Abstract

Previous studies have suggested that the use of nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is associated with an increased risk of stress fractures due to their inhibitory effect on bone formation. The current study evaluated the relative risk of stress fractures in active duty service members with and without previous receipt of NSAIDs. A total of 7,036 cases of stress fracture and 28,141 matched controls were identified between June 2014 and Dec. 2018 and included in the analysis. A subset of cases were evaluated for delayed healing diagnoses within 90 days following incident case diagnosis using International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes. Prior receipt of NSAIDs was associated with an increased incidence of stress fractures (adjusted incidence rate ratio=1.70; 95% confidence interval [CI]:1.58–1.82; p<.0001). Among stress fracture cases, prior receipt of NSAIDs was associated with increased diagnosis of delayed healing (adjusted odds ratio=1.41; 95% CI: 1.12–1.77; p=.004). These findings may have significant implications for military readiness because NSAIDs are used extensively and stress fractures are already a major contributor to the burden of health care encounters and lost duty time.

What Are the New Findings?

This is the first MSMR report on the association between prior NSAID receipt and incident stress fracture diagnosis in service members. Prior NSAID receipt was associated with a 70% increased incidence of stress fracture. Among cases, the odds of a delayed healing diagnosis among NSAID recipients were 1.4 times that of nonrecipients.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

This study suggests that receiving NSAIDs may increase the risk for stress fracture among active component service members. These stress fracture injuries may contribute to lost duty days and reduce deployment readiness because of physical limitation.

Background

Service members in the U.S. Armed Forces participate in intense physical activity when training and performing their job responsibilities. The physical activity can potentially result in overuse injuries because the repetitive force exerted by the musculoskeletal system may cause cumulative microtraumatic damage leading to strains, sprains, and stress fractures.1–3 Injuries, including stress fractures, are a major public health concern among the military because of their high prevalence, the associated lost working time, and the cost of treatment. A previous MSMR article estimated that there were 31,349 incident stress fractures diagnosed (a rate of 3.2 per 1,000 person-years) among active component service members from 2004 through 2010.3 A recent study among the Royal Marines during commando training found that, on average, the rehabilitation time for stress fractures ranged from 12 to 21 weeks depending on the site of fracture.4 The burden associated with stress fractures is high when taking into consideration the incidence rate, slow recovery time, and medical cost of treatment.

Hughes and colleagues examined the association between stress fractures and nonsteroidal anti inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) in a U.S. Army population and found that both NSAIDs and acetaminophen potentially increase the risk for stress fractures.2 If NSAID use is associated with an increase in stress fracture risk, this finding could have a sizable impact on military readiness given the widespread use of these drugs. In 2014, approximately 82% (n=418,579) of active duty U.S. Army service members filled at least 1 NSAID prescription.5 Many service members could be unknowingly increasing their risk for stress fractures by taking medications to decrease the pain and swelling associated with other physical complaints.

The use of NSAIDs to treat swelling and pain from fractures has been widely debated. Studies have claimed that NSAIDs could increase the risk of a fracture or delay the healing of a fracture because of the drug's inhibitory effect on bone metabolism.2,6–10 In theory, this claim is plausible when considering the impact of the mechanism of action for NSAIDs on the physiological process of bone metabolism. Bone metabolism involves osteoclasts and osteoblasts, which are responsible for the removal of bone and the growth of bone, respectively.9–12 Bone metabolism can be grouped into 2 processes: bone modeling and bone remodeling.10,11 During bone modeling, there is bone formation on the surface of bones in response to mechanical loading.10,11 The loading initiates osteoclast-mediated biochemical signaling and Wnt/ß-catenin pathway activation, which are crucial for osteoblast differentiation, proliferation, and bone formation.10 During bone remodeling, there is bone resorption and then bone formation to replace old or damaged bone.10,11 During remodeling, osteoclasts remove the area of damaged bone and osteoblasts then replace it with new bone. However, the new bone is temporarily more porous, and in turn, more fragile and injury prone.10

Bone metabolism can be both stimulated and inhibited by a group of physiologically active lipid compounds called prostaglandins, which are responsible for the differentiation of osteoclasts and osteoblasts as well as resorbing activity of mature osteoclasts.9,10,12,13 There are 2 initiators to the production of prostaglandins: cyclooxygenase-1 (COX-1) enzyme and cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) enzyme. COX-1 produces prostaglandins in response to physiological conditions such as tissue homeostasis and cell-to-cell signaling, while COX-2 produces them in response to inflammation.9,10,12,14 NSAIDs inhibit the activity of COX by competing with arachidonic acid for binding to the enzyme.9,12 Therefore, NSAIDs reduce the production of prostaglandins, limiting the differentiation of osteoclasts and osteoblasts and the resorbing activity of osteoclasts, which then inhibits bone resorption and formation. In theory, this inhibition could interfere with bone modeling and remodeling and increase the risk of fracture or delayed healing. Studies have shown that the timing of NSAID use is key to the inhibition of bone modeling.10,15–17 Bone formation is suppressed if NSAIDs are taken before bone loading, but not if NSAIDs are taken afterwards.10,15–17

NSAIDs can be categorized by their inhibiting effect on the COX enzymes. Each class of NSAID is selective to binding to COX enzymes with varying degrees. The nonselective COX inhibitors impede the activity of both COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes with no discrimination.14 Preferentially selective COX-2 inhibitors impede COX-2 activity at lower drug concentrations, but there is some COX-1 inhibition at label dose. Selective COX-2 inhibitors (coxibs) impede COX-2 activity but not COX-1 at label dose.14 Studies have indicated a negative effect of NSAIDs on the bone healing process because NSAIDs limit osteogenesis and angiogenesis through blocking COX-2.14,18–20 However, NSAIDs have other mechanisms that can impair healing from a bone injury. Besides limiting osteogenesis and angiogenesis, NSAIDs can initiate apoptosis, alter collagen content and fiber size, and modify genes produced from a signaling pathway that plays a role in differentiation and proliferation of osteoblast precursor cells.14,21

Some animal studies have provided evidence that bone repair is either delayed or impaired by NSAID treatment and that the degree of delay in bone healing depends on the type of fracture and type of NSAID prescribed.7,11,22 Human studies examining the effect of NSAIDs on fracture healing have observed inconsistent results. A retrospective study of patients with tibia fractures found that patients taking any NSAIDs were more likely to have delayed healing compared to those patients not taking any NSAIDs.7,23 In addition, a retrospective analysis examining healing from a fracture of the femur diaphysis found that there was an association between nonunion and use of NSAIDs after injury.7,24 This study also identified patients who, although their fractures had united, showed a delay in healing after taking NSAIDs.7,24 In contrast, a double-blind randomized study examined healing from Colles fractures after treating postmenopausal women with either piroxicam or placebo and found no statistically significant delay in healing with the NSAID treatment.7,25

Although it has been suggested that NSAIDs may increase risk for fractures and delay bone repair, the findings from studies on such topics have been mixed. The objective of this study was to estimate the risk of stress fracture following receipt of NSAIDs among active component military service members between June 2014 and Dec. 2018. In addition, the current study evaluated the association between NSAID receipt and International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) coded diagnosis of delayed healing among incident stress fracture cases.

Methods

The eligible study population consisted of active component service members in the Army, Air Force, Navy, or Marine Corps who served for any length of time between 1 June 2014 and 31 Dec. 2018. This study period was selected based on the availability of pharmacy data in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). All study data were derived from the DMSS, a relational database maintained by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Multiple data sources feed information into the DMSS, forming tables related to demographic characteristics, prescriptions dispensed, and administrative health records. Pharmacy data in the DMSS are derived from the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS), which has information on outpatient prescriptions dispensed by mail order, at military treatment facilities (MTFs), by Veterans Affairs for dual eligible beneficiaries, and at civilian facilities if billed through TRICARE. The medical encounters in the DMSS contain records of both hospitalizations and ambulatory visits in fixed MTFs and civilian treatment facilities billed through TRICARE.

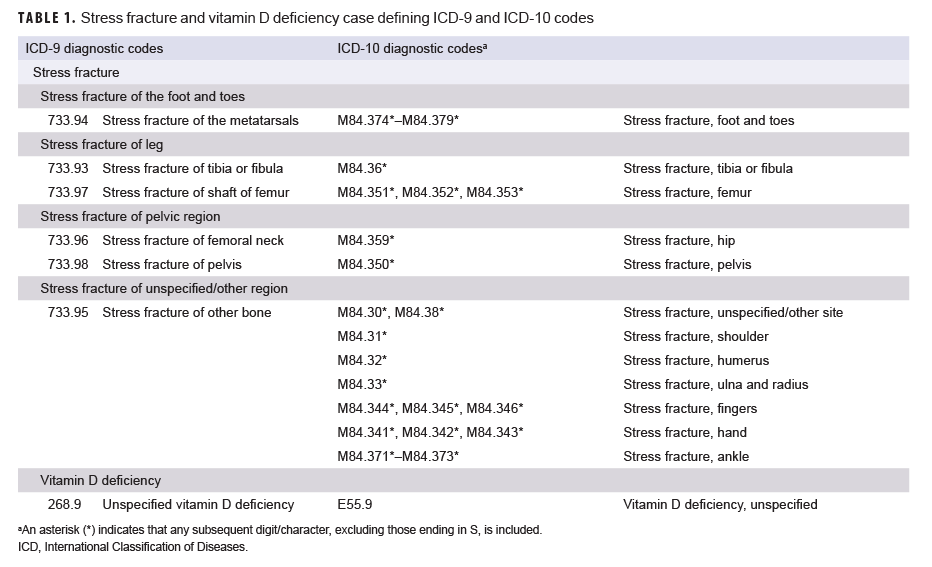

To qualify as an incident case of stress fracture, an individual had to have either 1) an outpatient medical encounter with a qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis code for stress fracture (Table 1) in any diagnostic position followed by another outpatient medical encounter for a diagnosed stress fracture within 14 to 90 days later or 2) a hospitalization with a diagnosis code for stress fracture in any diagnostic position. The incidence date, also referred to as reference date for controls, was the date of the first qualifying encounter. If there was a hospitalization and an outpatient encounter on the same day, then inpatient records were prioritized over outpatient encounters. If the first encounter occurred before the surveillance period, the service member was considered a prevalent case and was excluded from the analysis. An individual could be counted as an incident case only once per lifetime. Those who had any outpatient diagnoses of stress fracture during their military service before the first qualifying encounter were excluded.

The first part of the study employed a case-control design with risk-set matching to assess the association between prescribed NSAID and incident stress fracture diagnosis among active component service members from June 2014 through Dec. 2018. Up to 4 controls were matched to each case based on sex, race/ethnicity, service branch, age (within 1 year), and time in service category. Random selection was performed if more than 4 controls were matched to a case. Race/ethnicity was coded as non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian/Alaska Native, and other/unknown. Time in service was categorized as less than 4 months, 4 months to less than 1 year, 1 year to less than 2 years, 2 years to less than 5 years, and 5 years or more. Controls were allowed to be matched to multiple cases if they fit the matching criteria and were able to become a case later in the study. Controls with any diagnosis of a stress fracture in an inpatient or outpatient encounter on or before the reference date were excluded from being a control for that match.

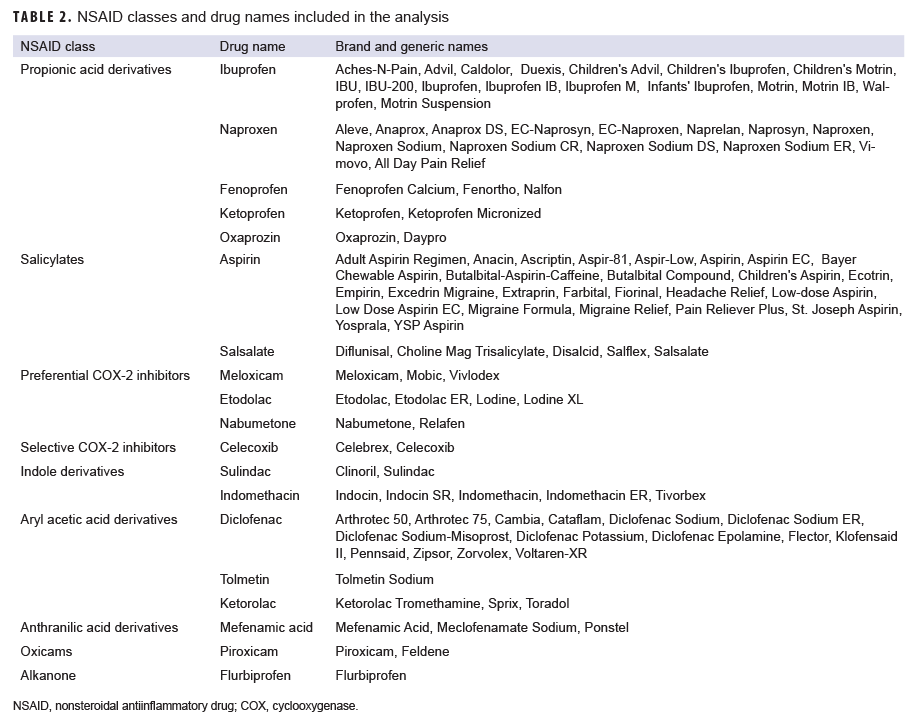

To measure exposure, prescription records were included in the analysis if the records contained an American Hospital Formulary Service (AHFS) therapeutic class code for NSAID (280804) and the drug (brand or generic) name (Table 2). An individual was considered exposed to an NSAID if the prescription date was 30 to 180 days before the reference date. NSAID use within 30 days before the reference date was not considered a qualifying exposure in order to avoid the potential effects of reverse causation from the use of prescribed NSAIDs to treat the pain of a pre-clinical stress fracture.2 Service members could be exposed to multiple NSAIDs during the 30-to 180-day exposure period, and indicator variables were created to identify the different NSAID classes.

Vitamin D deficiency was included in the analysis as a potential confounding factor since several studies have suggested that this deficiency is related to both NSAID use and stress fractures.26–29 For this study, a case of vitamin D deficiency was defined as having a hospitalization or ambulatory encounter with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 diagnosis code for vitamin D deficiency in any diagnostic position within 1 year before to 6 months following the reference date (Table 2).

The study secondarily assessed the association between NSAID receipt and diagnosis of delayed healing among the subset of incident stress fracture cases identified during the period between Oct. 2015 and Dec. 2018. A case was considered delayed healing if there was an ICD-10 diagnosis code beginning with "M843" (stress fracture) and ending in "G" (subsequent encounter for fracture with delayed healing) recorded during an inpatient or outpatient encounter within 90 days of the incident stress fracture diagnosis.

For the first part of the study, adjusted incidence rate ratios and associated 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated using a multivariable logistic regression model to estimate the effect of NSAID receipt on incident stress fracture diagnosis. The model adjusted for sex, race/ethnicity, service, age, time in service, recruit status, occupation, and diagnosis of vitamin D deficiency. The same adjusted incidence rate ratio was calculated for just the Army population. For the second part of the study, adjusted odds ratios and associated 95% CIs were calculated using multivariable logistic regression to estimate the effect of NSAID receipt on delayed healing diagnosis among stress fracture cases. Covariates adjusted for in the model were age, sex, race/ethnicity, vitamin D deficiency, time in service, service branch, military occupation, and recruit status.

Results

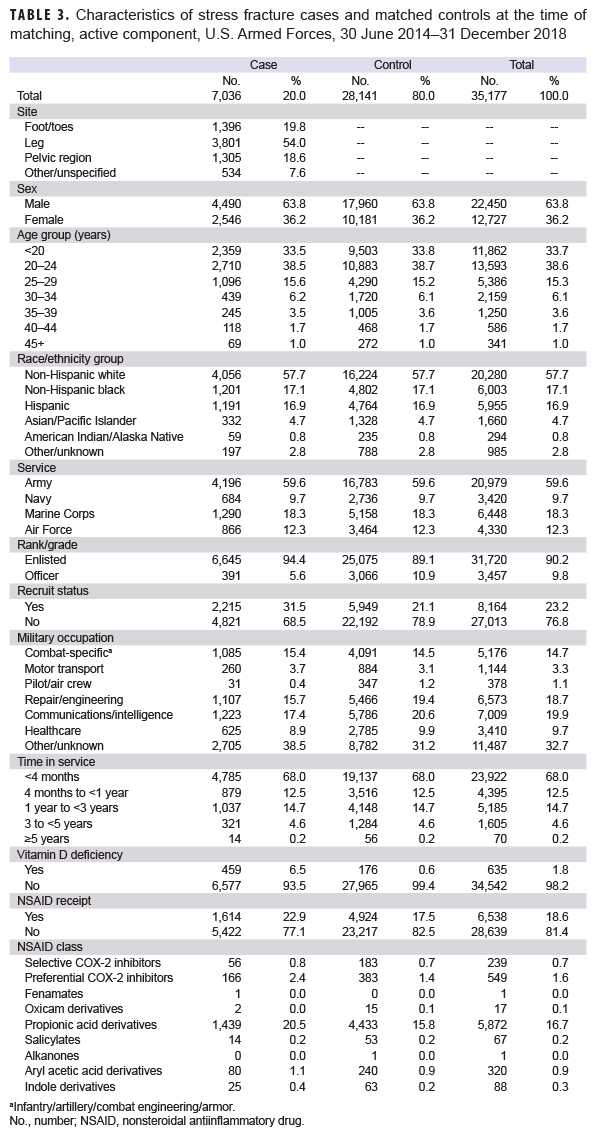

A total of 7,039 incident stress fracture cases were identified among active component service members from June 2014 through Dec. 2018; however, 3 cases were excluded from the analysis because matched controls could not be identified. The cases excluded were an Asian female Marine and two additional females who were older than 45 years old. A total of 28,141 controls were selected, resulting in a total sample size of 35,177 (Table 3). Among the cases, stress fractures occurred predominantly within the leg (54.0%). As a result of the matching process, the distribution of sex, race/ethnicity, age, service, and time in service was similar between cases and controls. Compared to controls, cases consisted of higher percentages of recruits (21.1% vs. 31.5%, respectively), enlisted personnel (89.1% vs. 94.4%, respectively), individuals with diagnosed vitamin D deficiency (0.6% vs. 6.5%, respectively), and NSAID receipt (17.5% vs. 22.9%, respectively). Propionic acid derivatives were the most common NSAIDs dispensed within the 30 to 180 days before the stress fracture diagnosis (for cases) or reference date (for controls) in the study population (16.7%), followed by preferential COX-2 inhibitors (1.6%) (Table 3). Of the propionic acid derivatives, the most commonly dispensed drugs were ibuprofen (56.4%) and naproxen (27%) (data not shown). In the final adjusted model, service members who received NSAIDs had an incidence of stress fracture diagnoses that was 1.70 times (95% CI: 1.58–1.82; p<.0001) that of those who had not received NSAIDs (data not shown). When this model was restricted to the Army population, soldiers who received NSAIDs had 1.64 times (95% CI: 1.49–1.80; p<0.0001) the incidence of stress fracture diagnosis compared to nonrecipients (data not shown).

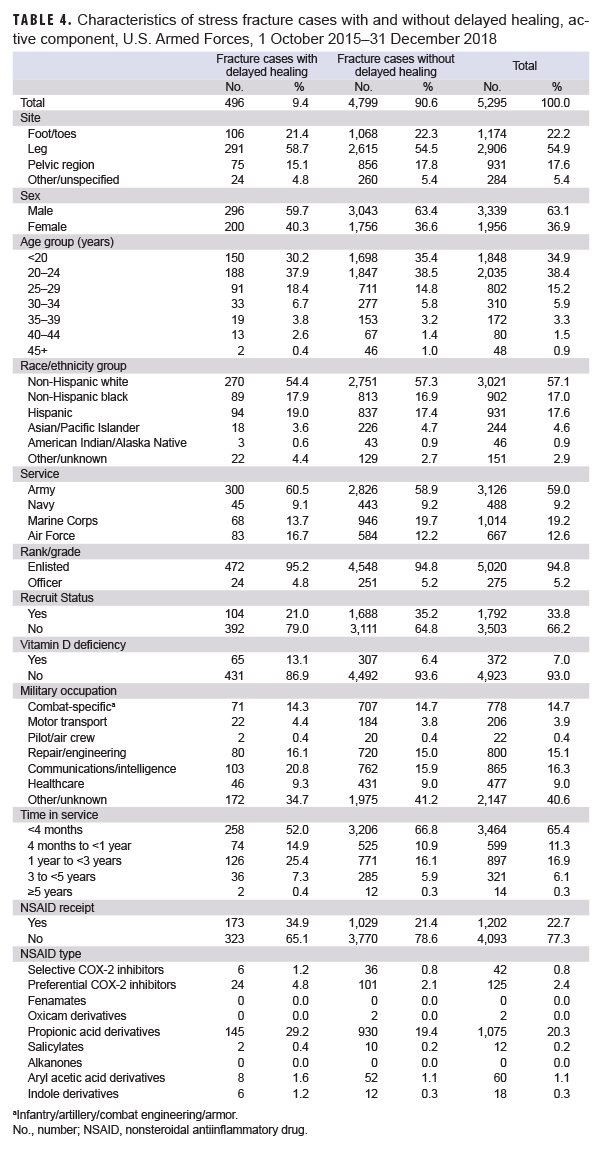

Of the 7,036 incident stress fracture cases identified in the first part of the study, 5,295 were diagnosed on or after 1 Oct. 2015, after the transition to the ICD-10 coding system, and were included in the second part of the analysis (Table 4). A total of 496 (9.4%) of these cases had a diagnosis for delayed healing within 90 days after the incident stress fracture diagnosis. Distribution of demographic and selected military characteristics among cases with and without delayed healing diagnoses were broadly similar, with the exception that a smaller percentage of delayed healing cases were among recruits (21.0% vs. 32.5%, respectively) and there was a greater percentage of diagnosed vitamin D deficiency among those with delayed healing diagnoses compared to those without (13.1% vs. 6.4%, respectively). In addition, a greater percentage of delayed healing fracture cases occurred among service members in the Air Force (16.7% vs 12.2%, respectively), among service members in communications/intelligence occupations (20.8% vs. 15.9%, respectively), and among service members with 1–3 years of time in service (25.4% vs 16.1%, respectively) compared to controls. In the final adjusted model, those stress fracture cases who received any NSAIDs had odds of a delayed healing diagnosis that were 1.41 times (95% CI: 1.12–1.77; p=.004) those of cases who did not receive any NSAIDs (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

This study found that active component service members who had previously received any NSAIDs experienced a 70% increased incidence in stress fracture diagnoses compared to those who had not received any NSAIDs. Studies of the risk of stress fracture after NSAID use have produced contradictory results. However, several studies suggest that NSAIDs increase risk of stress fractures, especially during times of intense physical training. One study conducted among U.S. Army personnel found that risk of stress fractures was significantly higher in NSAID users, and that this risk increased among the recruits in basic combat training,2 suggesting that NSAIDs do increase the risk for fractures, especially during times of intense physical training.

In a previous retrospective cohort study of regular and incidental NSAID users and control patients, the relative rate for nonvertebral fractures was higher among regular NSAID users in comparison to the control patients.6,7 However, there was no difference in rates of nonvertebral fractures between the regular and incidental users, which suggests that use of NSAIDs, not the duration of use, increases the risk for fractures.6,7

As a secondary objective, the current study examined whether dispensed NSAIDs were associated with diagnoses of delayed healing and found that stress fracture cases with previous NSAID receipt experienced 1.41 times the odds of a delayed healing diagnosis compared to nonrecipients. Previous animal and human studies have provided inconclusive evidence on the effect of NSAIDs on fracture healing.7,9,10,13–25 Results of several studies suggest the effect of NSAIDs on healing may be different depending on the type of fractures and the timing of NSAID use.7,10,11,15–17,22 Previous in vitro studies have found that NSAIDs inhibit the proliferation potential of osteogenic cells, deterring the differentiation of osteoblasts, which then prevents the formation of new bone.9,30–35 This finding lends support to the hypothesis that NSAID use may delay bone healing since the inhibition of these osteogenic cells would result in reduced bone resorption and formation.

The current study was designed to replicate a case-control study by Hughes and colleagues that examined NSAID use and risk of stress fracture among Army members.2 However, there were some key differences in the designs of this study and the current study. The current study used the same NSAID exposure definition; however, more classes of NSAIDs were included in the current analysis because literature has suggested that these drugs have an effect on osteoblast and osteoclast proliferation.9,10,15,16,32–34 The current study used a case definition similar to that used by Hughes and colleagues with the exception that pathological fractures were excluded to avoid any misclassification of fractures from illness.10 The current study also randomly sampled controls by a 4:1 ratio, with risk-set matching on several demographic variables, while the Hughes and colleagues' study only matched on time in service. The stricter matching rules and shorter study period employed in the current study identified a smaller number of cases than in the reference study. Both studies had a potential for reverse causation because service members could have had prior NSAID use to treat the pain of a pre-clinical stress fracture. In an effort to minimize potential reverse causation, the current study did not consider NSAID use within 30 days before the reference date as exposure to NSAIDs. The reference study used the same rule after conducting a lagged analysis comparing 15-, 30-, and 45-day gaps between NSAID use and stress fracture-related encounter.2 Based on their analysis, the reference study used a 30-day gap in the exposure definition.2 The reference study found that NSAID receipt was associated with a 2.9 times increase in stress fracture risk for the Army population, while the current study found a 1.64 times increase in incidence of stress fracture when restricted to Army service members only (data not shown).2 Although both studies demonstrated a statistically significant positive association between prior NSAID receipt and incident stress fracture, the reference study found a more pronounced association.

There are several limitations to the current study. Service members were included as exposed if they had received prescribed NSAIDs; however, medication adherence could not be measured. In addition, severity of stress fracture cannot be determined from administrative health care records. Furthermore, individuals may be misclassified as nonexposed if they took over-the-counter NSAIDs. In particular, it is likely the study did not capture instances of ibuprofen or aspirin self-medication for service members who used only over-the-counter drugs, which would not be reflected in Military Health System prescription records. Service members were considered exposed if they received NSAIDs 30 to 180 days before the reference date; however, for recruits, prescription data before basic training were not available, so this data gap may also have resulted in exposure misclassification.

Prospective studies are recommended to confirm the associations between prior receipt of NSAIDs and increased incidence of stress fractures and delayed bone healing and to reduce the possibilities of misclassification bias and reverse causation. If confirmed, these findings may have significant implications for military readiness because NSAIDs are used extensively and stress fractures are already a major contributor to the burden of health care encounters and lost duty time.36,37 Treatment recommendations for stress fractures may need to be adapted to focus more heavily on preventive measures and ensuring adequate healing time with reduced emphasis on NSAID use for relieving pain and swelling symptoms.

References

- Jones BH, Hauschild VD, Canham-Chervak M. Musculoskeletal training injury prevention in the U.S. Army: evolution of the science and the public health approach. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21(11):1139–1146.

- Hughes JM, McKinnon CJ, Taylor KM, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug prescriptions are associated with increased stress fracture diagnosis in the US Army population. J Bone Miner Res. 2019;34(3):429–436.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Stress fractures, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2004–2010. MSMR. 2011;18(5):8–11.

- Wood AM, Hales R, Keenan A, et al. Incidence and time to return to training for stress fractures during military basic training. J Sports Med. 2014;2014:282980.

- Walker L, Zambraski E, Williams RF. Widespread use of prescriptions nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs among U.S. Army active duty soldiers. Mil Med. 2017;182(3):e1709–e1712.

- van Staa TP, Leufkens HG, Cooper C. Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and risk of fractures. Bone. 2000;27(4):563–568.

- Wheeler P, Batt ME. Do non-steroidal antiinflammatory drugs adversely affect stress fracture healing? A short review. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(2):65–69.

- Stovitz SD, Arendt EA. NSAIDs should not be used in treatment of stress fractures. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70(8):1452–1454.

- Pountos I, Georgouli T, Calori GM, Giannoudis PV. Do nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs affect bone healing? A critical analysis. ScientificWorldJournal. 2012;2012:606404.

- Hughes JM, Popp KL, Yanovich R, Bouxsein ML, Matheny RW Jr. The role of adaptive bone formation in the etiology of stress fracture. Exp Biol Med (Maywood). 2017;242(9):897–906.

- Blackwell KA, Raisz LG, Pilbeam CC. Prostaglandins in bone: bad cop, good cop? Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2010;21(5):294–301.

- Kaji H, Sugimoto T, Kanatani M, Fukase M, Kumegawa M, Chihara K. Prostaglandin E2 stimulates osteoclast-like cell formation and boneresorbing activity via osteoblasts: role of cAMPdependent protein kinase. J Bone Miner Res. 1996;11(1):62–71.

- Lisowska B, Kosson D, Domaracka K. Positives and negatives of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs in bone healing; the effects of these drugs on bone repair. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2018;12;1809–1814.

- Gerstenfeld LC, Thiede M, Seibert K, et al. Differential inhibition of fracture healing by nonselective and cyclooxygenase-2 selective nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Orthop Res. 2003;21(4):670–675.

- Chow JW, Chambers TJ. Indomethacin has distinct early and late actions on bone formation induced by mechanical stimulation. Am J Physiol. 1994;267(2 pt 1):e287–e292.

- Jankowski CM, Shea K, Barry DW, et al. Timing of ibuprofen use and musculoskeletal adaptations to exercise training in older adults. Bone Rep. 2015;1:1–8.

- Kohrt WM, Barry DW, Van Pelt RE, Jankowski CM, Wolfe P, Schwartz RS. Timing of ibuprofen use and bone mineral density adaptations to exercise training. J Bone Miner Res. 2010;25(6):1415–1422.

- Daluiski A, Ramsey KE, Shi Y, et al. Cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitors in human skeletal fracture healing. Orthopedics. 2006;29(3);259–261.

- Herbenick MA, Sprott D, Stills H, Lawless M. Effects of a cyclooxygenase 2 inhibitor on fracture healing in a rat model. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2008;37(7):e133–e137.

- Murnaghan M, Li G, Marsh DR. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug-induced fracture nonunion: an inhibition of angiogenesis? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(suppl 3):140–147.

- Nagano A, Arioka M, Takahasi-Yanaga F, Matsuzaki E, Sasaguri T. Celecoxib inhibits osteoblast maturation by suppressing the expression of Wnt target genes. J Pharmacol Sci. 2017;133(1):18–24.

- Altman RD, Latta LL, Keer R, Renfree K, Hornicek FJ, Banovac K. Effect of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs on fracture healing: a laboratory study in rats. J Orthop Trauma. 1995;9(5):392–400.

- Butcher CK, Marsh DR. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs delay tibial fracture union. Injury. 1996;27(5):375.

- Giannoudis PV, MacDonald DA, Matthews SJ, Smith RM, Furlong AJ, De Boer P. Nonunion of the femoral diaphysis. The influence of reaming and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82(5):655–658.

- Adolphson P, Abbaszadegan H, Jonsson U, Dalén N, Sjöberg HE, Kalén S. No effects of piroxicam on osteopenia and recovery after Colles’ fracture. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, prospective trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1993;112(3):127–130.

- Furuya T, Hosoi T, Tanaka E, et al. Prevalence of and factors associated with vitamin D deficiency in 4,793 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2013;32(7):1081–1087.

- Nadolski, CE. Vitamin D and chronic pain: promising correlates. US Pharm. 2012;37(7):42–44.

- Sonneville KR. Gordon CM, Kocker MS, Pierce LM, Ramappa A, Field AE. Vitamin D, calcium, and dairy intakes and stress fractures among female adolescents. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012;166(7):595–600.

- Miller JR, Dunn KW, Ciliberti LJ Jr, Patel RD, Swanson BA. Association of vitamin D with stress fractures: a retrospective cohort study. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2016;55(1):117–120.

- Wang Y, Chen X, Zhu W, Zhang H, Hu S, Cong X. Growth inhibition of mesenchymal stem cells by aspirin: involvement of the wnt/ß-catenin signal pathway. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2006;33(8):696–701.

- Chang JK, Wang GJ, Tsai ST, Ho ML. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug effects on osteoblastic cell cycle, cytotoxicity, and cell death. Connect Tissue Res. 2005;46(4–5):200–210.

- Chang JK, Li CJ, Lia HJ, Wang CK, Wang GJ, Ho ML. Anti-inflammatory drugs suppress proliferation and induce apoptosis through altering expressions of cell cycle regulators and pro-apoptotic factors in cultured human osteoblasts. Toxicology. 2009;258(2–3):148–156.

- Ho ML, Chang JK, Chuang LY, Hsu HK, Wang GJ. Effects of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and prostaglandins on osteoblastic functions. Biochem Pharmacol. 1999;56(6):983–990.

- Evans CE, Butcher C. The influence on human osteoblasts in vitro of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs which act on different cyclooxygenase enzymes. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):444–449.

- Díaz-Rodríguez L, García-Martínez O, Morales MA, Rodríguez-Pérez L, Rubio-Ruiz B, Ruiz C Effects of indomethacin, nimesulide, and diclofenac on human MG-63 osteosarcoma cell line. Biol Res Nurs. 2012;14(1):98–107.

- Stahlman S, Taubman, SB. Incidence of acute injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2008–2017. MSMR. 2018;25(7):2–9.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 2019;26(5):2–10.