What Are the New Findings?

This is the first report to describe self reported data on smoking and vaping habits from the ePHA. Unadjusted incidence rates of acute respiratory infection (ARI) were highest among members who reported either e-cigarette/vaping product use, or smoking and e-cigarette/vaping product (dual-use) as compared to smokers and non-users. Adjusted incidence rates of ARI revealed that members who are dual-users had statistically significantly higher rates of ARI.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

This is the first report to describe self reported data on smoking and vaping habits from the ePHA. Unadjusted incidence rates of acute respiratory infection (ARI) were highest among members who reported either e-cigarette/vaping product use, or smoking and e-cigarette/vaping product (dual-use) as compared to smokers and non-users. Adjusted incidence rates of ARI revealed that members who are dual-users had statistically significantly higher rates of ARI.

Abstract

Smoking is known to contribute to the risk of acute respiratory illness (ARI) and long-term medical conditions but little is known about the acute health effects of e-cigarette/vaping product use. The annual electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA), which includes questions related to smoking and e-cigarette/vaping product use, is a screening tool used by the U.S. Armed Forces to evaluate the health and medical readiness of military members. Based on responses to questions on ePHAs completed in 2018, active component service members (ACSMs) were categorized as e-cigarette/vaping product only users, smoking only, dual-product users (users of both cigarettes and e-cigarette/vaping products), or non-users. ACSMs in the youngest age groups were more likely than their older counterparts to use e-cigarette/vaping products. Unadjusted incidence rates of ARI were higher among e-cigarette/vaping product only users and dual-product users than smokers and nonusers. After adjusting for age, sex, service branch, and military occupation, the incidence rate of ARI among dual-product users was higher than the rate among nonusers; this difference was small but statistically significant. Improved understanding of the health impact of e-cigarette/vaping product use has the potential to inform policy related to use of these products and prevent unnecessary harm.

Background

An estimated 200,000–300,000 active component service members (ACSM) are diagnosed with acute respiratory infection (ARI) annually.1-6 ARI among ACSMs affects their ability to perform their duties because of lost duty hours for medical visits and sick days required for recovery.

Numerous studies have linked smoking to cardiovascular disease, lung disease, and premature death.7 Smoking also contributes to the risk of infectious diseases, including ARI, in both smokers and those exposed to secondhand smoke.8-11 There has been a rapid increase in the use of electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes), vaping products, and other electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) among adolescents and young adults in the U.S. According to the 2018 National Health Interview Survey, among young adults aged 18–24 years, prevalence of reported current e-cigarette use was 7.6% (up from 5.2% in 2017).12 The popularity of these products raises the concern that e-cigarette/vaping product use, may, like smoking, contribute to the burden of respiratory infections and illnesses.13-16

The Department of Defense’s annual electronic Periodic Health Assessment (ePHA), which includes questions related to smoking and tobacco product use, is a screening tool used by the Armed Forces to evaluate the health and medical readiness of military members. In 2018, questions about smoking and e-cigarette/vaping product use were added to the ePHA questionnaire allowing respondents to provide detailed information about their smoking and other tobacco use behaviors. Among the 1.2 million ACSM ePHA respondents since 2018, over 113,000 reported using cigarettes, 63,000 reported using e-cigarette/vaping products, and 6,700 reported using both cigarettes and e-cigarette/vaping products (AFHSD, unpublished data, 2019).

The aims of this study were twofold. The first aim was to describe the demographic and military characteristics of self-reported smokers, e-cigarette/vaping product users, users of both smoking and e-cigarette/vaping products (dual-product users), and nonusers among ACSMs. The second aim was to compare incidence rates of ARI among groups of self-reported cigarette smokers, e-cigarette/vaping product users, dual-product users, and nonusers. To date, there have been no studies that examine the relationship between self-reported use of e-cigarette/vaping products and ARI among ACSMs.

Methods

Data used in this study were derived from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) which includes inpatient and outpatient medical encounter data, Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS) data, and ePHA results. The surveillance period was 01 Jan. 2018 through 30 Sept. 2019. The surveillance population included all ACSMs in the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps who completed an ePHA questionnaire between 1 Jan. 2018 and 31 Dec. 2018. ACSMs whose DMSS records contained diagnoses of underlying chronic respiratory diseases including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, emphysema, chronic bronchitis, or bronchiectasis at any time were excluded.17-19 If an ACSM completed more than 1 ePHA during the study period, only the most recent ePHA data were included.

ACSMs were classified into 4 different exposure categories based on self-reported past 30-day (recent) tobacco product use. Exposure category was determined by an ACSM’s response to the following ePHA question: "In the past 30 days, which of the following products have you used on at least one day?" Respondents were classified as smoking only if they did not endorse "electronic cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or vape pens" but responded affirmatively to using any of the following: "cigarettes", "cigars, cigarillos, or little cigars", "hookahs or water-pipes", "pipes filled with tobacco (not water-pipes)", or "bidis (small brown cigarettes wrapped in a leaf)". Respondents were categorized as e-cigarette/vaping product only users if they endorsed the response option "electronic cigarettes, e-cigarettes, or vape pens" and did not endorse any of the smoking products. Dual product users included those who were classified as both smokers and e-cigarette/vaping product users. Respondents were identified as nonusers if they marked "none" or only endorsed any of the following: "chewing tobacco, snuff, or dip", "snus" (moist tobacco powder placed under the lip), "dissolvable tobacco products", or "other" (specify). The nonuser group also included all ever users who had not used any products in the past 30 days.

Demographic and military characteristics of ACSMs as well as duration of tobacco use and exposure to secondhand smoke were examined by user group. Demographic and military characteristics obtained from the DMSS included age, sex, race/ethnicity group, education level, service branch, rank/grade, military occupation, and marital status. Background characteristics from the ePHA included number of deployments in the past five years, previous tobacco use, with duration of any tobacco product use categorized as "less than 1 year", "1 to 5 years", "5 to 10 years", “11 to 15 years", or "more than 15 years", and exposure to secondhand smoke, determined by using responses to the yes/no question "Are you regularly exposed to secondhand smoke, a mixture of smoke that comes out of the burning end of a cigarette, cigar, pipe and the smoke breathed out by the smoker (housemate, carpool, work environment)?"

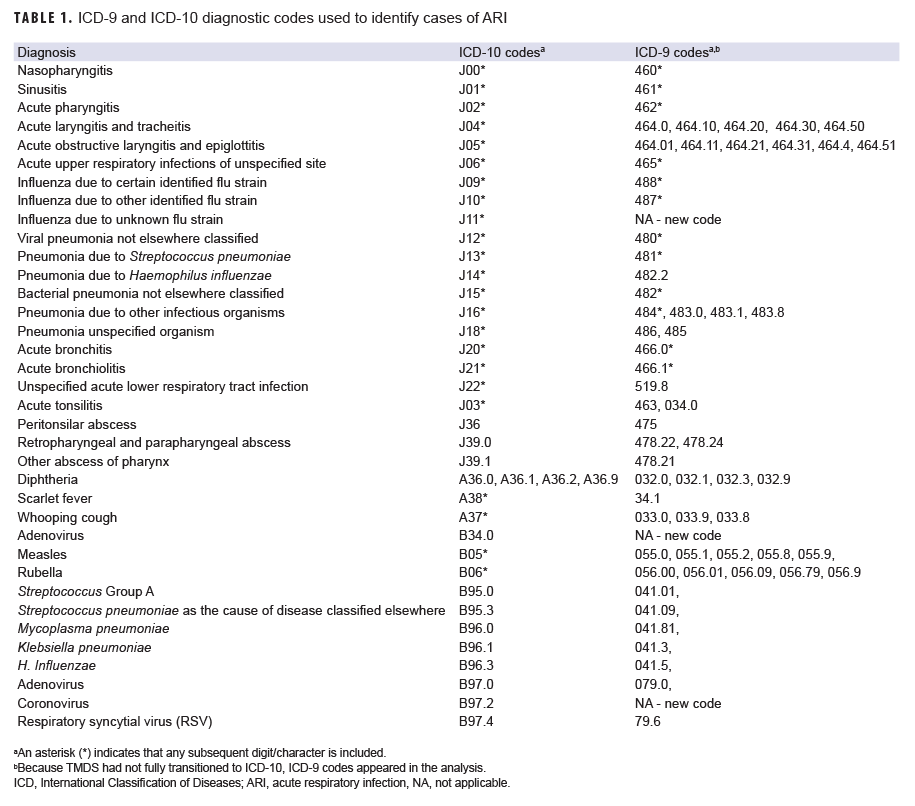

Incident cases of ARI among the ACSMs in the 4 groups were identified during the 9 months following ePHA administration date using a retrospective cohort study design. The case definition was 1 inpatient, outpatient or TMDS encounter with a qualifying diagnosis of ARI occurring in the first diagnostic position (Table 1). Incident cases were identified using a 14-day gap rule; ICD-9 and ICD10 codes for ARI were not counted in the 14 days after the first recorded code, as they likely represented a continuation of the same ARI and not a new incident case of ARI. It is important to note that, because TMDS had not fully transitioned to ICD-10, ICD-9 codes appeared in the analysis. Multivariable Poisson regression models were used to calculate adjusted incidence rate ratios (AIRRs) for the user groups using nonusers as the referent and controlling for age, sex, service branch, and military occupation. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

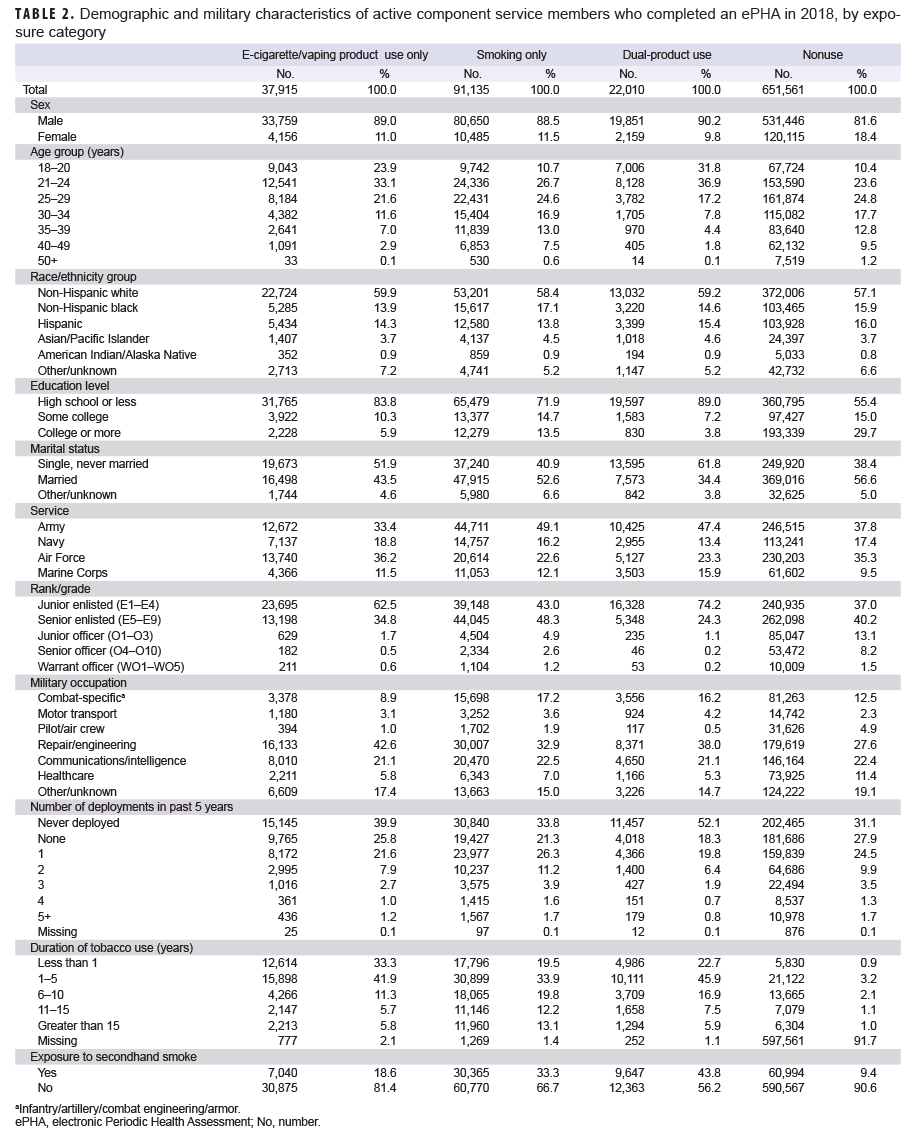

Of the 802,621 ACSMs who completed an ePHA in 2018, 651,561 (81.2%) were nonusers, 37,915 (4.7%) were e-cigarette/vaping product only users, 91,135 (11.4%) were in the smoking only group, and 22,010 (2.7%) were dual-product users (Table 2). Nearly one-quarter (23.9%) of e-cigarette/vaping product only users and 31.8% of dual-product users were under 21 years old, as compared to 10.7% of smokers, and 10.4% of nonusers. More than half (56.9%) of e-cigarette/vaping product only users were under 25 years old and more than two-thirds (68.8%) of dual-product users were under 25 years old. The distributions of race/ethnicity group and service branch were broadly similar across the user groups.

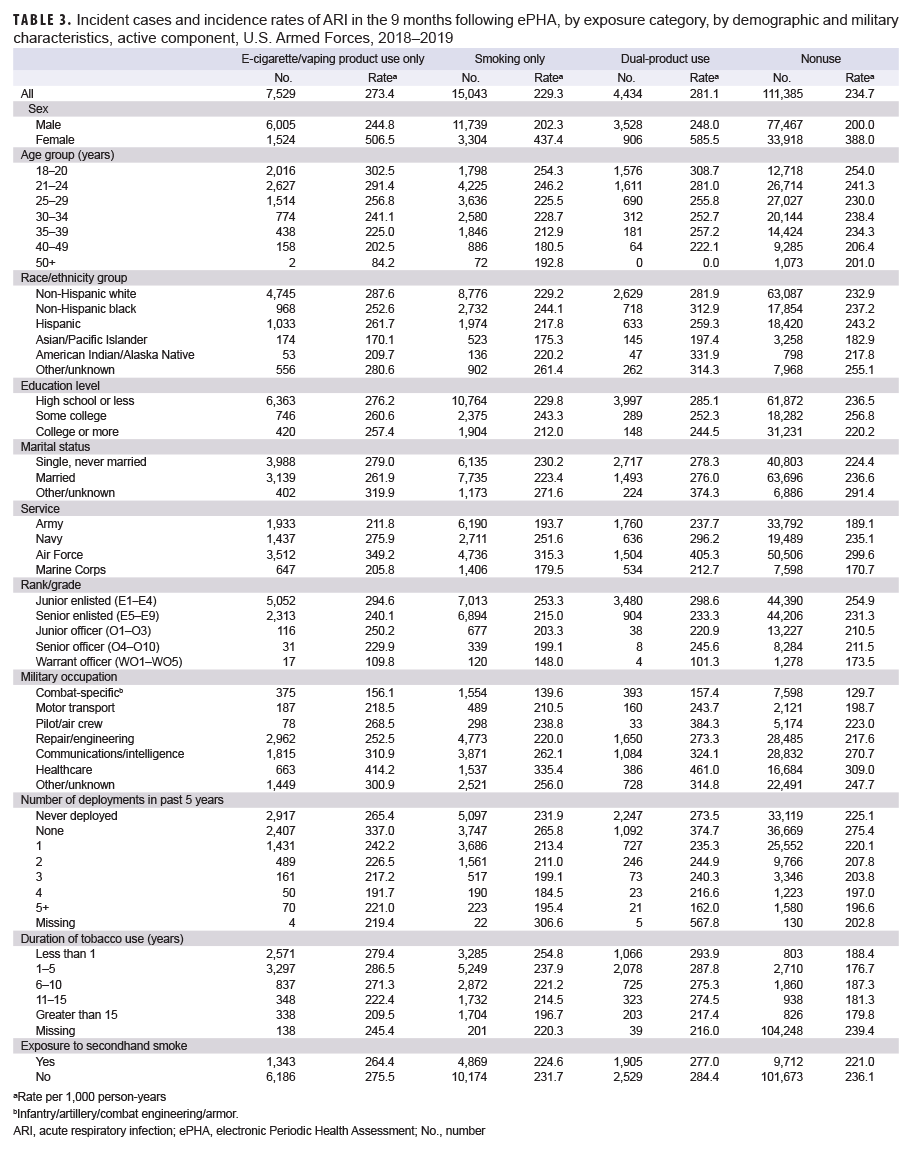

Among ACSMs who completed an ePHA in 2018, the crude incidence rates of ARI per 1,000 person-years (p-yrs) during the 9 months after assessment were 281.1 for dual-users, 273.4 for e-cigarette/vaping product only users, 234.7 for non-users, and 229.3 for smokers (Table 3). Across all groups, the incidence rates of ARI among females were at least 1.9 times those of males (IRR for female nonusers was 1.9 times that of males, IRR for female dual-users was 2.4 times that of males). In all study groups, incidence rates of ARI were highest among ACSMs 18–20 years old and generally decreased with increasing age. Incidence rates of ARI were highest among e-cigarette/vaping product only users and dual-product users with an education level of high school or less compared to those with higher levels of educational attainment. Similarly, the incidence rates of ARI were highest among e-cigarette/vaping product only users and dual-product users in ranks E1–E4 and decreased with increasing rank. The incidence rates of ARI were highest among ACSMs who had not deployed in the past 5 years (Table 3).

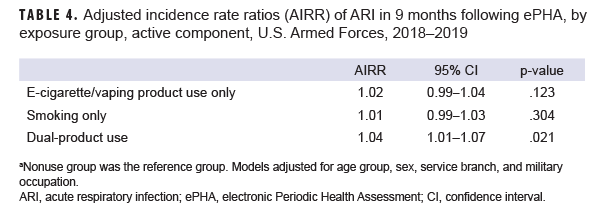

After adjusting for age, sex, service branch, and military occupation, e-cigarette/vaping product only users and those in the smoking only group had similar incidence rates of ARI compared to nonusers (AIRR=1.02, 95% CI: 0.99–1.04, p=.123; AIRR=1.01, 95% CI: 0.99–1.03, p=.304, respectively) (Table 4). The rate of ARI among dual-product users was higher than the rate among nonusers; this difference was small but statistically significant (AIRR=1.04, 95% CI: 1.01-1.07, p=.021).

Editorial Content

The majority of ACSMs who reported e-cigarette/vaping product only use were less than 25 years old. A majority of e-cigarette/vaping product only users and dual product users had a high school education or less, a rank of E1–E4, never deployed, and were single, never married. More than half of those in the e-cigarette/vaping product only or dual-product user categories reported using any tobacco products for 5 years or less. This is consistent with reports that adolescents in middle and high school initiate use of e-cigarettes/vaping products.13,20

Female service members made up similar percentages of smokers, e-cigarette/vaping product users and dual users. Published data on sex differences in e-cigarette/vaping product use are limited. Some studies suggest that males are more likely to use e-cigarettes/vaping products than females, but rapidly evolving marketing techniques and social messaging have the potential to change these patterns.21

The youngest age group had the highest incidence rates of ARI across all user groups and the nonuser group. Incidence rates of ARI tended to decrease with increasing age. Women had incidence rates of ARI that were twice the rates of men across all the user groups. Women have been reported to demonstrate increased care seeking behavior compared to men, which may partially explain this finding.22

ACSMs who reported dual use of e-cigarette/vaping products and smoking products on the ePHA during 2018 had the highest crude incidence rate of ARI, followed by e-cigarette/vaping product only users. After adjusting for age, sex, service branch, and military occupation, ACSMs who self-reported dual-product use had a statistically significantly higher rate of ARI compared to compared to nonusers, although the difference was small.

This study has several limitations. First, self-report of health-risk behaviors can be associated with under-reporting. Second, other factors that mitigate or aggravate the risk of ARI (including living environment [e.g., barracks vs an apartment/house], contact with young children, stress, and other comorbidities) were not considered here. Third, recruits completing basic or early training are not included in this study population, as the first ePHA is completed after training at the first permanent duty station. Fourth, the current analysis did not adjust for race/ethnicity group or education level which have been shown to be associated with tobacco use behavior. Fifth, the difference in the adjusted rates of ARI among dual-product users and nonusers, although statistically significant, was very small. Further analysis may provide evidence as to whether this difference is relevant. Finally, while the ePHA is mandatory, completion rates differ by the different service branches such that the study population does not fully represent the actual ACSM population.

Current findings suggest that dual use of e-cigarette/vaping and smoking products may be associated with ARI. However, further investigation of this potential relationship should take into account the type of e-cigarette/vaping product used as well as the duration and frequency of use. The ePHA provides a rich source of data related to e-cigarette/vaping product use that can be merged with other data sources to monitor health impacts over time. Studies adjusting for factors not considered here, such as race/ethnicity group and education are warranted. Gaining a better understanding of the risks associated with e-cigarette use/vaping is important for ensuring both the short- and long-term health of ACSMs. Such an understanding would promote military readiness, especially given that e-cigarette/vaping product users tend to be younger with potentially long military careers ahead of them.

Author Affiliations: Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (CDR Clausen, Dr. Stahlman, Dr. Ziadeh); Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (LCDR Sanou).

Acknowledgements: The authors would like to thank Ms. Zheng Hu, data analyst, at the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division.

Disclaimer: The contents, views or opinions expressed in this publication or presentation are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense (DoD), or Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force. Mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government.

References

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2018. MSMR. 26(5):2–10.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2017. MSMR. 25(5):2–9.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2015. MSMR. 23(4):2–6.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013. MSMR. 21(4):2–7.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2012. MSMR. 20(4):5–10.

- Sanchez JL, Cooper MJ, Myers CA, et al. Respiratory infections in the U.S. military: Recent experience and control. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):743–800.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking and Tobacco Use. Health Effects. https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/basic_information/health_effects/. Accessed 15 Jan. 2020.

- Vanker A, Gie RP, Zar HG. The association between environmental tobacco smoke exposure and childhood respiratory disease: a review. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2017;11(8):661–673.

- Feldman C, Anderson, R. Cigarette smoking and mechanisms of susceptibility to infections of the respiratory tract and other organ systems. J Infect. 2013; 67(3):169–184.

-

Hsieh SJ, Zhuo H, Bennowitz NL et al. Prevalence and impact of active and passive cigarette smoking in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Crit Care Med. 2014;42(9):2058–2068.

- Arcavi L, Benowitz NL. Cigarette smoking and infection. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2206–2216

- Dai H, Leventhal AM. Prevalence of e-cigarette use among adults in the United States, 2014–2018. JAMA. 2019; 322(18):1824–1827.

- Soneji S, Barrington-Trimis JL, Wills TA, et al. Association between initial use of e-cigarettes and subsequent cigarette smoking among adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and metaanalysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(8):788–797.

- Gilpin DF, McGown KA, Gallagher K, et al. Electronic cigarette vapour increases virulence and inflammatory potential of respiratory pathogens. Respir Res. 2019;20(1):267.

- Yu V, Rahimy M, Korrapati A, et al. Electronic cigarettes induce DNA strand breaks and cell death independently of nicotine in cell lines. Oral Oncol. 2016 (2):58–65.

- Wu Q, Jiang D, Minor M. et al. Electronic cigarette liquid increases inflammation and virus infection in primary human airway epithelial cells PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108342.

- Hewitt, R, Farne H, Ritchie A, et al The role of viral infections in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(2)158–174.

- Kim V and Criner GJ. Chronic bronchitis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;187(3):228–237.

- Juhn YJ. Risks for infection in patients with asthma (or other atopic conditions): is asthma more than a chronic airway disease? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(2):247–257.

- Gentzke AS, Creamer M. Vital signs: Tobacco product use among middle and high school students – United States 2011–2018. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 68(6);157–164.

- Kong, G, Kuguru, KE, Krishnan-Sarin S. Gender differences in U.S. adolescent e-cigarette use Curr Addict Rep. 2017;4(4):422–430.

- Bertakis KD, Azari R, Helms LJ, Callahan EJ, and Robbins JA. Gender differences in the utilization of health care services. J Fam Pract. 2000;249(2):147.