Abstract

During 2001–2018, there were approximately 1.38 million incident diagnoses of myopia, 1.21 million incident diagnoses of astigmatism, and 492,000 incident diagnoses of hyperopia among active component service members (crude overall incidence rates of 7.8, 6.6, and 2.2 diagnoses per 100 person-years, respectively). Incidence rates of all 3 conditions were higher among women compared to men. Service members in the Marine Corps, enlisted personnel, and those working in other/unknown military occupations had higher overall rates of incident myopia diagnoses compared to their respective counterparts. Incidence rates of astigmatism diagnoses were similar across all services and among both enlisted personnel and officers. Overall rates of hyperopia diagnoses were similar across all race/ethnicity groups and service branches and among both enlisted personnel and officers. However, across occupational groups, overall rates of hyperopia and astigmatism diagnoses were highest among service members working in health care occupations. Future analyses should focus on the specific effects of military refractive surgery programs on the readiness of service members.

What Are the Findings?

This article updates previous reports and focuses on the types of refractive error amenable to refractive surgery interventions. During 2001–2018, myopia and astigmatism were the most common refractive errors at 1.4 million and 1.2 million incident diagnoses, respectively, among active component service members of all occupational groups. The crude annual lifetime prevalence was 38.5% for myopia and 32.9% for astigmatism.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Disorders of refraction directly affect the ability to function in a military environment. Myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia remain a consistent concern for the operational force. The data presented here allow for ongoing monitoring of refractive error to direct interventions such as refractive surgery.

Background

Refractive errors are a common cause of impaired vision. The World Health Organization estimates that 153 million people worldwide live with visual impairment due to uncorrected refractive errors.1Refractive errors occur when the focusing power of the eye does not allow for a sharp image on the retina, resulting in a blurred image and loss of detail. Myopia typically results from a longer axial length of the eye, causing images to be defocused in front of the retina and faraway objects to appear blurry. Hyperopia is usually due to a shorter axial length of the eye, causing an image to be defocused at a point behind the retina and resulting in distant objects being seen more clearly than objects that are near. Astigmatism typically results from variable curvature of the corneal surface, causing an image to be defocused along multiple points of the optical pathway.

Optimal visual performance in the setting of refractive error usually requires correction, either through eyeglasses, contact lenses, or refractive surgery. Uncorrected refractive errors can negatively affect functioning, quality of life, and work productivity.2 Refractive errors have been linked to increased ocular morbidity; for example, myopia is a known risk factor in the development of retinal detachment, even at low levels of refractive error.3

Across military populations, refractive errors have multiple implications for readiness and operational effectiveness. Suboptimal visual acuity due to refractive error has been shown to affect target discrimination (positive identification) and marksmanship performance among military personnel.4 Effects of refractive error on visual performance and associated ocular disease increase with higher degrees of refractive error. As a result, individuals with hyperopia, myopia, or astigmatism in excess of -8.00 or +8.00 diopters spherical equivalent, astigmatism in excess of 3.00 diopters, or a history of laser refractive surgery for that degree of refractive error do not meet the medical standards for appointment, enlistment, or induction into U.S. military service.5

In military populations, adequate characterization of the magnitude and trends of refractive errors may inform readiness and performance enhancement efforts such as refractive surgery programs. Adequate characterization may also inform planning for refraction and optical fabrication resources. In this report, myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia codes were chosen to approximate the clinically important refractive error categories used in previous publications.6 For military populations, these categories would also be the most relevant since these conditions are potentially amenable to refractive surgery procedures. This report updates the incidence and prevalence rates of newly diagnosed disorders of refraction among members of the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces during 2001–2018.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2001 to 31 Dec. 2018. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active component of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. Diagnoses of disorders of refraction were ascertained from records maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) that document outpatient encounters of active component service members. Such records reflect care in fixed military treatment facilities of the Military Health System (MHS) and in civilian sources of health care underwritten by the Department of Defense (DOD).

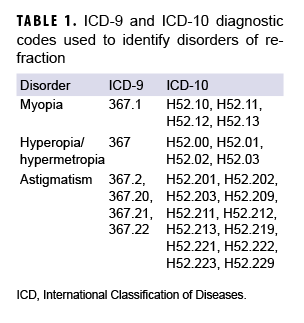

Case-defining diagnoses are shown in Table 1. Cases of myopia, hyperopia, and astigmatism were analyzed separately. An incident case of refraction disorder was defined by at least 1 outpatient medical encounter with a qualifying diagnosis in either the first or second diagnostic position. The incidence date was considered the date of the first qualifying outpatient encounter and an individual was counted as an incident case only once per lifetime. Service members with case-defining refractive disorder diagnoses before the start of the surveillance period (i.e., prevalent cases) were excluded from the analysis. For the incidence rate calculations, person-time at risk included all active component military service time before the date of incident diagnosis, termination of military service, or the end of the surveillance period, whichever came first. Incidence rates were calculated as incident refractive disorder diagnoses per 100 person-years (p-yrs).

Military lifetime prevalence was estimated for each refraction disorder for each year in the surveillance period. During each year of the 18-year period, the annual prevalence was calculated as the percentage of service members who had ever been diagnosed with the refraction disorder. An individual was identified as a prevalent case during a given year of the surveillance period if he or she was in active component service on 1 July of the given year and was diagnosed as an incident case on or before 1 July of that year (including those who were diagnosed as an incident case before the start of the surveillance period). The denominator for annual prevalence calculations consisted of the total number of service members in active component service on 1 July of each year. Annual prevalence estimates were calculated as the number of prevalent cases per 100 active component service members on 1 July.

Results

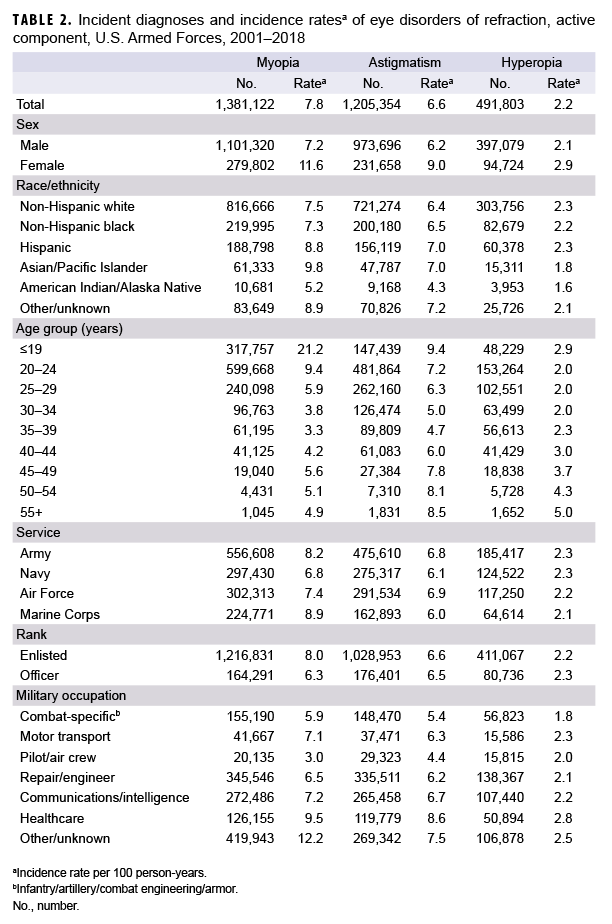

Between 2001 and 2018, there were approximately 1.38 million incident diagnoses of myopia, 1.21 million incident diagnoses of astigmatism, and 492,000 incident diagnoses of hyperopia among active component service members, which corresponded to crude (unadjusted) overall incidence rates of 7.8, 6.6, and 2.2 diagnoses per 100 p-yrs, respectively (Table 2).

For myopia, overall incidence was higher among females (11.6 per 100 p-yrs) compared to males (7.2 per 100 p-yrs). When stratified by age group, the overall rate of incident myopia diagnoses was highest among service members aged 19 years or younger (21.2 per 100 p-yrs) (Table 2). Compared to other race/ethnicity groups, Asian/Pacific Islanders had the highest overall incidence of myopia diagnoses (9.8 per 100 p-yrs) and American Indians/Alaska Natives had the lowest (5.2 per 100 p-yrs) (Table 2). Service members in the Marine Corps (8.9 per 100 p-yrs), enlisted personnel (8.0 per 100 p-yrs), and those working in other/unknown military occupations (12.2 per 100 p-yrs) had higher overall rates of incident myopia diagnoses compared to their respective counterparts. The high rate for those in the non-specific category of "other/unknown" was largely due to the fact that 45% (n=187,536) of the cases were among recruit trainees.

Overall incidence of astigmatism diagnoses was highest among females (9.0 per 100 p-yrs) and those in the youngest (19 years and younger: 9.4 per 100 p-yrs) and oldest (55+ years: 8.5 per 100 p-yrs) age groups (Table 2). Overall rates of incident astigmatism diagnoses were lowest among American Indian/Alaska Native service members (4.3 per 100 p-yrs) and similar among service members in the other race/ethnicity groups (range: 6.4–7.2 per 100 p-yrs). Incidence rates of astigmatism diagnoses were similar across all services and among both enlisted personnel and officers. However, across occupational groups, overall rates of incident astigmatism diagnoses were highest among service members working in health care (8.6 per 100 p-yrs).

For hyperopia, overall incidence was higher in females (2.9 per 100 p-yrs) compared to males (2.1 per 100 p-yrs) and highest among those in the oldest age group (aged 55 years and older: 5.0 per 100 p-yrs). Overall rates of hyperopia diagnoses were similar across all race/ethnicity groups, service branches, and among both enlisted personnel and officers. However, overall incidence of this condition was highest among service members in health care occupations (Table 2).

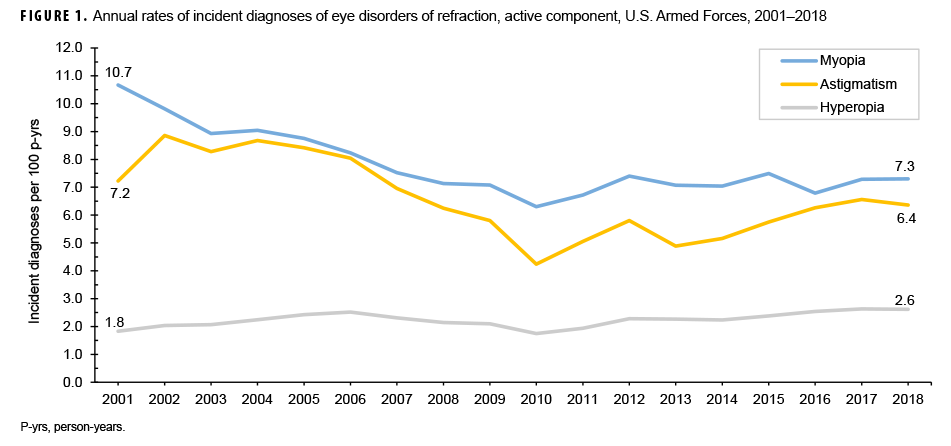

Crude annual rates of incident diagnoses of myopia and astigmatism decreased 40.9% and 41.3%, respectively, between 2001 and 2010. Incidence rates then increased 15.9% and 50.0% for myopia and astigmatism, respectively, between 2010 and 2018 (Figure 1). The crude annual incidence of hyperopia diagnoses increased slightly over the course of the surveillance period, from 1.8 per 100 p-yrs in 2001 to 2.6 per 100 p-yrs in 2018.

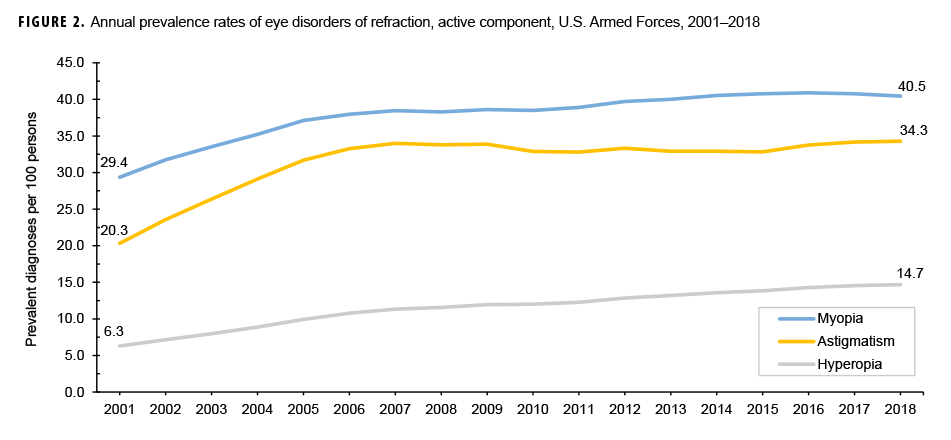

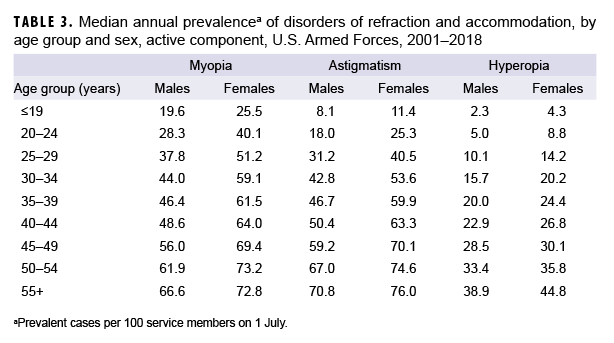

During the 18-year surveillance period, the median crude annual prevalence was 38.5% for myopia, 32.9% for astigmatism, and 12.0% for hyperopia (data not shown). In both sexes, the median crude annual lifetime prevalence of each type of eye disorder of refraction increased with increasing age (Table 3). For myopia and astigmatism, crude annual prevalence rates increased markedly between 2001 and 2007 before leveling off and remaining relatively stable for the remainder of the surveillance period (Figure 2). In contrast, crude annual prevalence rates of hyperopia increased gradually over the course of the surveillance period.

Editorial Comment

This report demonstrates the high frequency of myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia among active component service members across all subgroups examined. Results of the current analysis were consistent with findings of the previous MSMR report.6 Analysis of vision examination data from the 1999–2004 U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) yielded age-adjusted point prevalence estimates of myopia, astigmatism, and hyperopia of 33.1%, 36.2%, and 3.6%, respectively.7 The prevalence of hyperopia was considerably higher in the current analysis. However, the current analysis measured lifetime prevalence whereas the NHANES measured point prevalence (i.e., the percentage of the U.S. population with current hyperopia).7

The impact of refractive error on military members can be different than on other populations. Military personnel have defined and demanding physical performance criteria. Service members are frequently classified as "tactical athletes" because of high physical performance demands under stressful conditions often in austere environments.8 Refractive error, even when corrected, has been shown to negatively affect both depth perception and peripheral vision in young athletes.9 Many athletes will prefer either use of contact lenses or refractive surgery over eyeglasses.10

Certain limitations should be considered when interpreting the findings of this report. First, service members are, in many respects, not representative of the general U.S. civilian population. Because service members have been screened for disorders of refraction before joining the military, the visual disorders diagnosed among them do not include the most severe conditions. In addition, refractory surgery among the general civilian population has become more common, and candidates for military service may elect to have refractive surgery before entering service. This could decrease the incidence and prevalence of refractive error over time. Further analysis is planned to specifically evaluate the incidence and temporal trends of refractive error among the recruit trainee population. Such an analysis may provide better insight into the incidence of refractive error among individuals entering the military during the surveillance period.

Refractive surgery procedures after entering the military may also influence the prevalence of refractive errors. For example, a recent report showed that the number of refractive procedures (both photorefractive keratectomy [PRK]/laser epithelial keratomileusis [LASEK] and laser-assisted in-situ keratomileusis [LASIK]) among active component service members averaged 12,157 per year from 2005 through 2014.11 However, the direct impact of refractive procedures among service members on incidence and prevalence of refractive error was not evaluated in this report. Extrapolation of the findings of the current analysis to the general U.S. population should be undertaken with this limitation in mind.

The increasing prevalence of hyperopia found in this report may be due to increasing age among the surveillance population. Hyperopia incidence increases over time because of changes in the optical system of the eye associated with aging. However, the current report did not examine the potential change in age among cases of hyperopia during the study period.

Another limitation is related to the new electronic health record for the MHS, MHS GENESIS, which was implemented at several military treatment facilities during 2017. Medical data from sites that are using MHS GENESIS are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounters for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities during 2017–2018 were not included in this analysis.

This analysis did not attempt to ascertain the nature or frequency of any corrective measures of treatments, such as prescriptions for contact lenses or corrective surgery. For active component service members, contact lens use is limited to few operational situations.11 Some aviation personnel require contact lens correction of refractive error for optimal use of instruments. Contact lens use in austere locations has been associated with high risk for microbial keratitis.12 Refractive surgery has been associated with both improved military readiness and vision-related quality of life (including military-specific tasks such as use of night vision goggles and weapons-based tasks).13 However, refractive surgery services are limited by location and necessary prioritization of resources. The correction of refractive errors in U.S. military personnel to optimize their readiness and performance does present some ongoing challenges. Future studies should focus on the specific effects of military refractive surgery programs on readiness of service members.

In addition, because refractive surgery has become very common in the general population, the proportion of incoming recruits with refractive errors may be decreasing over time. A history of refractive surgery is not disqualifying from military service and having had such surgery may not be disclosed at the time of entry into military service or documented in a recruit’s medical records. If the proportion of recruit trainees with (uncorrected) refractive error has been decreasing, then the prevalence across the active component force would decrease over time. Such declining prevalence could affect the refractive surgery programs across the DOD. Future examination of recent trends in the prevalence of refractive disorders among recruits is warranted.

Author affiliations: Department of Defense/Veterans Affairs Vision Center of Excellence, Defense Health Agency Research and Development Directorate (COL Reynolds); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch, Defense Health Agency (Dr. Taubman, Dr. Stahlman)

Disclaimer: The contents, views, or opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Defense Health Agency, Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government.

References

- Resnikoff S, Pascolini D, Mariotti SP, Pokharel GP. Global magnitude of visual impairment caused by uncorrected refractive errors in 2004. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86(1):63–70.

- Schneider J, Leeder SR, Gopinath B, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Frequency, course, and impact of correctable visual impairment (uncorrected refractive error). Surv Ophthalmol. 2010;55(6):539–560.

- The Eye Disease Case-Control Study Group. Risk factors for idiopathic rhegmatogenous retinal detachment. Am J Epidemiol. 1993;137(7)49–57.

- Hatch BC, Hilber DJ, Elledge JB, Stout JW, Lee RB. The effects of visual acuity on target discrimination and shooting performance. Optom Vis Sci. 2009;86(12): e1359–e1367.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Personnel and Readiness. Department of Defense Instruction 6130.03 Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services. 6 May 2018.

- O’Donnell FL, Taubman SB, Clark LL. Incidence and prevalence of diagnoses of eye disorders of refraction and accommodation, active component service members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2014. MSMR. 2015;22(3):11–16.

- Vitale S, Sperduto RD, Ferris FL 3rd. Increased prevalence of myopia in the United States between 1971–1972 and 1999–2004. Arch Ophthalmol. 2009;127(12):1632–1639.

- Sefton JM, Burkhardt TA. Introduction to the Tactical Athlete Special Issue. J Athl Train. 2016;51(11):845.

- Chang ST, Liu YH, Lee JS, See LC. Comparing sports vision among three groups of soft tennis adolescent athletes: normal vision, refractive error with and without correction. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2015;63(9):716–721.

- Zeri F, Pitzalis S, Di Vizio A, et al. Refractive error and vision correction in a general sports-playing population. Clin Exp Optom. 2018;101(2):225–236.

- Blitz JB, Hunt DJ, Cost AA. Post-refractive surgery complications and eye disease, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005–2014. MSMR. 2016;23(5):2–11.

- Musa F, Tailor R, Gao A, Hutley E, Rauz S, Scott RA. Contact lens-related microbial keratitis in deployed British military personnel. Br J Ophthalmol. 2010;94(8):988–993.

- Sia RK, Ryan DS, Rivers BA, et al. Vision-related quality of life and perception of military readiness and capabilities following refractive surgery among active duty U.S. military service members.J Refract Surg. 2018;34(9):597–603.