Background

Chronic infection with hepatitis C virus (HCV) can cause significant morbidity to individuals due to inflammatory damage to the liver. This chronic inflammatory damage can lead to further complications, including cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, and fulminant liver failure. In the military, HCV presents a concern for fitness for duty, readiness, and health care costs of its members.

In the U.S., prevalence of chronic HCV infection is approximately 1%.1 From 2010–2019, estimated annual acute HCV incidence increased 387%2; increased detection was driven at least in part by improved and expanded testing recommendations as well as increased injection drug use within the opioid abuse epidemic.3,4 During this timeframe, the majority of new HCV infections occurred in those aged 20–39 (which approximates the ages of those joining the military).2

In 2020, the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD),5 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF),6 and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)7 expanded recommendations for HCV infection screening to include all adults age 18 years or older (and for all pregnant women during each pregnancy) because of cost effectiveness, limited success of risk-based screening, and availability of curative treatment.

Active HCV infection disqualifies an individual from military accession because its proper clinical management conflicts with initial training and mission readiness. Three disqualifying criteria for active or recent HCV infection include: history of chronic HCV without successful treatment or without documentation of cure 12 months after completion of a full course of therapy; acute infection within the preceding 6 months; or persistence of symptoms or evidence of impaired liver function. Force screening for HCV is not currently performed during U.S. Air Force (USAF) Basic Military Training (BMT) although screening is completed for other viral infections (including HIV, hepatitis A, and hepatitis B). As a result, the true prevalence of chronic HCV infection cannot be ascertained in the basic trainee population. However, the prevalence can be estimated based on the number of HCV infections confirmed following positive screening during trainee blood donations.

Trainees voluntarily donate blood near the end of BMT and are thus able to donate only once while at BMT. Concurrent testing for HCV antibody and HCV RNA occurs at the time of blood donation. If a trainee's blood tests positive for HCV antibody but negative for HCV RNA, a third generation enzyme immunoassay (EIA) is used for confirmation. A positive test for HCV antibody in addition to either a positive HCV RNA or EIA test indicates active infection. Alternatively, a positive HCV antibody test in an individual with negative RNA and EIA tests typically denotes a cleared infection.

From Nov. 2013 through April 2016, the estimated prevalence of HCV infection among volunteer recruit blood donors at Joint Base San Antonio (JBSA)-Lackland Blood Donor Center was 0.007%.8 The goal of this inquiry was to estimate the most recent prevalence of HCV infections within the USAF basic training population during 2017–2020.

Methods

The JBSA-Lackland Blood Donor Center was queried for the results of HCV screening for all basic military trainees who donated blood between Jan. 1, 2017 and Dec. 31, 2020. All other blood donations (those from individuals other than basic trainees) during this time period were excluded. HCV prevalence in those who donated blood was calculated using the total trainee donations as the denominator. Since trainees are only able to donate once before departing BMT, these donations represent unique trainees. The numerator included those who screened positive upon donation and were also confirmed to have active infection upon subsequent testing. Positive HCV cases were ascertained from a local database, which included demographic, diagnostic, and laboratory data for all USAF recruits, maintained by Trainee Health Surveillance. This database was queried for International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnostic codes K70–K77 (diseases of the liver) and B15–B19 (viral hepatitis); the codes for all hepatitides were initially utilized so as to conduct a wide search in case of coding errors. A possible case was defined as a trainee receiving a qualifying ICD-10 code in any diagnostic position during an outpatient medical encounter and was restricted to 1 case per person during the surveillance period. The electronic medical records of possible cases were reviewed and those diagnosed with current HCV infection due to blood screening from BMT blood donation were counted as true cases. Such screened positive BMT cases were confirmed by comparing them to those reported by the Blood Donation Center. The Fisher's exact test for count data was used to compare the prevalence computed for the period from 2017 through 2020 to the prevalence during the period from 2013 through 2016.

Results

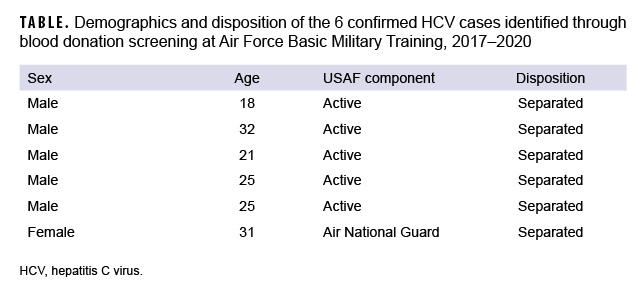

From 2017 through 2020, 29,615 unique individual trainees from USAF BMT donated blood (out of 146,325 total trainees attending BMT during that time) and had their blood donations screened for HCV. From this group, a total of 85 individuals screened positive for HCV antibodies; of these, 6 were confirmed to be positive for active HCV infection (positive HCV RNA or EIA) (Table). The prevalence of HCV in those BMT trainees who were screened from 2017 through 2020 was 0.0203% (6 of 29,615 screened) (data not shown), which is 3.1 times (p=.173) the prevalence of HCV infection in this population during 2013–2016 (0.0065%, 2 of 30,660 screened).8 Of note, during 2017–2020, one additional case of HCV in BMT was diagnosed clinically based on symptoms; however, this case was excluded in the prevalence calculation because it was not from a blood donation.

Editorial Comment

The prevalence of HCV infection in BMT trainee blood donors from 2017 through 2020 was 3.1 times the prevalence among trainees who donated from 2013 through 2016.8 While the difference in prevalence was not statistically significant (p=.173), it may reflect the recent increases in incidence among U.S. young adults, as noted by the CDC,2 perhaps due to increased injection drug use.3,4

This study is limited in that the screened blood came from only those trainees attempting to donate blood, so the data do not directly estimate HCV prevalence for all trainees as would be the case from a random sample of the entire BMT trainee population. If the prevalence in blood donors reflected that in basic trainees overall, there would have been approximately 30 active HCV infections among basic trainees during the 4 year period; and of these, only approximately 20% were detected through blood donor screening.

Instituting accession-wide HCV screening at USAF BMT by adding it to the current lab evaluation would be an efficient method of ensuring that all new USAF enlisted service members are up to date on this screening as recommended by USPSTF, CDC, and AASLD.

Author affiliations: 559th Trainee Health Squadron, JBSA-Lackland, TX (Maj Kasper, Capt Holland, and Maj Kieffer); Office of the Command Surgeon, Air Education and Training, JBSA-Randolph, TX (Maj Frankel); 59th Medical Wing, Science and Technology, JBSA-Lackland, TX (Ms. Cockerell); Air Force Medical Readiness Agency, Falls Church, VA (Lt Col Molchan).

Disclaimer: The views expressed are those of the authors and do not reflect the official views or policy of the Department of Defense or its Components. In addition, the opinions expressed on this document are solely those of the authors and do not represent endorsement by or the views of the United States Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

References

- Hofmeister MG, Rosenthal EM, Barker LK, et al. Estimating prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 2013–2016. Hepatology. 2019;69(3):1020–1031.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2019 Viral Hepatitis Surveillance Report- Hepatitis C. Published July 2021. Accessed 9 Aug. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/hepatitis/statistics/2019surveillance/HepC.htm

- Zibbell JE, Asher AK, Patel RC, et al. Increases in acute hepatitis C virus infection related to a growing opioid epidemic and associated injection drug use, United States, 2004 to 2014. Am J Public Health. 2018;108(2):175–181.

- Suryaprasad AG, White JZ, Xu F, et al. Emerging epidemic of hepatitis C virus infections among young nonurban persons who inject drugs in the United States, 2006-2012. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;59(10):1411–1419.

- Ghany MG, Morgan TR; AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2019 Update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases – Infectious Diseases Society of America recommendations for testing, managing, and treating hepatitis C virus infection. Hepatology. 2020;71(2):686–721.

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Owens DK, Davidson KW, et al. Screening for hepatitis C virus infection in adolescents and adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2020;323(10):970–975.

- Schillie S, Wester C, Osborne M, Wesolowski L, Ryerson AB. CDC Recommendations for hepatitis C screening among adults - United States, 2020. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2020;69(2):1–17.

- Taylor DF, Cho RS, Okulicz JF, Webber BJ, Gancayco JG. Brief report: Prevalence of hepatitis B and C virus infections in U.S. Air Force basic military trainees who donated blood, 2013-2016. MSMR. 2017;24(12):20–22.