incentivize applicant disclosure of ADHD during MEPS screening or for medical waiver review as well as discourage withholding an ADHD diagnosis during enlistment. Potential ways to encourage disclosing ADHD in military applicants could involve different ADHD standards based on a new accession's occupation (difficult to do with MEPS screening as an occupation may not be defined at that time) or emphasizing more relaxed standards with service-based medical waivers after a thorough review and interview with the enlistee. At the same time, nondisclosure of ADHD should be descentivised with the threat of disqualification from service or other punishment. Additional studies examining ADHD's impact on military readiness, deployment health, and different occupations would help advance and inform accession decisions regarding future ADHD standards.

This is the first study to assess medication dispensed for ADHD in new active component accessions since ADHD enlistment standards were updated in 2010. In addition, this study uses multiple sources of data available in the DMSS which allow for a longitudinal analysis and provide analytic evidence that may inform accession policies in the future.

Multiple limitations to this study should be considered. This analysis used data from PDTS which identified whether ADHD medications had been dispensed to active component service members with ADHD diagnoses. However, these data cannot be used to assess the medication adherence of these patients. Furthermore, patients with ADHD in this study could be prescribed ADHD medications for other medical conditions (FDA-approved indications or off-label use) or obtain ADHD medications by other means without a prescription. In addition, the population of patients who were dispensed ADHD medication could be different (e.g., have more severe symptoms or comorbid conditions) from the population of ADHD patients who were not dispensed medication. ADHD diagnosis data were derived from ICD-9 and ICD-10 coded medical encounters or from the MEPS tables according to standardized health surveillance case definitions which could underestimate the prevalence of ADHD, especially in service members not actively being treated with medication for ADHD or withholding information at MEPS assessment (misclassification bias).

The DOD must continue to evaluate its accession policies related to ADHD, since the condition impacts the military enlistment pool. The observation of potentially undisclosed ADHD cases with worse outcomes in this study illustrates problems and challenges for the military when recruits do not truthfully reveal a previous ADHD diagnosis. Additional studies could further explore the issues identified in this analysis related to ADHD in new accessions and contribute to the enhanced readiness of service members with ADHD.

Author Affiliations: Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland (Maj Sayers); Defense Health Agency, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (Ms. Zhu, Dr. Clark).

Disclaimer: The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Attention-deficit and disruptive behavior disorders. In: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Data and Statistics About ADHD. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/adhd/data.html. Accessed 5 Sept. 2019.

- Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, Holbrook JR, Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among US children and adolescents, 2016. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):199–212.

- Howlett JR, Campbell-Sills L, Jain S, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and risk of posttraumatic stress and related disorders: A prospective longitudinal evaluation in US Army soldiers. J Trauma Stress. 2018;31(6):909–918.

- Spencer AE, Faraone SV, Bogucki OE, et al. Examining the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016; 77(1):72–83.

- Ivanov I, Yehuda R. Optimizing fitness for duty and post-combat clinical services for military personnel and combat veterans with ADHD—a

- Krauss MR, Russell RK, Powers TE, Li L. Accession standards for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a survival analysis of military recruits, 1995–2000. Mil Med. 2006;171(2):99–102.

- Biederman J, DiSalvo M, Fried R, Woodworth KY, Biederman I, Faraone SV. Quantifying the protective effects of stimulants on functional outcomes in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A focus on number needed to treat statistic and sex effects. J Adolesc Health. 2019;65(6):784–789.

- Chang Z, D’Onofrio BM, Quinn PD, Lichtenstein P, Larsson H. Medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(12):916–922.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03. Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services. 6 May 2018.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03. Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services. 28 April 2010.

- Department of Defense. Accession Medical Standards Analysis & Research Activity, Annual Report 2018. Silver Spring, MD: Statistics and Epidemiology Branch, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research; 2018.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Epidemiology-and-Analysis/Surveillance-Case-Definitions. Accessed 6 Sept. 2019.