Abstract

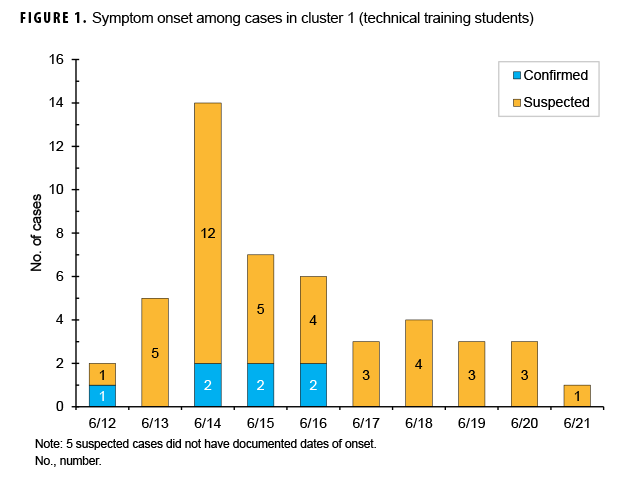

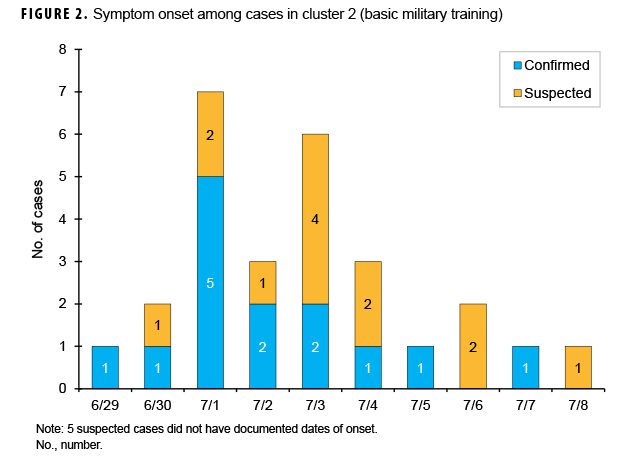

Diarrheal illnesses have an enormous impact on military operations in the deployed and training environments. While bacteria and viruses are the usual causes of gastrointestinal disease outbreaks, 2 Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland, TX, training populations experienced an outbreak of diarrheal illness caused by the parasite Cyclospora cayetanensis in June and July 2018. Cases were identified from outpatient medical records and responses to patient questionnaires. A confirmed case was defined by diarrhea and laboratory confirmation, and patients without a positive lab were classified as suspected cases. In cluster 1, 46 suspected and 7 confirmed cases occurred among technical training students who reported symptom onset from 12 June to 21 June. In cluster 2, 18 suspected and 14 confirmed cases in basic military training trainees reported symptom onset from 29 June to 8 July. Numerous lessons from cluster 1 were applied to cluster 2. Crucial lessons learned during this cyclosporiasis outbreak included the importance of maintaining clinical suspicion for cyclosporiasis in persistent gastrointestinal illness and obtaining confirmatory laboratory testing for expedited diagnosis and treatment.

What Are the New Findings?

Diarrheal disease due to the protozoan Cyclospora cayetanensis had not been previously reported among American military trainees in the U.S. This report describes the life cycle of the protozoan and highlights the difficult nature of source finding and the importance of clinical suspicion for cyclosporiasis in persistent gastrointestinal illness.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Up to 60% of deployed U.S. troops have reported episodes of diarrhea during their deployment. The main causes of these diarrheal illnesses are bacterial and viral, but C. cayetanensis may cause protracted, relapsing gastroenteritis impacting operational readiness and mission effectiveness. This report shares recommendations for future cyclosporiasis outbreak investigations.

Background

Diarrheal illnesses have an enormous impact on military operations. Historically, up to 60% of deployed U.S. troops have reported episodes of diarrhea during their deployment.1–3 Understandably, diarrheal illness negatively impacts operational readiness and mission effectiveness in deployment locations, as it results in increased health care service use, loss of man-hours, and transient critical shortages.4 However, this negative impact is also readily apparent within the unique environment of military training. Moreover, although the majority of military gastrointestinal outbreaks in both the deployed and training environments have been bacterial (e.g., Escherichia coli) or viral (e.g., norovirus) in origin,5–7 recent outbreaks in the U.S. civilian population as well as an outbreak in military training facilities in El Salvador indicate that the protozoan Cyclospora cayetanensis may also pose a threat.8

C. cayetanensis is a coccidian protozoan parasite that causes protracted, relapsing gastroenteritis known as cyclosporiasis.9 Cyclosporiasis is a waterborne and foodborne illness associated with contaminated water or fresh produce, usually imported. The illness has an average incubation period of 7 days, and symptoms can last up to 6 weeks. Excreted oocysts require 1 to 2 weeks outside the human host to undergo sporulation before becoming infectious9; therefore, person-to-person transmission is unlikely. While the course of illness can be self-limited, treatment with trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole can shorten the duration of illness and oocyte excretion.9

From 2000 through 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) tracked 33 U.S. outbreaks of cyclosporiasis.10 In 2017, CDC received notification of 1,065 laboratory-confirmed cases of cyclosporiasis from 40 states, including cases associated with international travel.11 This report describes an outbreak of diarrheal disease caused by C. cayetanensis among U.S. military technical school students (cluster 1) and basic military trainees (cluster 2) at Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland (JBSA–Lackland), TX, during June and July 2018. These outbreaks were unrelated to the 2 national outbreaks of cyclosporiasis that occurred during the same time period.

Methods

Setting

JBSA–Lackland is the only location for U.S. Air Force basic military training (BMT). Recruits come from all parts of the U.S. and from numerous international locations for 7.5 weeks of BMT. At any given time, there are 5,000 to 8,000 BMT trainees distributed across 6 training squadrons. The squadrons are divided into 40- to 50-member training flights. Members of each flight share a common dormitory room and perform all training activities as a unit. Contact between trainees of differing flights is limited to shared common touch surface areas in the Dining Facilities Administration Center (DFAC), classroom hallways, and stairwells. All meals are eaten in DFACs except for a prepackaged meal upon arrival to JBSA–Lackland and meals during the last week of training, when off-base privileges are granted.

Medical care for trainees is provided at the Reid Health Services Center during regular business hours or at the Family Emergency Center at Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center after hours. On average, 2 to 3 trainees per day present to Reid Health Services Center with nausea, vomiting, and/or diarrhea.

Case identification

Cases were identified from review of outpatient medical records from Reid Health Services Center and administered questionnaires. In cluster 1 (technical trainees), 2 teams with reported cases were administered an open-ended questionnaire, and in cluster 2 (BMT trainees), the flight with the greatest number of confirmed cases was administered a questionnaire that gathered information about fresh vegetables and fruits known to have been consumed during training.

For the purposes of this outbreak investigation, a confirmed case of cyclosporiasis was defined by the presence of diarrhea with or without vomiting between 12 June and 8 July 2018 accompanied by a positive gastrointestinal pathogen polymerase chain reaction (PCR) for Cyclospora in a stool specimen. Without a positive lab, a case was classified as a suspected case. Bivariate analysis was carried out to determine whether associations existed between food exposures and illness. Statistical analysis was performed using OpenEpi v3.01.12 One-tailed p values <.01 were considered statistically significant.

Results

Two distinct clusters of cyclosporiasis cases occurred between 12 June and 8 July 2018. Cluster 1 (n=53) occurred among technical training students who reported with symptoms from 12 June through 21 June and included 46 suspected and 7 confirmed cases (Figure 1). Five of the suspected cases did not have documented onset dates. Diarrhea was reported by 100% of cluster 1 cases, with 45% reporting vomiting, and 64% reporting nausea (data not shown). Cluster 2 (n=32) occurred among BMT trainees and included 18 suspected and 14 confirmed cases who reported symptom onset between 29 June and 8 July (Figure 2). Of the 18 suspected cases, 5 cases did not have documented onset dates. In this cluster of 32 cases, 100% reported diarrhea, 44% reported vomiting, and 72% reported nausea (data not shown). One additional confirmed BMT case was reported, but it did not occur in the timeframe of either cluster and was not considered in the analysis.

In cluster 1, the first technical student sought medical care on 13 June for diarrhea; 3 additional students followed on 14 June, and 7 followed on 15 June. The earliest report of symptom onset was on 12 June. At this point, a gastrointestinal disease cluster was suspected in 2 technical training squadrons and gastrointestinal pathogen panel PCRs were ordered. One stool sample was returned to the clinic for testing and tested positive for Cyclospora on 19 June. The next positive Cyclospora PCR was reported on 21 June. One suspected case tested positive for Salmonella. Reported symptom onset peaked 14 June and continued through 21 June (Figure 1). In addition to identifying cases in the clinic, investigators conducted mass briefings from 22 June through 28 June, during which questionnaires were administered to members of 2 technical squadrons to elicit information on food and water exposures. However, data obtained from this open-ended questionnaire lacked the specificity needed to examine associations between exposures to potential food sources and illness.

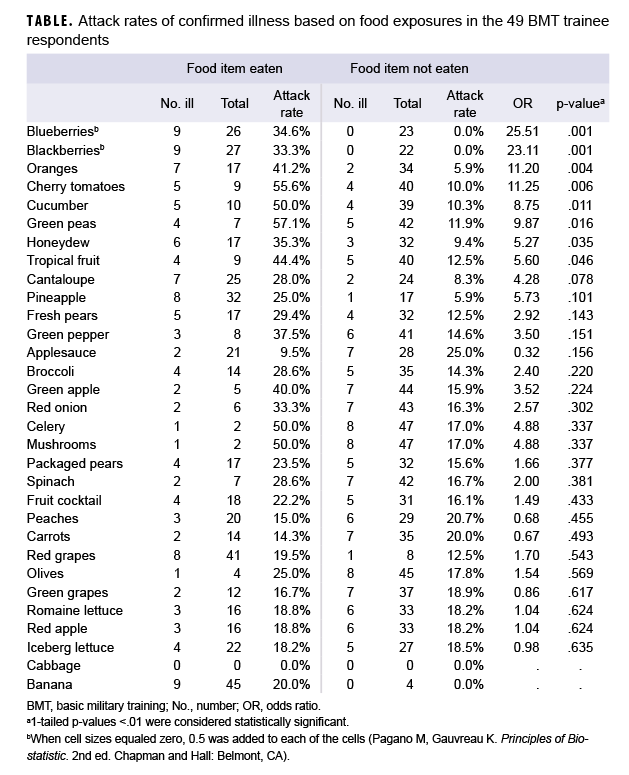

In cluster 2, the first trainee sought medical care on 30 June, and 5 more trainees sought care on 2 July; the earliest report of symptom onset was on 29 June. Gastrointestinal pathogen panel PCRs were already being ordered on all patients with gastrointestinal symptoms visiting the clinic. Three positive Cyclospora PCRs were reported on 3 July, 2 of which belonged to 1 flight. Reported symptom onset peaked on 1 July and continued through 8 July (Figure 2). On 6 July, questionnaires were administered to the trainees in the flight with the most laboratory-confirmed cyclosporiasis cases (n=6). The questionnaire captured information on the fresh food items eaten after arrival at San Antonio, TX. Among the 49 trainees who responded to the BMT questionnaire, 2 additional suspected cases were identified. None of the suspected or confirmed cases from this flight reported departing from the Midwest states that were experiencing a contemporaneous cyclosporiasis outbreak (i.e., IA, IL, MN, and WI). Bivariate analysis of data from the 49 questionnaire respondents demonstrated statistically significant positive associations between confirmed cases and 4 exposures: blueberries (odds ratio [OR]=25.51; p=.001), blackberries (OR=23.11; p=.001), cherry tomatoes (OR=11.25; p=.006), and oranges (OR=11.20; p=.004) (Table 1). No statistically significant associations were identified between other possible food exposures and illness.

Public health investigations were performed at training facilities and DFACs. No DFAC food workers who served confirmed cases reported illness during the outbreak. During inspections of the DFACs, there were no discrepancies noted with respect to Cyclospora. Food vendors that service all DFACs at JBSA–Lackland were questioned, and no concerns other than this outbreak were brought to investigators' attention.

Editorial Comment

During the months of June and July 2018, JBSA–Lackland experienced 2 clusters of cyclosporiasis affecting 2 technical training squadrons and (primarily) 1 BMT flight. Investigations of these clusters did not reveal a specific source of infection; therefore, at the time of the outbreak, there were no known connections to the larger national outbreaks related to Del Monte Fresh Produce vegetable trays or salads from McDonald's restaurants distributed by Fresh Express that were contemporaneously occurring.13,14 At the time of this publication, there were no further confirmed cases of cyclosporiasis in the JBSA–Lackland training population.

Similar to many CDC-reported cyclosporiasis outbreaks, even though there were statistically significant associations with some food items (i.e., blueberries, blackberries, oranges, and cherry tomatoes), a source of the pathogen could not be conclusively determined despite a 2-week food history questionnaire, detailed interviews, and DFAC inspections.10 Potable water and DFAC food from shared sources serve all of the training and permanent populations on JBSA–Lackland. Yet these clusters of cyclosporiasis were restricted to a few specific squadrons and flights. Because of the restricted nature of the outbreak, source exposure was presumed to be most likely through a contaminated batch of produce, and therefore potable water sources were not examined.

Lessons from the investigation response to cluster 1 were implemented in cluster 2. For example, the questionnaire used during cluster 1 did not have enough granularity to determine food associations; therefore, during cluster 2, the investigative team designed a questionnaire based on DFAC menus. Outbreak response also shifted from an early emphasis on treatment to confirmatory testing, providing more accurate case counts and distinction of gastroenteritis due to other potential pathogens (e.g., Salmonella). Lastly, the emphasis on diagnostic testing during cluster 2 resulted in fewer courses of antimicrobial treatment for presumptive diagnoses of cyclosporiasis.

Despite unique opportunities during the investigation of cluster 2 (e.g., control of food and a known cohort), no definitive source of infection was found. The typically long incubation period for cyclosporiasis and delays between symptom onset and diagnosis confirmation represented challenges to identifying the Cyclospora source. In addition, food recall was likely low, even with a comprehensive questionnaire listing fresh food from the DFAC. Even though specific foods were identified, food testing was not feasible because of the short shelf life and immediate use of fresh foods. Moreover, given that Cyclospora has relatively recently emerged in the U.S. (outbreaks have only been reported since the 1990s),10 clinical suspicion of this uncommon parasite as a cause for acute gastrointestinal illness is low. Testing posed another challenge; Cyclospora was not a component of routine ova and parasite testing and had to be requested specifically. Therefore, providers relied on molecular methods in diagnosing cyclosporiasis, and at the onset of the outbreak, the local supplies of testing kits were quickly depleted. Perhaps the most important challenge in determining the source of the outbreak was the low case numbers, which prevented conclusive determination of a source despite observed associations with blueberries, blackberries, cherry tomatoes, and oranges.

The JBSA–Lackland Public Health Flight and Preventive Medicine team collaborated with county, state, and national agencies and shared lessons learned. Perhaps the most crucial lessons learned were the importance of clinical suspicion for cyclosporiasis in persistent gastrointestinal illness and the importance of confirmatory laboratory testing for expedited diagnosis and treatment.

Author affiliations: Trainee Health Surveillance, 559th Medical Group, JBSA–Lackland, TX (Maj Pawlak, Maj Gottfredson); Public Health Flight, 559th Medical Group, JBSA–Lackland, TX (Lt Col Cuomo); 559th Medical Group, JBSA–Lackland, TX (Lt Col White)

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or policy of the Department of Defense or its components.

References

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Gould P, et al. Diarrheal illness among deployed U.S. military personnel during Operation Bright Star 2001—Egypt. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2005;52(2):85–90.

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Riddle MS, Tribble DR. Military importance of diarrhea: lessons from the Middle East. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2005;21(1):9–14.

- Monteville MR, Riddle MS, Baht U, et al. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among deployed US military personnel in support of Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;75(4):762–767.

- Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Frankart C, et al. Impact of illness and non-combat injury during Operations Iraqi Freedom and Enduring Freedom (Afghanistan). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;73(4):713–719.

- Bohnker BK, Thornton S. Explosive outbreaks of gastroenteritis in the shipboard environment attributed to norovirus [Letter to the Editor]. Mil Med. 2003;168(5):iv.

- Riddle MS, Smoak BL, Thornton SA, Bresee JS, Faix DJ, Putnam SD. Epidemic infectious gastrointestinal illness aboard U.S. Navy ships deployed to the Middle East during peacetime operations—2000–2001. BMC Gastroenterol. 2006;6(9).

- Riddle MS, Sanders JW, Putnam SD, Tribble DR. Incidence, etiology, and impact of diarrhea among long-term travelers (US military and similar populations): a systematic review. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2006;74(5):891–900.

- Kasper MR, Lescano AG, Lucas C, et al. Diarrhea outbreak during U.S. military training in El Salvador. PloS One. 2012;7(7):e40404.

- Ortega YR, Sanchez R. Update on Cyclospora cayetanensis, a food-borne and waterborne parasite. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23(1):218–234.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. U.S. Foodorne Outbreaks of Cyclosporiasis—2000–2016. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/foodborneoutbreaks.html. Accessed 24 Sept. 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cyclosporiasis Outbreak Investigations—United States, 2017. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2017/index.html. Accessed 24 Sept. 2018.

- Sullivan KM, Dean A, Soe MM. OpenEpi: a web-based epidemiologic and statistical calculator for public health. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(3):471–474.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate Outbreak of Cyclosporiasis Linked to Del Monte Fresh Produce Vegetable Trays—United States, 2018: Final Update. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2018/a-062018/index.html. Accessed 24 Sept. 2018.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Multistate Outbreak of Cyclosporiasis Linked to Fresh Express Salad Mix Sold at McDonald's Restaurants—United States, 2018: Final Update. https://www.cdc.gov/parasites/cyclosporiasis/outbreaks/2018/b-071318/index.html. Accessed 24 Sept. 2018.