What Are the new Findings?

The 501 incident cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis in 2020 represented an unadjusted annual incidence rate of 37.8 cases per 100,000 p-yrs among active component service members, the lowest of the 5-year surveillance period of 2016–2020. Among demographic and service sub-groups, rates were higher among males, those under 20 years old, non-Hispanic Black service members, and recruit trainees.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Exertional rhabdomyolysis is a serious illness associated with physically demanding activities, particularly in hot weather. Prevention of this condition is linked to the prevention of the other heat-related illnesses. Such illnesses are a perennial threat to the health and readiness of the force and demand continuing attention to preventive measures by leaders and service members.

Abstract

Among active component service members in 2020, there were 501 incident cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis, for an unadjusted incidence rate of 37.8 cases per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs). Subgroup-specific rates in 2020 were highest among males, those less than 20 years old, non-Hispanic Black service members, Marine Corps or Army members, and those in combat specific occupations. During 2016–2020, crude rates of exertional rhabdomyolysis reached a peak of 42.9 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2018 after which the rate decreased to a low of 37.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020. Most cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis were diagnosed at installations that support basic combat/ recruit training or major ground combat units of the Army or the Marine Corps. Medical care providers should consider exertional rhabdomyolysis in the differential diagnosis when service members (particularly recruits) present with muscular pain or swelling, limited range of motion, or the excretion of darkened urine after strenuous physical activity, especially in hot, humid weather.

Background

Rhabdomyolysis is characterized by the breakdown of skeletal muscle cells and the subsequent release of intracellular muscle contents into the circulation. The characteristic triad of rhabdomyolysis includes weakness, myalgias, and red to brown urine (due to myoglobinuria) accompanied by an elevated serum concentration of creatine kinase.1,2 In exertional rhabdomyolysis, damage to skeletal muscle is generally caused by high-intensity, protracted, or repetitive physical activity, usually after engaging in unaccustomed strenuous exercise (especially with eccentric and/or muscle-lengthening contractions).3 Even athletes who are used to intense training and who are being carefully monitored are at risk of this condition,4 especially if new overexertion-inducing exercises are being introduced.5 Illness severity ranges from elevated serum muscle enzyme levels without clinical symptoms to life-threatening disease associated with extreme enzyme elevations, electrolyte imbalances, acute kidney failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, compartment syndrome, arrhythmia, and liver dysfunction.1–3,6 A diagnosis of exertional rhabdomyolysis should be made when there are severe muscle symptoms (e.g., pain, stiffness, and/or weakness) and laboratory results indicating myonecrosis (usually defined as a serum creatine kinase level 5 or more times the upper limit of normal) in the context of recent exercise.7

Risk factors for exertional rhabdomyolysis include exertion in hot, humid conditions; younger age; male sex; a lower level of physical fitness; a prior heat illness; impaired sweating; and a lower level of education.1,3,8–11 Acute kidney injury, due to an excessive concentration of free myoglobin in the urine accompanied by volume depletion, renal tubular obstruction, and renal ischemia, represents a serious complication of rhabdomyolysis.6,12 Severely affected patients can also develop compartment syndrome, fever, dysrhythmias, metabolic acidosis, and altered mental status.11

In U.S. military members, rhabdomyolysis is a significant threat during physical exertion, particularly under heat stress.8,10,13 Moreover, although rhabdomyolysis can affect any service member, new recruits, who are not yet accustomed to the physical exertion required of basic training, may be at particular risk.10 Each year, the MSMR summarizes the numbers, rates, trends, risk factors, and locations of occurrences of exertional heat injuries, including exertional rhabdomyolysis. This report includes the data for 2016–2020. Additional information about the definition, causes, and prevention of exertional rhabdomyolysis can be found in previous issues of the MSMR.13

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2016 through 31 Dec. 2020. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. All data used to determine incident exertional rhabdomyolysis diagnoses were derived from records routinely maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). These records document both ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System [MHS]) treatment facilities worldwide. In-theater diagnoses of exertional rhabdomyolysis were identified from medical records of service members deployed to Southwest Asia/Middle East and whose health care encounters were documented in the Theater Medical Data Store.

For this analysis, a case of exertional rhabdomyolysis was defined as an individual with 1) a hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter with a diagnosis in any position of either “rhabdomyolysis” (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9]: 728.88; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10]: M62.82) or “myoglobinuria” (ICD-9: 791.3; ICD-10: R82.1) plus a diagnosis in any position of 1 of the following: “volume depletion (dehydration)” (ICD-9: 276.5*; ICD-10: E86.0, E86.1, E86.9), “effects of heat and light” (ICD-9: 992.0– 992.9; ICD-10: T67.0*–T67.9*), “effects of thirst (deprivation of water)” (ICD-9: 994.3; ICD-10: T73.1*), “exhaustion due to exposure” (ICD-9: 994.4; ICD-10: T73.2*), or “exhaustion due to excessive exertion (overexertion)” (ICD-9: 994.5; ICD-10: T73.3*).13 Each individual could be considered an incident case of exertional rhabdomyolysis only once per calendar year.

To exclude cases of rhabdomyolysis that were secondary to traumatic injuries, intoxications, or adverse drug reactions, medical encounters with diagnoses in any position of “injury, poisoning, toxic effects” (ICD-9: 800.*–999.*; ICD-10: S00.*–T88.*, except the codes specific for “sprains and strains of joints and adjacent muscles” and “effects of heat, thirst, and exhaustion”) were not considered indicative of exertional rhabdomyolysis.14

For surveillance purposes, a “recruit trainee” was defined as an active component member in an enlisted grade (E1–E4) who was assigned to 1 of the services’ recruit training locations (per the individual’s initial military personnel record). For this report, each service member was considered a recruit trainee for the period of time corresponding to the usual length of recruit training in his or her service. Recruit trainees were considered a separate category of enlisted service members in summaries of rhabdomyolysis cases by military grade overall.

In-theater diagnoses of exertional rhabdomyolysis were analyzed separately; however, the same case-defining criteria and incidence rules were applied to identify incident cases. Records of medical evacuations from the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) (e.g., Iraq and Afghanistan) to a medical treatment facility outside the CENTCOM AOR also were analyzed separately. Evacuations were considered case defining if affected service members met the above criteria in a permanent military medical facility in the U.S. or Europe from 5 days before to 10 days after their evacuation dates.

It is important to note that medical data from sites that were using the new electronic health record for the Military Health System, MHS GENESIS, between July 2017 and Oct. 2019 are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities from July 2017 through Oct. 2019 were not included in the current analysis.

Results

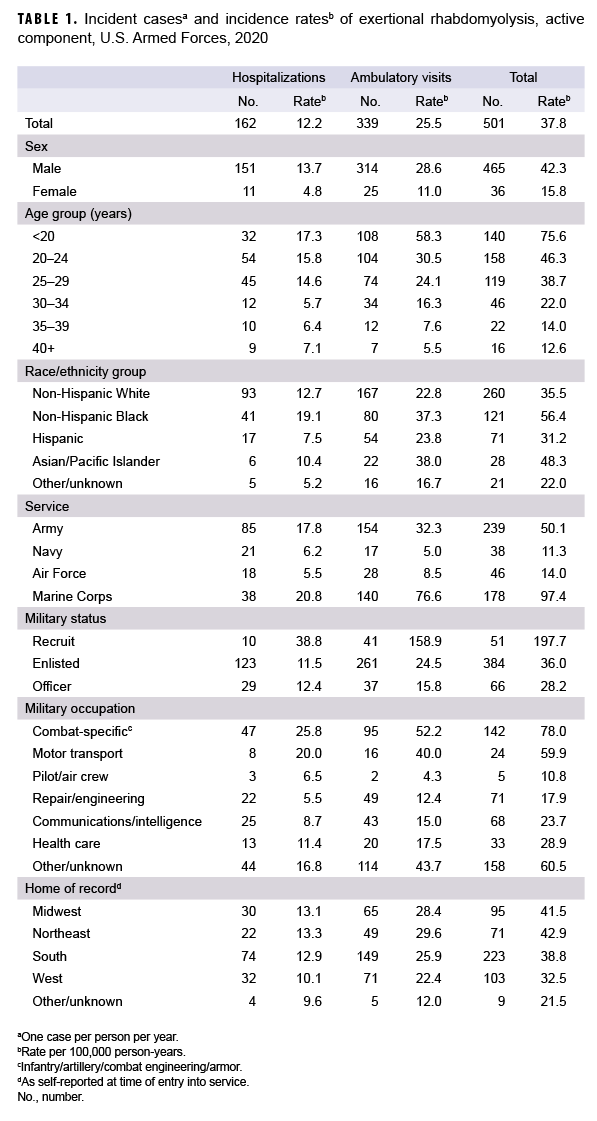

In 2020, there were 501 incident cases of rhabdomyolysis likely associated with physical exertion and/or heat stress (exertional rhabdomyolysis) (Table 1). The crude (unadjusted) incidence rate was 37.8 cases per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs). Subgroup specific incidence rates of exertional rhabdomyolysis were highest among males (42.3 per 100,000 p-yrs), those less than 20 years old (75.6 per 100,000 p-yrs), non-Hispanic Black service members (56.4 per 100,000 p-yrs), Marine Corps or Army members (97.4 per 100,000 p-yrs and 50.1 per 100,000 p-yrs, respectively), and those in combat specific occupations (78.0 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 1). Of note, the incidence rate among recruit trainees was more than 5 times the rates among other enlisted members and officers, even though cases among this group accounted for only 10.2% of all cases in 2020.

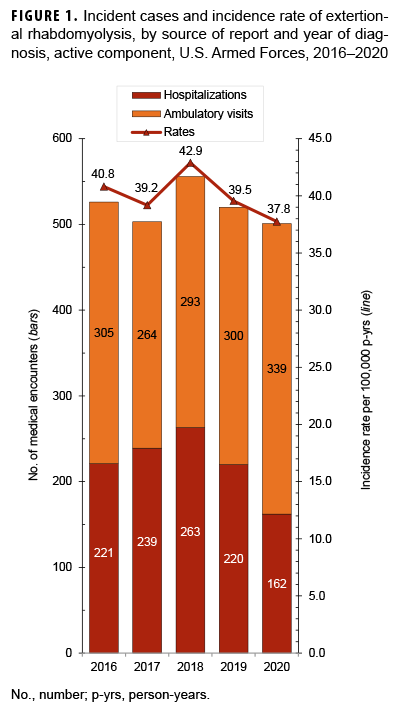

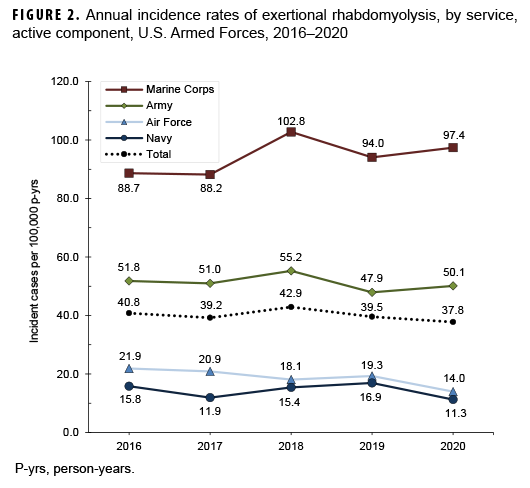

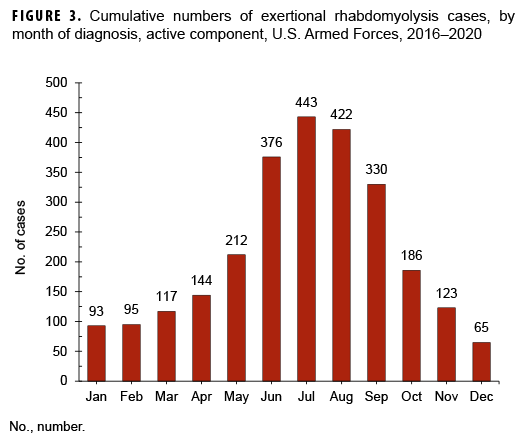

During the surveillance period, crude rates of exertional rhabdomyolysis reached a peak of 42.9 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2018 after which the rate decreased to a low of 37.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020 (Figure 1). The annual incidence rates of exertional rhabdomyolysis were highest among non-Hispanic Blacks in every year except 2018, when the highest rate occurred among Asian/Pacific Islanders (data not shown). Overall and annual rates of incident exertional rhabdomyolysis were highest among service members in the Marine Corps, intermediate among those in the Army, and lowest among those in the Air Force and Navy (Table 1, Figure 2). Among Marine Corps and Army members, annual rates increased between 2016 and 2018 (15.9% and 6.7% increases, respectively), dropped in 2019, and then increased slightly in 2020 (Figure 2). In contrast, annual rates among Air Force and Navy members were relatively stable between 2016 and 2019 and then decreased to their lowest points in 2020. During 2016–2020, three-quarters (75.6%) of the cases occurred during the 6 months of May through Oct. (Figure 3).

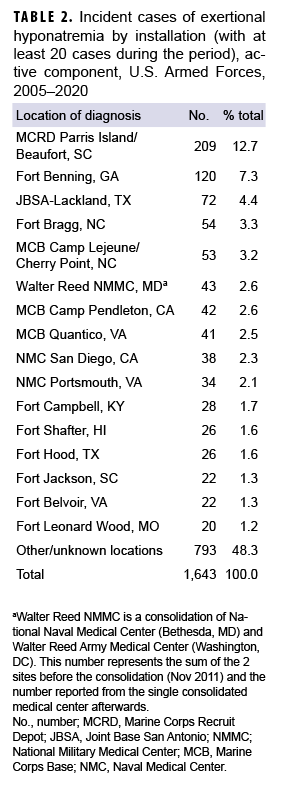

Rhabdomyolysis by location

During the 5-year surveillance period, the medical treatment facilities at 13 installations diagnosed at least 50 cases each; when combined, these installations diagnosed more than half (57.5%) of all cases (Table 2). Of these 13 installations, 4 provide support to recruit/basic combat training centers (Marine Corps Recruit Depot [MCRD] Parris Island/Beaufort, SC; Fort Benning, GA; Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, TX; and Fort Leonard Wood, MO). In addition, 6 installations support large combat troop populations (Fort Bragg, NC; Marine Corps Base [MCB] Camp Lejeune/Cherry Point, NC; MCB Camp Pendleton, CA; Fort Hood, TX; Fort Shafter, HI; and Fort Campbell, KY). During 2016–2020, the most cases overall were diagnosed at MCRD Parris Island/Beaufort, SC (n=283), and Fort Bragg, NC (n=256), which together accounted for about one-fifth (20.7%) of all cases (Table 2).

Rhabdomyolysis in Iraq and Afghanistan

There were 7 incident cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis diagnosed and treated in Iraq/Afghanistan (data not shown) during the 5-year surveillance period. Characteristics of affected servicemembers in Iraq/Afghanistan were generally similar to those who were affected overall. One active component service member was medically evacuated from Iraq/Afghanistan for exertional rhabdomyolysis during the surveillance period; this medical evacuation occurred in Nov. 2020 (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

This report documents that the crude rates of exertional rhabdomyolysis reached a peak of 42.9 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2018 after which the rates decreased to a low of 37.8 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020 (12.0% decrease). Exertional rhabdomyolysis occurred most frequently from early spring through early fall at installations that support basic combat/ recruit training or major Army or Marine Corps combat units.

The risks of heat injuries, including exertional rhabdomyolysis, are elevated among individuals who suddenly increase overall levels of physical activity, recruits who are not physically fit when they begin training, and recruits from relatively cool and dry climates who may not be acclimated to the high heat and humidity at training camps in the summer.1,2,10 Soldiers and Marines in combat units often conduct rigorous unit physical training, personal fitness training, and field training exercises regardless of weather conditions. Thus, it is not surprising that recruit camps and installations with large ground combat units account for most of the cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis.

The annual incidence rates among non-Hispanic Black service members were higher than the rates among members of other race/ethnicity groups in 3 of the 4 previous years, with the exception of 2018. This observation has been attributed, at least in part, to an increased risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis among individuals with sickle cell trait (SCT)15–18 and is supported by studies among U.S. service members.10,19,20 The rhabdomyolysis-related deaths of 2 SCT-positive service members (an Air Force member and a Navy recruit) after physical training in 2019 highlight this elevated risk.21,22 However, although it is well established that sickle cell trait is positively associated with exertional rhabdomyolysis, its association with disease progression and severity is unclear and warrants further study.19,20 Currently, the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps conduct laboratory screening for SCT for all accessions. In addition, some service-specific SCT-related precautions are in place prior to mandatory physical fitness testing (e.g., questions about SCT status on fitness questionnaires; wearing colored belts, arm bands, or tags).

The findings of this report should be interpreted with consideration of its limitations. A diagnosis of "rhabdomyolysis" alone does not indicate the cause. Ascertainment of the probable causes of cases of exertional rhabdomyolysis was attempted by using a combination of ICD-9/ICD-10 diagnostic codes related to rhabdomyolysis with additional codes indicative of the effects of exertion, heat, or dehydration. Furthermore, other ICD-9/ICD-10 codes were used to exclude cases of rhabdomyolysis that may have been secondary to trauma, intoxication, or adverse drug reactions.

The measures that are effective at preventing exertional heat injuries in general apply to the prevention of exertional rhabdomyolysis. In the military training setting, the risk of exertional rhabdomyolysis can be reduced by emphasizing graded, individual preconditioning before starting a more strenuous exercise program and by adhering to recommended work/rest and hydration schedules, especially in hot weather. The physical activities of management after treatment for exertional rhabdomyolysis, including the decision to return to physical activity and duty, is a persistent challenge among athletes and military members.10,,11,23 It is recommended that those who have had a clinically confirmed exertional rhabdomyolysis event be further evaluated and risk stratified for recurrence before return to activity/ duty.7,11,23,24 Low-risk patients may gradually return to normal activity levels, while those deemed high risk for recurrence will require further evaluative testing (e.g., genetic testing for myopathic disorders).23,24

Commanders and supervisors at all levels should ensure that guidelines to prevent heat injuries are consistently implemented, be vigilant for early signs of exertional heat injuries, and intervene aggressively when dangerous conditions, activities, or suspicious illnesses are detected. Finally, medical care providers should consider exertional rhabdomyolysis in the differential diagnosis when service members (particularly recruits) present with muscular pain or swelling, limited range of motion, or the excretion of darkened urine (possibly due to myoglobinuria) after strenuous physical activity, especially in hot, humid weather.

References

- Zutt R, van der Kooi AJ, Linthorst GE, Wanders RJ, de Visser M. Rhabdomyolysis: review of the literature. Neuromuscul Disord. 2014;24(8):651–659.

- Beyond muscle destruction: a systematic review of rhabdomyolysis for clinical practice. Chavez L, Leon M, Einav S, Varon J. Crit Care. 2016;20:135.

- Rawson ES, Clarkson PM, Tarnopolsky MA. Perspectives on exertional rhabdomyolysis. Sports Med. 2017;47(suppl 1):33–49.

- McKewon S. Two Nebraska football players hospitalized, treated after offseason workout. Omaha World-Herald. 20 January 2019. Accessed 29 March 2021. https://www.omaha.com/huskers/football/two-nebraska-football-players-hospitalizedtreated-after-offseason-workout/article_d5929674-53a7-5d90-803e-6b4e9205ee60.html

- Raleigh MF, Barrett JP, Jones BD, Beutler AI, Deuster PA, O'Connor FG. A cluster of exertional rhabdomyolysis cases in a ROTC program engaged in an extreme exercise program. Mil Med. 2018;183(suppl 1):516–521.

- Bosch X, Poch E, Grau JM. Rhabdomyolysis and acute kidney injury. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(1):62–72.

- O’Connor FG, Deuster P, Leggit J, et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Exertional Rhabdomyolysis in Warfighters 2020. Bethesda, Maryland: Uniformed Services University. 2020.

- Hill OT, Wahi MM, Carter R, Kay AB, McKinnon CJ, Wallace RF. Rhabdomyolysis in the U.S. active duty Army, 2004–2006. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2012;44(3):442–449.

- Lee G. Exercise-induced rhabdomyolysis. R I Med J. 2014;97(11):22–24.

- Hill OT, Scofield DE, Usedom J, et al. Risk factors for rhabdomyolysis in the U.S. Army. Mil Med. 2017;182(7):e1836–e1841.

- Knapik JJ, O’Connor FG. Exertional rhabdomyolysis: epidemiology, diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. J Spec Oper Med. 2016;15(3):65–71.

- Holt S, Moore K. Pathogenesis of renal failure in rhabdomyolysis: the role of myoglobin. Exp Nephrol. 2000;8(2):72–76.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Exertional rhabdomyolysis among active component members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2014–2018. MSMR. 2019;26(4):21–26.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance case definition. Exertional rhabdomyolysis. Accessed 29 March 2021. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2017/03/01/Rhabdomyolysis-Exertional

- Gardner JW, Kark JA. Fatal rhabdomyolysis presenting as mild heat illness in military training. Mil Med. 1994;159(2):160–163.

- Makaryus JN, Catanzaro JN, Katona KC. Exertional rhabdomyolysis and renal failure in patients with sickle cell trait: is it time to change our approach? Hematology. 2007;12(4):349–352.

- Ferster K, Eichner ER. Exertional sickling deaths in Army recruits with sickle cell trait. Mil Med. 2012;177(1):56–59.

- Naik RP, Smith-Whitley K, Hassell KL, et al. Clinical outcomes associated with sickle cell trait: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(9):619–627.

- Nelson DA, Deuster PA, Carter R, Hill OT, Wolcott VL, Kurina LM. Sickle cell trait, rhabdomyolysis, and mortality among U.S. Army soldiers. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(5):435–442.

- Webber BJ, Nye NS, Covey CJ, et al. Exertional Rhabdomyolysis and Sickle Cell Trait Status in the U.S. Air Force, January 2009–December 2018. MSMR. 2021;28(1):15–19.

- Air Combat Command. U.S. Air Force Ground Accident Investigation Board Report. 20th Component Maintenance Squadron 20th Fighter Wing, Shaw Air Force Base, South Carolina. Fitness assessment fatality; 24 May 2019.

- Mabeus C. Autopsy reports reveal why two recruits died at boot camp. NavyTimes. 8 November 2019. Accessed 7 April 2021.https://www.navytimes.com/news/your-navy/2019/11/08/autopsyreports-reveal-why-two-recruits-died-at-boot-camp/

- O’Connor FG, Brennan FH Jr, Campbell W, Heled Y, Deuster P. Return to physical activity after exertional rhabdomyolysis. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7(6):328–331.

- Atias D, Druyan A, Heled Y. Recurrent exertional rhabdomyolysis: coincidence, syndrome, or acquired myopathy? Curr Sports Med Rep. 2013;12(6):365–369.