Abstract

Glaucoma is an eye disease that involves progressive optic nerve damage and vision loss, leading to blindness if undetected or untreated. This report describes an analysis using the Defense Medical Surveillance System to identify all active component service members with an incident diagnosis of glaucoma during the period between 2013 and 2017. The analysis identified 37,718 incident cases of glaucoma and an overall incidence rate of 5.9 cases per 1,000 person-years (p-yrs). The majority of cases (97.6%) were diagnosed at an early stage as borderline glaucoma; of these borderline cases, 2.2% progressed to open-angle glaucoma during the study period. No incident cases of absolute glaucoma, or total blindness, were identified. Rates of glaucoma were higher among non-Hispanic black (11.0 per 1,000 p-yrs), Asian/Pacific Islander (9.5), and Hispanic (6.9) service members, compared with non-Hispanic white (4.0) service members. Rates among female service members (6.6 per 1,000 p-yrs) were higher than those among male service members (5.8). Between 2013 and 2017, incidence rates of glaucoma diagnoses increased by 75.4% among all service members.

What Are the New Findings?

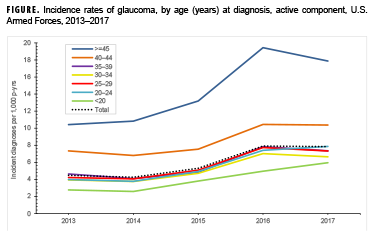

The vast majority of glaucoma diagnoses in active component service members (97.6%) represent early stage disease (borderline or suspect glaucoma). Over the surveillance period, incidence rates of glaucoma diagnoses increased by 75.4% overall; the greatest increase occurred in service members <20 years of age, which may reflect improved detection among younger service members.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

There is no cure for glaucoma, and vision loss caused by glaucoma does not return with treatment; treatment only stops or reduces the rate of new vision loss. Glaucoma prevention efforts should continue to focus on early detection through periodic and comprehensive eye examinations performed by an eye care professional (optometrist or ophthalmologist).

Background

Glaucoma refers to a group of eye diseases that can damage the optic nerve and can result in vision loss and blindness. This condition is often, but not always, associated with elevated intraocular pressure (IOP), also called ocular hypertension. Elevated IOP can be the result of excessive production of aqueous humor, reduced flow of fluid out of the eye, or both. Aqueous humor is a transparent fluid that fills the anterior and posterior chambers of the eye and that flows passively out of the eye. Elevated pressure not relieved by treatment is believed to result in optic nerve damage in most affected individuals.1 Usually, damage to the optic nerve and loss of visual field are gradual and painless; however, there is a form of the disease called acute angle closure in which the trabecular meshwork becomes blocked, leading to a rapid rise in IOP and eye pain. This urgent condition requires immediate treatment.2

A finding of elevated IOP alone is insufficient to diagnose glaucoma, but it is 1 of the findings that can be used to classify a patient with glaucoma suspect or borderline glaucoma. The American Academy of Ophthalmology defines glaucoma suspect as having 1 of the following findings in at least 1 eye: consistently elevated IOP, optic nerve deterioration or nerve fiber layer defect suggestive of glaucoma, or a visual field abnormality consistent with glaucoma. A diagnosis of primary open angle glaucoma (POAG) is supported when 2 or more of these findings are present, especially in the presence of other established risk factors.3,4 POAG is the most common form of glaucoma. In this form, the drainage area between the cornea and the iris, which forms an angle, is open but aqueous fluid flow is inadequate. In angle-closure glaucoma, the angle is reduced or blocked by the iris. Other less common forms of the disease include steroid-induced glaucoma and disease associated with developmental anomalies and systemic syndromes. There are also congenital forms of the disease that are diagnosed at birth or in early childhood.1 The end stage of the disease, termed absolute glaucoma, is total blindness.

Risk factors for the development of glaucoma include elevated IOP, being 60 years of age or older, being of black, Asian, or Hispanic race/ethnicity, and having a family history of glaucoma.5,6 Comorbid conditions associated with increased risk for glaucoma include hypertension, diabetes, uveitis, eye injuries, and eye conditions requiring extended corticosteroid use.6

Among U.S. adults, glaucoma ranks among the top 3 most common causes of blindness.7 Estimates of glaucoma prevalence in the U.S. vary widely based on study population and whether estimates include those considered borderline or glaucoma suspect. Using data from the 2005–2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), Gupta et al. estimated that the overall prevalence of glaucoma in U.S. civilians 40 years of age or older is 2.1%, which represents approximately 2.9 million cases.8

Glaucoma is considered a disqualifying condition for enlistment in the military.9 Glaucoma that is diagnosed while in service but deemed resistant to treatment or that affects the visual field will be evaluated by a medical evaluation board for possible separation from service.9 A prior MSMR analysis identified more than 117,000 incident cases of glaucoma in active component service members between 1998–2013 but noted that incidence rates had declined for those service members 44 years of age or older during the surveillance period.10 In addition, 94.5% of cases were borderline or glaucoma suspect cases.10 The current analysis updates the prior MSMR report using data from 2013–2017.

Methods

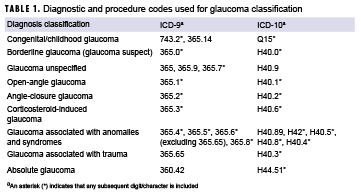

The Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) was used to identify all active component service personnel (Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines) whose health care records contained a diagnosis of glaucoma during 1 Jan. 2013 through 31 Dec. 2017. The DMSS contains administrative records for all medical encounters of military service members who are hospitalized or receive ambulatory care at military treatment facilities or through civilian Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care if paid for by the Military Health System. A case of glaucoma was defined as having 1) at least 1 inpatient encounter with a diagnosis of glaucoma in any diagnostic position, 2) at least 1 outpatient encounter from an optometry or ophthalmology clinic (Medical Expense and Reporting System code beginning with "BBD" or "BHC") with a diagnosis of glaucoma in any diagnostic position, or 3) at least 2 outpatient or in-theater (Theater Medical Data Store) medical encounters within 180 days with a diagnosis of glaucoma in any diagnostic position.;

The incidence date was defined as the earliest medical encounter that qualified the service member as a case. An individual was counted as an incident case only once during the study period, and person-time for service members with glaucoma was censored at the time of the incident diagnosis. Service members with incident diagnoses prior to 2013 or with an incident diagnosis while in the reserve or guard components were excluded. Denominators for incidence rates of glaucoma were calculated based on the total active component person-time in years for each year in the study period. The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used to define glaucoma, including classification of glaucoma type, are provided in Table 1.

Disease progression was analyzed by evaluating changes in glaucoma type over time for each service member. A glaucoma case was estimated to have progressed if the incident diagnosis was for borderline, congenital, or unspecified glaucoma and was followed by a medical encounter with a diagnosis that was more specific or severe than the initial diagnosis (e.g., open-angle, angle-closure, or absolute).

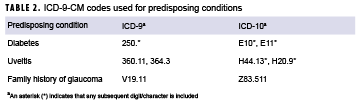

In addition to estimating the incidence of glaucoma, the overall burden of glaucoma was measured by counting the number of medical encounters with a primary diagnosis of glaucoma. Risk factors for glaucoma were also identified. These conditions were defined by having at least 1 diagnosis in any diagnostic position of diabetes, family history of glaucoma, or uveitis (Table 2) occurring on or prior to the incident diagnosis of glaucoma.

The average time from incident diagnosis to separation from military service was measured overall and by incident glaucoma type. This analysis was performed on a sub-group of service members who left service between 2013 and 2017 and included incident cases of glaucoma that were diagnosed prior to 2013.

Results

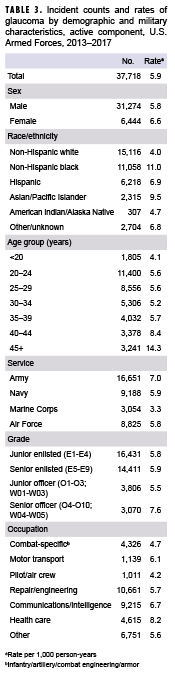

During the 5-year surveillance period, a total of 37,718 incident cases of glaucoma were identified. This represents an overall incidence rate of 5.9 per 1,000 person-years (p-yrs) (Table 3). The rate of incident glaucoma diagnoses among female service members (6.6 per 1,000 p-yrs) was 14% higher than that of male service members (5.8 per 1,000 p-yrs). The rate was highest among non-Hispanic black service members (11.0 per 1,000 p-yrs) and it was more than double the rate among non-Hispanic white service members (4.0 per 1,000 p-yrs). Rates among both Asian/Pacific Islander (9.5 per 1,000 p-yrs) and Hispanic (6.9 per 1,000 p-yrs) service members were also elevated in comparison with non-Hispanic white service members.

The incidence rate of glaucoma diagnosis increased with increasing age (Table 3). Between 2013 and 2017, incidence rates of glaucoma diagnoses increased by 75.4% among all service members (Figure). When viewed over time, rates among service members increased over the surveillance period in all age groups (Figure). The rate in 2017 among service members aged 45 years or older was 17.9 per 1,000 p-yrs. This represents an increase of 71.5% from 2013. The 2017 rate demonstrated an 8% decline from the 2016 rate, which, at 19.4 cases per 1,000 p-yrs, was the highest rate during the surveillance period. Glaucoma diagnosis rates among service members younger than 20 years of age increased 115% over the study period. (Figure)

Overall, the incidence rate of glaucoma diagnosis was highest among Army personnel (7.0 per 1,000 p-yrs) and lowest among Marines (3.3 per 1,000 p-yrs) (Table 3). Junior officers (5.5 per 1,000 p-yrs) had the lowest rates by grade, followed by junior enlisted (5.8 per 1,000 p-yrs) and senior enlisted (5.9 per 1,000 p-yrs) personnel. Senior officers had the highest rates of glaucoma diagnoses compared to their junior and enlisted counterparts. When stratified by occupational category, service members whose primary occupational code categorized them in health care or communications/intelligence occupations had higher rates of glaucoma diagnoses than those working in other occupations.

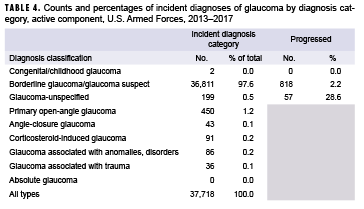

Diagnosis categories and disease progression

When the incident diagnoses were grouped by disease type, 97.6% of the cases were classified as borderline glaucoma or glaucoma suspect (Table 4). The next largest category was POAG, which represented 1.2% of the cases. Less than 1 percent of the incident cases were coded as any other type of glaucoma. Of those service members with an initial diagnosis of borderline glaucoma, 2.2% later received a diagnosis of POAG or other more severe glaucoma diagnoses.

Burden

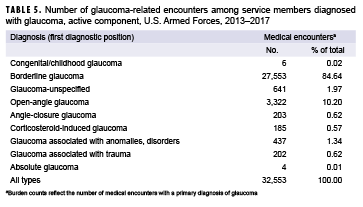

Among 37,718 diagnosed cases, there were 32,553 such medical encounters. An individual could become a diagnosed case without receiving a glaucoma diagnosis in the primary diagnostic position; however, to be counted in the burden analysis, a glaucoma diagnosis was required to be in the primary diagnostic position which accounts for the difference in the number of diagnosed cases versus the number of medical encounters ascertained in the burden analysis. Table 5 shows the number and percentage of medical encounters when categorized by the glaucoma diagnosis made in the primary diagnostic position. Even though borderline glaucoma represented 97.6% of the incident cases, this diagnosis represented only 84.6% of total medical encounters with a glaucoma diagnosis in the first diagnostic position. The 1.2% of service members with an incident diagnosis of POAG or who progressed to POAG utilized 10.2% of total medical encounters.

Comorbidities

Overall, 1.6% of those with a glaucoma diagnosis had also been diagnosed with diabetes, while less than 1% (0.3%) of glaucoma cases had a family history of glaucoma documented via diagnosis prior to their glaucoma diagnosis. Pre-existing uveitis was more common among those with glaucoma associated with anomalies and other disorders (22.1%) and in those with unspecified glaucoma (4.0%), while overall, 1.1% of all incident glaucoma cases had a pre-existing uveitis diagnosis (data not shown).

Career impact

The median time to separation or death among service members diagnosed with glaucoma did not vary much when analyzed by the incident diagnosis. On average, the shortest amount of time served following the initial diagnosis with any type of glaucoma occurred among those initially diagnosed with corticosteroid-induced glaucoma (3.3 years), followed by those diagnosed with glaucoma associated with trauma (3.8 years) (data not shown). The longest amount of time served following initial diagnosis occurred among those initially diagnosed with POAG (8.3 years). On average, service members served for 4.5 years following any initial glaucoma diagnosis (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

The results of this analysis indicate that most service members (97.6%) initially diagnosed with glaucoma are in the early stages of the disease (borderline or suspect glaucoma). This finding is similar to the previous MSMR analysis in which 94.5% of incident glaucoma diagnoses fell into this category.10 These diagnoses of borderline glaucoma/glaucoma suspect may reflect cases with transient elevation in IOP, which may never result in nerve damage. Most types of glaucoma progress slowly and can be managed well with medication to reduce aqueous fluid production or increase fluid outflow. Eventually, some cases may require surgery to enable better fluid drainage.1,2 Among service members whose disease progressed beyond the borderline diagnosis, prior to separation from service or the end of the study period, the most common form of glaucoma was POAG.

The incidence rates of glaucoma diagnoses increased with age and among all age groups over the study period. The greatest increase over time in rates occurred among the youngest age groups. These findings may reflect improved detection of borderline glaucoma among younger service members. The striking increase in incidence rates in younger service members likely reflects increased ascertainment, possibly due to more frequent measurement of intraocular pressure in this population. Incidence rates by service were lowest among Marines, which likely reflects the younger age distribution of this service. Rates by occupational category at incident diagnosis were highest among health care workers, possibly due to increased health care-seeking behaviors in this group.

As seen in civilian populations, incidence of glaucoma was higher among non-Hispanic black, Asian/Pacific Islander, and Hispanic service members compared with non-Hispanic white or American Indian/Alaska Native service members.

Not surprisingly, the majority of medical encounters for glaucoma (85%) had a primary diagnosis indicating borderline or glaucoma suspect. Because the majority of incident cases in this analysis were classified as borderline glaucoma or glaucoma suspect, this finding is not unexpected. Notably, this finding differs from the previous MSMR analysis of glaucoma burden because of differences in the methodology used to assess the burden of disease. The 2014 MSMR analysis included any medical encounters with any diagnosis of glaucoma in any diagnostic position in assessing the burden of disease for glaucoma cases.10 In addition, the prior burden analysis attributed glaucoma medical encounters to the most severe glaucoma diagnosis a case had received. In other words, if the most severe diagnosis a case had received was for POAG, burden medical encounters would be attributed to POAG, even when the medical encounter itself may have had a less severe diagnosis (e.g. borderline or glaucoma suspect) listed in the primary diagnostic position. In contrast, the current burden analysis classified medical encounters by the glaucoma diagnosis listed in the primary diagnostic position of the medical encounter, which is consistent with the standard MSMR burden methodology used in its annual burden analysis.11 The net result of this difference in methodology is that fewer medical encounters overall were included in the burden analysis and a greater proportion of encounters were classified as borderline or glaucoma suspect. These findings should be interpreted in light of this methodological difference.

Most types of glaucoma cause no symptoms until damage to the optic nerve and visual field loss is substantial. For this reason, the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health recommends that individuals with risk factors for glaucoma should receive regular comprehensive dilated eye exams. Those with increased risk include anyone with a family history of glaucoma, those with diabetes, African Americans older than 40 years of age, and individuals 60 years of age or older.12

One limitation of this analysis is that an unknown number of the incident diagnoses of borderline glaucoma may reflect a transient elevation of IOP, which, while properly identified during the medical encounter, may never progress to glaucoma, which requires damage to the optic nerve. Therefore, the incidence rates of glaucoma reported here are likely overestimates of the population truly at risk for advanced disease. It is also possible that many service members diagnosed with borderline glaucoma did not receive a subsequent diagnosis with a more advanced form of the disease during the period covered by this analysis because of the slow nature of the progression of the disease and the fact that many separate from service before the disease becomes problematic.

References

- Cioffi G. Section 10: Glaucoma. 2011–2012 Basic and Clinical Science Course: American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2012:1–12.

- National Eye Institute. Facts About Glaucoma. https://www.nei.nih.gov/health/glaucoma/glaucoma_facts. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2014.

- American Academy of Opthamology. Preferred practice pattern: Primary open-angle glaucoma. Nov. 2015. http://one.aao.org/. Accessed on 02 Jan. 2019.

- American Academy of Opthamology. Preferred practice pattern: Primary open-angle glaucoma suspect. Nov. 2015. http://one.aao.org/. Accessed on 02 Jan. 2019.

- Mayo Clinic. Diseases and Conditions, Glaucoma. http://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/glaucoma/basics/risk-factors/con-20024042. Accessed on 18 Nov. 2014.

- Zhang X, Cotch MF, Ryskulova A, et al. Vision health disparities in the United States by race/ethnicity, education, and economic status: Findings from two nationally representative surveys. Am J Ophthalmol. 2012;154(6 Suppl):S53–S62 e51.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vision Health Initiative (VHI). https://www.cdc.gov/visionhealth/basics/ced/index.html. Accessed on 10 Jan. 2019.

- Gupta P, Zhao D, Guallar E, Ko F, Boland MV, Friedman DS. Prevalence of glaucoma in the United States: The 2005-2008 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016;57(6):2905–2913.

- Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03. Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services. 2011.

- Hurt L. Glaucoma, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 1998-2013. MSMR. 2014;21(12):17-23.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, deployed active and reserve component service members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2017. MSMR. 2018;25(5):26–31.

- National Eye Institute. National Eye Institute Statement on Detection of Glaucoma and Adult Vision Screening. https://www.nei.nih.gov/nehep/programs/glaucoma/detection. Accessed on 24 Dec. 2018.