Abstract

Leprosy, or Hansen's disease (HD), is caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium leprae and is a significant cause of morbidity worldwide. Clinical manifestations range from isolated skin rash to severe peripheral neuropathy. Treatment involves a prolonged course of multiple antimicrobials. Although rare in the U.S., with only 168 new cases reported in 2016, HD remains a prevalent disease throughout the world, with 214,783 new cases worldwide that same year.1 It remains clinically relevant for service members born in and deployed to endemic regions. This report describes a case of HD diagnosed in an active duty soldier born and raised in Micronesia, a highly endemic region.

Case Report

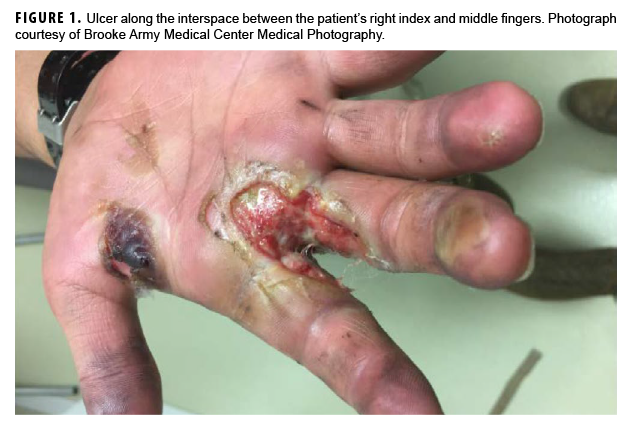

In May 2018, a 21-year-old male soldier presented with right hand swelling and ulcer formation along the interspace between his index and middle fingers while he was deployed to Eastern Europe (Figure 1). He first developed a blister at that site after washing a tank several days earlier, and it subsequently progressed to an ulcer. The ulcer was initially assessed as a third-degree burn, and he was transferred to Brooke Army Medical Center (Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, TX) for management on 11 May 2018. At that time, the patient denied any pain but described gradual loss of sensation to his right hand dating back to Jan. 2018. The patient had been otherwise healthy except for a right hand burn injury during basic training in early 2017, which had completely healed without complications. He denied any close contacts with Hansen's disease (HD). The patient had enlisted in the Army in Jan. 2017 from the Federated States of Micronesia and completed initial entry training in June 2017 at Fort Benning, GA. He completed advanced individual training at Fort Riley, KS, and then was deployed to Europe in Nov. 2017.

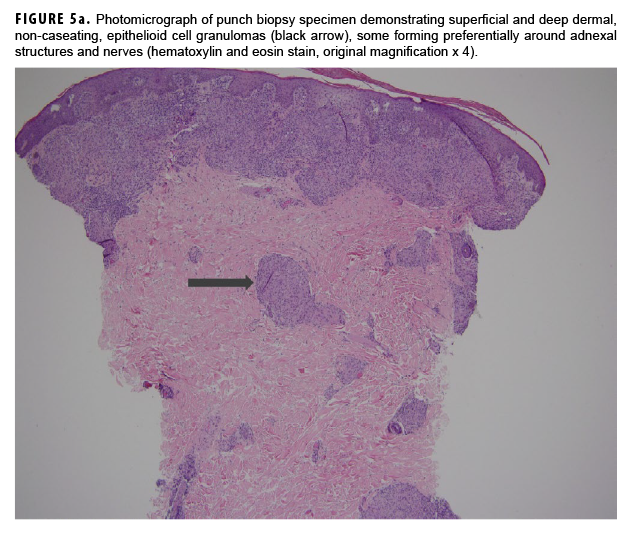

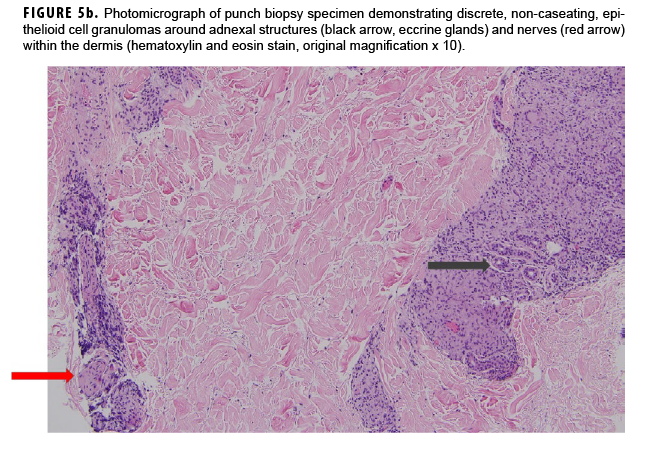

In May 2018, the patient successfully underwent full-thickness skin graft of his ulceration but continued to experience edema and eventually lost intrinsic motor function of his right hand. He remained at Fort Sam Houston, where a nerve conduction study in July 2018 revealed severe median, ulnar, and radial neuropathies in the right forearm. Around that time, the patient noticed eruption of annular, hyperpigmented, erythematous plaques on his right medial arm, which spread to his bilateral limbs and trunk (Figures 2a, 2b). These symptoms coincided with new edema and numbness involving his left hand. In Sept. 2018, magnetic resonance imaging revealed perineural edema involving nerve groups of his distal right arm (Figure 3a, 3b). The patient was referred to dermatology, where examination noted thickening of peripheral nerves, including the greater auricular nerve (Figure 4); a clinical diagnosis of HD was made. Skin biopsy showed tuberculoid granulomas extending along adnexal structures and nerves (Figure 5a, 5b). Fite staining was negative for acid-fast organisms. Polymerase chain reaction testing at the National Hansen's Disease Program (NHDP) was also negative for Mycobacterium leprae. Given his histopathology, edema, and rapid progression of neurologic impairment, the patient was diagnosed with paucibacillary leprosy complicated by type 1 reversal reaction. In consultation with the NHDP, the patient was started on clarithromycin 500 mg daily and minocycline 100 mg daily in Oct. 2018. Prednisone 60 mg daily was started for the patient's type 1 reversal reaction and neuropathy. Steroids were tapered over the ensuing 6 months, while methotrexate 12.5 mg weekly was added as a steroid-sparing agent.

At follow-up in Dec. 2018, the patient showed improvement in the appearance of his skin lesions and the edema in both hands, with some improvement in motor and sensory exam. At follow-up in May 2019, he remained on clarithromycin, minocycline, and methotrexate. He showed further improvement in the appearance of his skin lesions. However, he continued to have persistent right hand weakness and persistent left ulnar neuropathy. He was referred to the medical evaluation board and was discharged from the Army in Aug. 2019.

Editorial Comment

HD is caused by M. leprae. While the disease is endemic in the southern U.S., the majority of cases found here are diagnosed in individuals born outside of the U.S., where exposure is thought to have occurred.2 The Federated States of Micronesia has a high prevalence of HD, and immigrants from Oceanic countries have the highest rates of diagnosis in the U.S.2,3

Skin lesions and peripheral nerve damage are hallmarks of HD. The diagnosis can be made clinically, though histopathology is the gold standard.4 Complications of HD include type 1 reversal reactions, which are associated with increased cell-mediated immune response to M. leprae, leading to increased edema and swelling of peripheral nerves and increased erythema of existing skin lesions.4 This patient's presenting symptoms of hand edema and ulceration (Figure 1) represented a type 1 reversal reaction that led to significant neurologic impairment.

The treatment of HD typically involves dapsone and rifampin, with or without clofazimine, based on the disease classification.5 Minocycline and clarithromycin are bactericidal against M. leprae6 and have been used as alternative treatments when first-line agents cannot be used because of drug intolerance or, as in this case, drug interactions between rifampin and prednisone.4 The treatment of type 1 reversal reaction typically involves corticosteroids, though the overall efficacy and duration of therapy remain uncertain.7,8

The military provides a unique environment for exposure, as soldiers are often deployed into endemic areas. However, reported cases of HD among U.S. military personnel are rare. The first such reported cases occurred in the Spanish-American War (1898) despite prior conflicts in endemic areas.9,10 Among the 323 reported cases of leprosy in veterans between 1920 and 1968, less than 80 were thought to be service related.9 Among those cases not involving infections after receiving tattoos, only 2 cases involved service members whose length of exposure was reported as less than 1 year.9,10 The Vietnam War brought U.S. soldiers into combat in endemic areas of Southeast Asia, but there are even fewer reported cases among veterans of this conflict, with at least 3 service-related cases.11–13 The low number of cases likely reflected decreased exposure time due to shorter deployments and the use of dapsone for malaria prophylaxis.14 Since the start of the current Global War on Terrorism, there have been at least 6 published cases of HD among active duty U.S. military members, the majority of which were not service related.15–18 Five of the 6 published cases involved service members from Micronesia. (Currently, there are 2 other active cases of HD being treated in service members in conjunction with the NHDP.) In a case series of 3 active duty soldiers from Micronesia with HD, the average time to diagnosis was 8 months.15 This observation illustrates that HD's indolent course of skin lesions and neurologic deficits can lead to a delay in diagnosis.19 Given the potential morbidity associated with delayed diagnosis, providers should consider HD in a patient from an endemic region with rash and neuropathy.

There have been no published reports among U.S. troops of HD secondary to exposure to other infected service members. However, there have been reported cases of family members contracting HD from service members.9 Such examples indicate that prolonged, close exposure to an infected individual or prolonged travel to endemic countries is needed for infection with HD.

Before effective therapies were widely available, a diagnosis of HD resulted in discharge from the U.S. Army.9 However, currently, if the HD responds to treatment and does not lead to physical limitations, affected service members may be retained.20

In summary, HD is rare in the U.S. military and its veterans. However, because of the potential significant morbidity associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment of HD, this condition should be considered in patients presenting with skin lesions and peripheral neuropathy, especially if the patients are from HD-endemic regions.

Author affiliations: Brooke Army Medical Center, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam Houston, TX (MAJ Jansen and Maj Lindholm); National Hansen's Disease Program, Baton Rouge, LA (Dr. Stryjewska); Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Maj Lindholm); Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, TX (Maj Bandino and Capt Durso)

Disclaimer: The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Brooke Army Medical Center, Wilford Hall Ambulatory Surgical Center, the U.S. Army Medical Department, the U.S. Army Office of the Surgeon General, the Department of the Army, the Department of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. Mention of trade name, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. The authors are employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17 U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17 U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties.

References

- World Health Organization. Global leprosy update, 2016: accelerating reduction of disease burden. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2017;92(35):501–519.

- Nolen L, Haberling D, Scollard D, et al. Incidence of Hansen's disease—United States, 1994–2011. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2014;63(43):969–972.

- Woodall P, Scollard D, Rajan L. Hansen disease among Micronesian and Marshallese persons living in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17(7):1202–1208.

- Britton WJ, Lockwood DN. Leprosy. Lancet. 2004;363(9416):1209–1219.

- Moschella SL. An update on the diagnosis and treatment of leprosy. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51(3):417–426.

- Ji B, Jamet P, Perani EG, Bobin P, Grosset JH. Powerful bactericidal activities of clarithromycin and minocycline against Mycobacterium leprae in lepromatous leprosy. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(1):188–190.

- Van Veen NH, Nicholls PG, Smith WC, Richardus JH. Corticosteroids for treating nerve damage in leprosy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(5):CD005491.

- Walker SL, Lockwood DN. Leprosy type 1 (reversal) reactions and their management. Lepr Rev. 2008;79(4):372–386.

- Brubaker ML, Binford CH, Trautman JR. Occurrence of leprosy in U.S. veterans after service in endemic areas abroad. Public Health Rep. 1969;84(12):1051–1058.

- Aycock WL, Gordon JE. Leprosy in veterans of American wars. Am J Med Sci. 1947;214(3):329–339.

- Medford FE. Leprosy in Vietnam veterans. Arch Intern Med. 1974;134(2):373.

- Rose HD. Letter: Leprosy in Vietnam returnees. JAMA.1974;230(10):1388.

- Kivirand AI, Price PH. Leprosy in Vietnam veteran. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1979;103(7):367.

- Enna CD, Trautman JR. Leprosy in the military services. Mil Med. 1969;134(12):1423–1426.

- 15. Hartzell JD, Zapor M, Peng S, Straight T. Leprosy: a case series and review. South Med J. 2004;97(12):1252–1256.

- Berjohn CM, DuPlessis CA, Tieu K, Maves RC. Multibacillary leprosy in an active duty military member. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21(6):1077–1078.

- Bossalini JP, Bandino JP, Miletta NR. Delayed diagnosis of leprosy in a Micronesian soldier—case report. Mil Med. 2019;184(9/10):561–564.

- Wellington T, Schofield C. Late-onset ulnar neuritis following treatment of lepromatous leprosy infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2019;13(8):e0007684.

- Chad DA, Hedley-Whyte ET. Case records of the Massachusetts General Hospital. Weekly clinicopathological exercises. Case 1-2004. A 49-year-old woman with asymmetric painful neuropathy. N Engl J Med. 2004;350(2):166–176.

- Headquarters, Department of the Army. Army Regulation 40-501. Medical Services. Standards of Medical Fitness. 27 June 2019.

CE/CME

Information for CE/CME Credit: This activity offers continuing education (CE) and continuing medical education (CME) to qualified professionals as well as a certificate of participation to those desiring documentation. For more information, go to www.health.mil/msmrce.

Method of Participation in CE/CME Activity: The core material for these activities can be read in this issue of the MSMR or online at www.health.mil/msmrce. Individuals seeking credits and certificates must complete both the online test and evaluation after studying the material. The test and evaluation will be available for only 6 months after publication. Fax or other copies will not be accepted.

Date of Original Release: 30 Dec. 2019. Credit may be obtained for these courses until 26 June 2020.

Target Audience: Public health and medical practitioners; epidemiologists and researchers; health care executives, administrators and policy makers.

Accreditation Statement: DHA J7 Continuing Education Program Office (CEPO) is jointly accredited by the Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME), the Accreditation Council for Pharmacy Education (ACPE), the American Nurses Credentialing Center (ANCC), the American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA), the Association of Regulatory Boards of Optometry's Council on Optometric Practitioner Education (ARBO/COPE), the American Psychological Association (APA), and the Association of Social Work Boards (ASWB) to provide continuing education for an array of health care providers. DHA J7 CEPO also provides certificates of attendance that may be used for other licensing boards.

Key points

- Though endemic in the southern U.S., Hansen's disease is rare in the U.S., with most cases diagnosed among immigrants from countries with a higher prevalence of disease. The low prevalence of disease can delay diagnosis, which can lead to significant morbidity.

- Because the causative agent, Mycobacterium leprae, cannot be cultured, diagnosis is based on clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. Skin lesions with diminished sensation accompanied by peripheral neuropathy should raise suspicion for Hansen's disease.

- Prolonged, close contact with infected individuals is required for infection. For service members in the current era of shorter deployments, a diagnosis of Hansen's disease is unlikely to be service related; spread of infection among service members has not been reported.

Learning objectives

- The reader will describe the clinical presentation of Hansen's disease and the need for early diagnosis.

- The reader will identify risk factors associated with contracting Hansen's disease.

- The reader will explain the military relevance of Hansen's disease and historical military-specific risk factors or lack thereof for contracting the infection.

Disclosure of Relevant Financial Relationships with Commercial Interests: MSMR editorial staff engage in a monthly collaboration with the DHA J7 CEPO to provide this CE/CME activity. MSMR staff authors, the DHA J7 CEPO, and the planners and reviewers of this activity have no financial or non-financial interest to disclose. The authors of this article have no competing financial interests or conflicts of interest to disclose.

The information and opinions presented here reflect the views of the authors and should not be construed as reflecting official views, policies, or positions of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.