What Are the Findings?

The 2019-2020 influenza vaccine provided moderate protection against influenza for beneficiary and civilian populations within the Department of Defense (DOD) and low to moderate protection against influenza for active component service members.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Components of the influenza vaccine can change each season and novel influenza strains can appear and circulate among active component and DOD beneficiary populations. Conducting Vaccine Effectiveness (VE) studies every year can assist vaccine policy makers in making their decisions on strain selection for the influenza vaccine for the subsequent season, thus creating the most effective influenza vaccine, which can reduce morbidity and improve military readiness.

Abstract

This report provides mid-season VE estimates from the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD), the DOD Global Respiratory Pathogen Surveillance (DODGRS) program, and the Naval Health Research Center (NHRC) for the 2019-2020 influenza season. Using a test negative case-control study design, the AFHSD performed a VE analysis for active component service members while the DODGRS program and NHRC collaborated to perform a VE analysis for DOD beneficiaries and U.S.-Mexico border civilians. Among active component service members, there was low to moderate protection against influenza B, moderate protection against A(H3N2), and non-statistically significant low protection against influenza A overall and A(H1N1). Among DOD beneficiaries and U.S.-Mexico border civilians, there was statistically significant moderate protection against influenza B, influenza A overall, A(H1N1), and A(H3N2).

Background

Historically, military populations have been stationed in congregate settings that predispose them to acute respiratory infections, resulting in significantly increased morbidity, which has impacted military readiness.1 In previous seasons, it was estimated that 300,000 to 400,000 active component service members had medical encounters for respiratory infections.2 Specifically, influenza has had a significant impact on the military population for over a century. During the influenza pandemic of 1918, 43,000 U.S. service members were killed due to the H1N1 pandemic strain that was circulating at the time, constituting approximately 40% of all U.S. war deaths during World War I.3 On a yearly basis, the U.S. military requires influenza vaccination among active component personnel, with a goal of exceeding 90% immunization by mid-Dec. of each year.2

Despite the high vaccination rate among the military population, vaccine breakthrough cases still occur. From 2007 through 2012, the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD) reported 7,000–25,000 cases of influenza infections to the Military Health System each week of the influenza seasons, 3,000 to 16,000 of which were military personnel.2,4,5 The Department of Defense conducts year-round influenza surveillance for military health beneficiaries and civilian populations, and the DOD uses these data to estimate midseason influenza VE, which is submitted annually to the Food and Drug Administration Vaccine and Related Biological Advisory Committee meeting. This report presents the mid-season VE estimates from the DOD 2019–2020 influenza season surveillance.

Methods

Two separate analyses were performed to produce mid-season DOD VE estimates, both using a test-negative, case-control study design. The study population for the AFHSD analysis consisted of active component service members from the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps stationed in the U.S. and abroad who were tested for influenza. Subjects were identified using the Defense Medical Surveillance System Health Level 7 data from the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center, and service member data from the Naval Health Research Center (NHRC) for specimens collected for influenza testing from 1 Nov. 2019 to 15 Feb. 2020. The AFHSD identified cases by either a positive reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), viral culture, or rapid test. Cases were laboratory-confirmed influenza positives and controls were influenza test negatives. Active component service members with a negative rapid test were excluded. Influenza vaccination status was ascertained through documentation in medical records. Subjects were considered vaccinated if the laboratory specimens were collected 14 days or more after vaccination. Crude and adjusted VE estimates were calculated using odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) obtained from multivariable logistic regression models. VE estimates were adjusted for sex, age category, and month of specimen collection. VE was calculated as (1−OR) × 100. Results were stratified by influenza subtype. Due to differences in the timing of circulating influenza strains this season, the influenza B and influenza A(H3N2) analyses used specimens from the entire period of 1 Nov. 2019 to 15 Feb. 2020, whereas the influenza A overall and influenza A(H1N1) analyses were restricted to the peak influenza A circulation period of 1 Jan. 2020 to 15 Feb. 2020. Influenza A(H3N2) cases were few and sporadic throughout the season, which is why the entire period was used. All vaccinated populations were restricted to subjects who received inactivated influenza vaccine because the live attenuated influenza vaccine was not routinely used among active component service members during the 2019–2020 season.

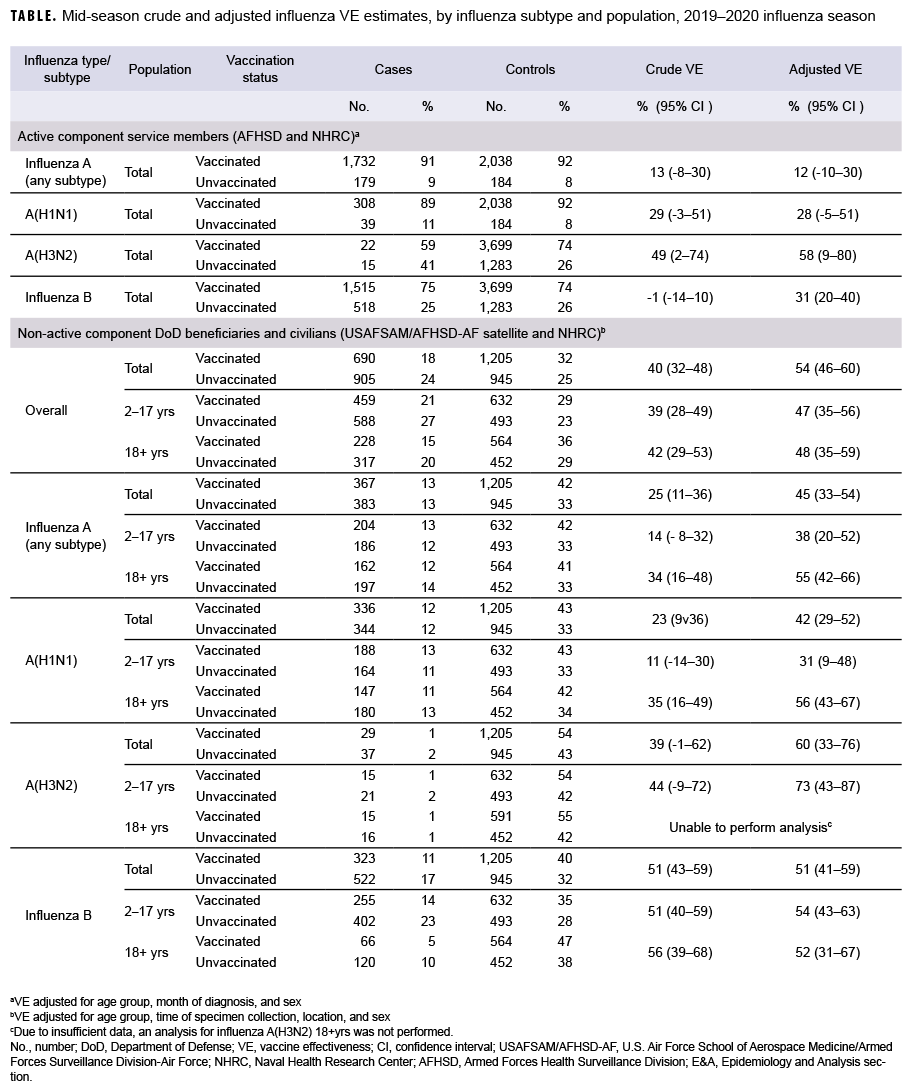

The DOD Global Respiratory Pathogen Surveillance (DODGRS) program and NHRC combined their surveillance data to estimate VE among DOD beneficiaries and civilians whose specimens were collected from 3 Nov. 2019 to 15 Feb. 2020. Active component members were excluded from this analysis. Data from the DODGRS program pertained to DOD dependents who visited military treatment facilities and whose specimens were sent to and tested at the U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine (USAFSAM). NHRC's data pertained to civilian populations who visited clinics near the U.S.-Mexico border and outpatient DOD beneficiaries in Southern California and Illinois. Cases were patients whose laboratory tests confirmed the presence of influenza virus, and controls were patients whose influenza tests were negative. Cases and controls were identified by RT-PCR and/or viral culture. Vaccination status was determined through electronic immunization records from the Air Force Complete Immunization Tracking Application or self-report from questionnaires. Individuals were considered vaccinated if they received the vaccine at least 14 days prior to their specimen collection date. Those whose vaccination status could not be ascertained or those who were vaccinated within 14 days prior to their illness were excluded. Crude and adjusted VE estimates for this analysis were also calculated using ORs and 95% CIs obtained from multivariable logistic regression models. VE estimates were adjusted for age group, time of specimen collection, location, and sex. VE was calculated as (1−OR) × 100. Results were stratified by influenza subtype and population (all dependents, aged 2-17 years, and aged 18 years or older) (Table 1). Because of insufficient data, a sub-analysis for the elderly population (aged 65 years or older) was not possible.

Results

For AFHSD's active component service member influenza B and A(H3N2) analysis (Nov. to Feb.), there were 2,033 and 37 laboratory-confirmed cases of influenza B and A(H3N2), respectively, and 4,982 test-negative controls. For AFHSD's active component service member influenza A (any subtype) and A(H1N1) analysis (Jan. to Feb.), there were 1,911 and 347 laboratory-confirmed cases of influenza A (any subtype) and A(H1N1), respectively, and 2,222 test-negative controls. Although the crude VE estimate for influenza B was not statistically significantly different from zero, the adjusted VE estimate was statistically significant at 31%. The crude and adjusted VE estimates for influenza A(H3N2) were statistically significant at 49% and 58%, respectively. The adjusted VE estimates for influenza A (any subtype) and A(H1N1) did not reach statistical significance at 12% and 28%, respectively. The confidence intervals for crude and adjusted VE estimates are shown in the Table.

For the USAFSAM/NHRC DOD beneficiary and civilian analysis, there were 1,595 confirmed cases and 2,150 controls. With the exception of influenza A(H3N2) in adults, all adjusted VE estimates were statistically significantly different from zero. Moreover, the VE estimates were substantially higher for influenza B (unadjusted and adjusted) and influenza A(H3N2) (adjusted) than for influenza A(H1N1) and all influenza A subtypes.

Editorial Comment

Among active component service members, the mid-season 2019–2020 estimates of influenza vaccine effectiveness indicated moderate protection against A(H3N2) (58%), low to moderate protection against influenza B (31%), and non-statistically significant low protection against influenza A overall (12%) and A(H1N1) (28%). Estimates for the DOD beneficiaries and civilian population indicate a statistically significant moderate protection against overall influenza diagnosis (54%), influenza B (51%), influenza A (any subtype) (45%), A(H1N1) (42%), and A(H3N2) (60%). Mid-season VE estimates for active component service members were higher and statistically significant compared with the previous season.7 This could potentially be due to the 2019–2020 season being more severe and having a higher volume of testing, which resulted in a larger sample size and improved statistical power of the analyses. VE estimates for the DOD beneficiaries and civilian populations were similar to interim estimates from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's VE analysis for the 2019–2020 influenza season.8

There were limitations to these analyses. Results for the active component service member analysis are for medically attended illnesses that were tested for influenza; therefore, the result may not be applicable to less severe illnesses that did not result in a medical encounter for the 2019– 2020 influenza season. Among the active component service member population, influenza vaccination is mandatory, so this population is highly immunized. This could have a negative impact on VE, with potential statistical issues and biological effects such as attenuated immune response with repeated exposures. The DOD beneficiaries and civilians analysis was unable to calculate VE estimates for the elderly population due to insufficient data. Additionally, self-reported data from the questionnaire could result in potential recall bias on the analysis. However, this bias was curtailed for self-reported vaccination status by excluding those whose status could not be ascertained and electronic immunization records were used instead, if available.

Because of the rapidly changing nature of the influenza virus, it is imperative for researchers to continue to assess the effectiveness of the influenza vaccine, as well as to enhance methods of VE analyses for more accurate estimates, and to take waning immunity and repeated vaccinations into account. Future research on these concepts could bring forth benefits and have an influence on decision-making for vaccination policies, especially for the military.

Author affiliations: STS Systems Integration, LLC, San Antonio, TX (Mr. Thervil, Ms. DeMarcus); Wright-Patterson Air Force Base-Air Force satellite, U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, Ohio (Mr. Thervil, Ms. DeMarcus); Cherokee Nation Strategic Solutions, Tulsa, OK (Dr. Cost, Ms. Hu); Defense Health Agency, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Cost, Ms. Hu); Naval Health Research Center, San Diego, CA (Dr. Myers, Dr. Hollis, Ms. Balansay-Ames, Ms. Ellis, Dr. Christy); General Dynamics Information Technology, San Diego, CA (Ms. Balansay-Ames, Ms. Ellis).

Disclaimer: The authors are military service members or employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C. §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C. §101 defines a U.S. Government work as work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties. Report No. 21-21 was supported by Global Emerging Infections Surveillance & Response System Operations (GEIS) under work unit nos. 60501 and GEIS Promis ID P0151_20_US_01. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, Department of Defense, nor the U.S. Government.

References

- Ho ZJM, Hwang YFJ, Lee JMV. Emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases: challenges and opportunities for militaries. Mil Med Res. 2014;1:21.

- Sanchez JL, Cooper MJ, Myers CA, et al. Respiratory infections in the U.S. military: recent experience and control. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2015;28(3):743-800.

- Clarke T Jr. Pandemic, 1918. Mil Med. 2016; 81(8):941-942.

- Sanchez JL, Cooper MJ. Influenza in the US military: an overview. J Infect Dis Treat. 2016;2:1.

- Update: pneumonia-influenza and severe acute respiratory illnesses, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, July 2000-June 2012. MSMR. 2012;19:11-13.

- Toure E, Eick-Cost AA, Hawksworth AW, et al. Brief report: mid-season influenza vaccine effectiveness estimates for the 2016-2017 influenza season. MSMR. 2017;24(8):17-19.

- Lynch LC, Coleman R, DeMarcus L, et al. Brief report: Department of Defense midseason estimates of vaccine effectiveness for the 2018-2019 influenza season. MSMR. 2019;26(7):24–27.

- Dawood FS, Chung JR, Kim SS, et al. Interim estimates of 2019–20 seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness—United States, Feb. 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:177-182.