Abstract

This analysis summarizes the prevalence of testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) during 2017 among active component service men by demographic and military characteristics. This analysis also determines the percentage of those receiving TRT in 2017 who had an indication for receiving TRT using the 2018 American Urological Association (AUA) clinical practice guidelines. In 2017, 5,093 of 1,076,633 active component service men filled a prescription for TRT, for a period prevalence of 4.7 per 1,000 male service members. After adjustment for covariates, the prevalence of TRT use remained highest among Army members, senior enlisted members, warrant officers, non-Hispanic whites, American Indians/Alaska Natives, those in combat arms occupations, health care workers, those who were married, and those with other/unknown marital status. Among active component male service members who received TRT in 2017, only 44.5% met the 2018 AUA clinical practice guidelines for receiving TRT.

What Are the New Findings?

In 2017, the prevalence of TRT use among active component service men was 4.7 per 1,000. Using the 2018 AUA clinical practice guidelines, only 44.5% of those receiving TRT had an indication to be on the medication.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Out of every 1,000 male service members, almost 3 are inappropriately receiving TRT. Those being inappropriately treated may experience adverse effects of the medication, including obstructive sleep apnea, worsening of urinary tract symptoms, and edema. These adverse effects have the potential to impact deployability and medical readiness.

Background

Testosterone deficiency, also known as hypogonadism or testicular hypofunction, is a combined biochemical and clinical syndrome in adult males characterized by low levels of circulating total testosterone that may adversely affect multiple organ systems and quality of life.1 In healthy men aged 18–50 years, total serum testosterone levels range from 300 ng/dl to 1000 ng/dl.2 These levels start to fall significantly after 50 years of age.2 The Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging found that 12% of men in their 50s and 50% of men in their 80s had total serum testosterone levels below 325 ng/dl.3 The average drop in testosterone is estimated at 3 ng/dl per year for men in their 50s and 11 ng/dl per year for men in their 80s.1 When hypogonadism is defined as a total serum testosterone level less than 300 ng/dl combined with symptomatic clinical criteria, the estimated prevalence of testosterone deficiency in the U.S. ranges from 5.6% to 6.5%.4

The American Urological Association (AUA) 2018 guidelines for the evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency recommend that clinicians use a total serum testosterone level below 300 ng/dl as a reasonable cutoff in support of the diagnosis of low testosterone.5 An additional recommendation was that the laboratory diagnosis of low testosterone should be made only after 2 total testosterone level measurements below 300 ng/dl on serum specimens taken on separate occasions.5 Finally, the AUA recommendation for a clinical diagnosis of testosterone deficiency is at least 1 total testosterone level below 300 ng/dl in addition to appropriate physical, cognitive, and/or sexual signs and symptoms.5,6 These clinical signs and symptoms include fatigue, reduced energy, reduced endurance, diminished physical performance, loss of body hair, reduced lean muscle mass, obesity, depressive symptoms, cognitive dysfunction, reduced motivation, poor concentration, poor memory, irritability, reduced sex drive, and reduced erectile function.2,5

Testosterone level testing and testosterone replacement therapy (TRT) prescriptions have tripled in recent years, and the estimated prevalence of TRT use among men in the U.S. is 0.9–2.9%.4,5 However, some men are prescribed TRT without an indication.5 The AUA estimates that up to 25% of men who eventually receive TRT do not have their testosterone levels checked prior to initiation of therapy. Furthermore, it is estimated that approximately 30% of men who are placed on TRT have no indication for the medication.5,7 The U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) also reported a marked increase in the number of veterans who requested TRT for low testosterone levels.8 As of 2015, more than 85,000 veterans had received TRT through the VA.9 Many of these veterans insisted that their symptoms were due to "low T," despite having laboratory results indicating normal serum total testosterone levels.9 In the Military Health System (MHS), there also have been significant increases in the numbers of both TRT and testicular hypofunction diagnoses. From 2007–2011, males aged 25–44 years received androgen prescriptions at rates that increased 30% per year. During this same period, rates of medically coded hypogonadism increased over 40% per year.10

There are significant side effects and risks associated with TRT. TRT has been associated with an increased risk of adverse cardiovascular, respiratory, and dermatologic events among older men.11 There is inconsistent evidence about the effects of TRT in a military age population (17–60 years). Several studies noted adverse effects of TRT in younger populations including topical transference, erythrocytosis, interference with fertility, worsening of severe lower urinary tract symptoms, suppression of spermatogenesis, fluid retention and edema, and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).5,6 One recent study noted an increased risk of OSA but no increased risk of cardiovascular or thromboembolic events.12 With the increasing number of testosterone deficiency diagnoses and potential health risks associated with initiation of TRT, it is important to understand the epidemiology of receipt of TRT by U.S. service men and whether these individuals have an indication for receiving treatment. Previous studies of U.S. service men highlighted the need to connect individual prescriptions with a patient's androgen level in order to evaluate the appropriateness of prescribed TRT.10

Methods

Data were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which contains records of ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces in military and civilian (if reimbursed through the MHS) treatment facilities. The DMSS also contains administrative records for prescriptions dispensed to service members at military treatment facilities (MTFs) or through civilian Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care. In addition, laboratory data were obtained from the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center (NMCPHC), which include data from the Health Level 7 (HL7) database generated within the Composite Health Care System (CHCS) at fixed MTFs. Laboratory testing performed in civilian facilities is not captured in the HL7 database.

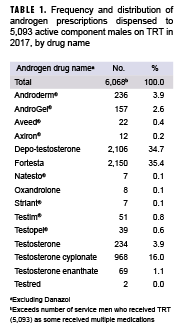

The prevalence of TRT utilization during 2017 was defined as the number of service men who had a dispensed prescription in 2017 with a therapeutic class code for androgens (excluding Danazol), among all male active component service members in the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps in service during June 2017. Frequency and distribution of the dispensed androgen prescriptions were identified for each service man (Table 1). Covariates included service, age, military rank, race/ethnicity, military occupation, and marital status. Adjusted prevalence estimates were calculated using log binomial regression. All analyses were performed using SAS/STAT® software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

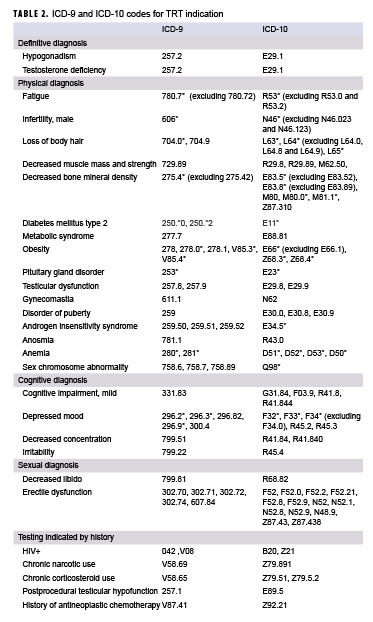

Laboratory tests and medical encounter history were examined for evidence of an indication for TRT among service men with a TRT prescription in 2017. NMCPHC was provided a line listing of service men who received a TRT prescription in 2017. NMCPHC then returned a line listing of those service men with total serum testosterone test results below 300 ng/dl. Total serum testosterone tests conducted prior to the last TRT prescription in 2017 were considered. Laboratory testing data were available for the period from May 2004 through 2017 for Navy service men and July 2006 through 2017 for all other service men. Electronic health records of service men with a TRT prescription in 2017 were also examined for a history of a qualifying diagnosis as indicated by any of the ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes presented in Table 2. These codes were identified after review of the relevant literature and current clinical practice guidelines from the Endocrine Society and the AUA.1,2,5,6 Service men were defined as having a prior indication for TRT if they met the AUA recommendations for 1) laboratory diagnosis (i.e., 2 total testosterone measurements less than 300 ng/dl) and/or 2) clinical diagnosis (i.e., at least 1 total testosterone measurement less than 300 ng/dl and at least 1 qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis code).5

Results

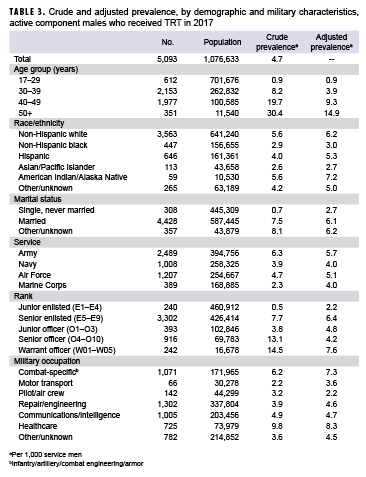

During the 1-year surveillance period, a total of 5,093 active component service men had a filled prescription for TRT, yielding a crude period prevalence of 4.7 per 1,000 male service members (Table 3). Army service men had a higher prevalence of TRT use compared to men in the other service branches (6.3 per 1,000). Warrant officers (14.5 per 1,000) and senior officers (13.1 per 1,000) had a higher prevalence of TRT use compared to enlisted personnel (senior enlisted, 7.7 per 1,000; junior enlisted, 0.5 per 1,000) and junior officers (3.8 per 1,000). In addition, TRT use increased approximately linearly with increasing age as seen in Table 3. Non-Hispanic whites and American Indian/Alaska Native service men had the highest prevalence (5.6 per 1,000) compared to service men in other race/ethnicity groups, while non-Hispanic blacks (2.9 per 1,000) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (2.6 per 1,000) had the lowest. Health care workers had the highest prevalence (9.8 per 1,000) compared to those in other occupations, while motor transport workers had the lowest (2.2 per 1,000). Finally, service members who were never married had a TRT prevalence of 0.7 per 1,000, while married service men and those with “other/unknown” marital status had a prevalence of 7.5 and 8.1 per 1,000, respectively.

After adjusting for all covariates (Table 3), the prevalence of TRT use remained highest among Army members, senior enlisted members, warrant officers, non-Hispanic whites, American Indian/Alaska Natives, those in combat arms occupations, health care workers, those who were married, and those with other/unknown marital status.

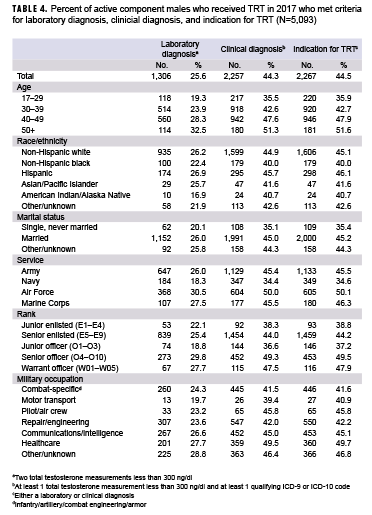

Among the 5,093 active component male service members who received TRT in 2017, 25.6% met the laboratory diagnosis criterion of having at least 2 total testosterone measurements that were less than 300 ng/dl. In addition, 44.3% of the service men who received TRT met the clinical diagnosis criteria of having at least 1 total testosterone measurement less than 300 ng/dl and documentation of at least 1 qualifying diagnosis code. Nearly all (99%) of the service men who met the laboratory diagnosis criterion also met the clinical diagnosis criteria. Overall, 44.5% of those who received TRT met the case definition for an indication for TRT (Table 4). Nearly 2 out of every 3 service men in the Navy (65.4%) and service men aged 17–29 years (64.1%) who received TRT did so without an indication for TRT.

Editorial Comment

The crude prevalence of TRT of 4.7 per 1,000 service men, or 0.5%, is well below the general U.S population estimate of 0.9–2.9%.1 This is expected since the U.S. Department of Defense (DOD) active component population is younger on average than the general population, is screened for pre-existing conditions prior to accession into the military, and includes few individuals over 60 years of age. In addition, there is a pronounced gradient of increasing prevalence of TRT use with increasing age. This pattern is consistent with the published literature on the civilian population and the known biological process of aging.2

Before and after adjustment, there were pronounced differences in the prevalence of TRT use between some occupations. The increased prevalence of TRT use among health care workers may be related to medical knowledge, access to care, and/or availability of treatment. The higher prevalence observed among those in combat arms occupations could be related to the nature of their work and the associated clinical symptoms. These warfighters are chronically sleep deprived, and that can manifest as depression, fatigue, and irritability.13 In contrast, pilots and aircrew are anecdotally known for their refusal to seek care, even to the point of concealing illness and injuries, in order to maintain their flight status. Hypogonadism diagnoses result in pilots and aircrew losing their flight status14; they then must go through the medical waiver process to regain their certifications.14 This is a potential explanation for why the prevalence of TRT use in pilots and aircrew is much lower than among service men in other occupational groups. Even after adjustment, there remains an association between TRT and marital status. Compared to single service men, married service men may be more likely to seek care related to difficulties with conceiving a child or because of spousal encouragement to seek care for other comorbid conditions associated with hypogonadism.

Overall, 44.5% of those active component men who received TRT had an indication for receiving treatment when following the 2018 AUA clinical practice guidelines for the management of testosterone deficiency. The finding of 44.5% is substantially less than the AUA’s estimation for 70% in the civilian population; however, this could be related to differences in the age distributions of the study populations. The AUA estimation was derived from a 2015 study that used the North Shore University Health System Data Warehouse. However, the average age of the study population was 56 years.7 In contrast, in the current study, over 90% of the service men on TRT in 2017 were under the age of 50. Older men are more likely to have an indication for TRT because of a higher prevalence of hypogonadism.

This study was limited to active component service men, so comparisons with studies of the civilian population should be regarded with caution given the differences between the 2 populations in terms of age and health status. Furthermore, the data captured in this report may not represent service men’s true medical histories, as some members may have been evaluated by non-network civilian providers and possibly paid the costs for this medical care out-of-pocket or through private health insurance. Diagnostic records, laboratory data, and prescription data associated with such non-network health care would not have been included in the current analysis. In addition, subjective signs and symptoms derived from questionnaires have been shown to have poor sensitivity whereas the clinical diagnosis criteria used in the current analysis were based upon a consolidation of definitions of hypogonadism reported in the published literature.1,2,5,6 Finally, in some general population studies, treatment for hypogonadism was based upon other criteria. The 2018 AUA guidelines were released after the surveillance period. Prior to the release of these guidelines, there were no commonly accepted standards for diagnosing hypogonadism.

During 2017, approximately 1 out of every 200 service men (0.47%) was treated with TRT. While this is a smaller percentage than that observed in the civilian population, it still represents a fairly large number of service men. Primary care providers in the MHS should be aware of the prevalence of TRT use in order to properly assess patients presenting with comorbid conditions. Furthermore, those providers who are considering initiating TRT should be aware of the 2018 AUA guidelines in order to reduce the frequency of TRT prescriptions that lack valid indications. The DOD might consider limiting initiation of TRT to those providers with appropriate board certification or other specialized training in order to limit the frequency of inappropriate TRT prescriptions. Such a limitation could lessen the frequency of inappropriate prescriptions of long-term medications by physicians who have not yet completed residency training. Finally, future studies are recommended to examine whether the new clinical practice guidelines are improving the percentage of those receiving TRT who actually have an indication for treatment.

Author affiliations: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, F. Edward Hébert School of Medicine, Department of Preventive Medicine & Biostatistics, Bethesda, MD (LCDR Larsen); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Silver Spring, MD (CDR Clausen, Dr. Stahlman)

Acknowledgments: The authors thank the Navy Marine Corps Public Health Center, Portsmouth, VA, for providing laboratory data.

Disclaimer: The contents, views, or opinions expressed in this publication or presentation are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense (DOD), or the Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Lunenfeld B, Mskhalaya G, Zitzmann M, et al. Recommendations on the diagnosis, treatment and monitoring of hypogonadism in men. Aging Male. 2015;18(1):5–15.

- Seftel AD. Male hypogonadism. Part I: Epidemiology of hypogonadism. Int J Impot Res. 2006;18(2):115–120.

- Harman SM, Metter EJ, Tobin JD, Pearson J, Blackman MR. Longitudinal effects of aging on serum total and free testosterone levels in healthy men. Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(2):724–731.

- Bandari J, Ayyash OM, Emery SL, Wessel CB, Davies BJ. Marketing and testosterone treatment in the USA: a systematic review. Eur Urol Focus. 2017;3(4-5):395–402.

- Mulhall JP, Trost LW, Brannigan RE, et al. Evaluation and management of testosterone deficiency: AUA Guideline. J Urol. 2018;200(2):423–432.

- Bhasin S, Brito JP, Cunningham GR, et al. Testosterone therapy in men with hypogonadism: an Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Journal Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2018;103(5):1715–1744.

- Malik RD, Wang CE, Lapin B, Lakeman JC, Helfand BT. Characteristics of men undergoing testosterone replacement therapy and adherence to follow-up recommendations in metropolitan multicenter health care system. Urol. 2015;85(6):1382–1388.

- Walsh TJ, Shores MM, Fox AE, et al. Recent trends in testosterone testing, low testosterone levels, and testosterone treatment among Veterans. Androl. 2015;3(2):287–292.

- Boyle AM. VA educates patients about who really needs testosterone therapy. U.S. Medicine. 31 March 2015. http://www.usmedicine.com/agencies/department-of-veterans-affairs/va-educates-patients-about-who-really-needs-testosterone-therapy/. Accessed 27 Feb. 2019.

- Canup R, Bogenberger K, Attipoe S, et al. Trends in androgen prescriptions from military treatment facilities: 2007 to 2011. Mil Med. 2015;180(7):728–731.

- Basaria S, Coviello AD, Travison TG, et al. Adverse events associated with testosterone administration. NEJM. 2010;363(2):109–122.

- Cole AP, Hanske J, Jiang W, et al. Impact of testosterone replacement therapy on thromboembolism, heart disease and obstructive sleep apnoea in men. BJU Int. 2018;121(5):811–818.

- Naval Medical Aerospace Institute. U.S. Navy Aeromedical Reference and Waiver Guide. https://www.med.navy.mil/sites/nmotc/nami/arwg/pages/aeromedicalreferenceandwaiverguide.aspx. Published 27 Nov. 2018. Accessed 27 Feb. 2019.

- Department of Defense, Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy (ODASD (MC&FP)). 2015 demographics: profile of the military community. http://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2015-Demographics-Report.pdf. Accessed 27 Feb. 2019.