What are the new findings?

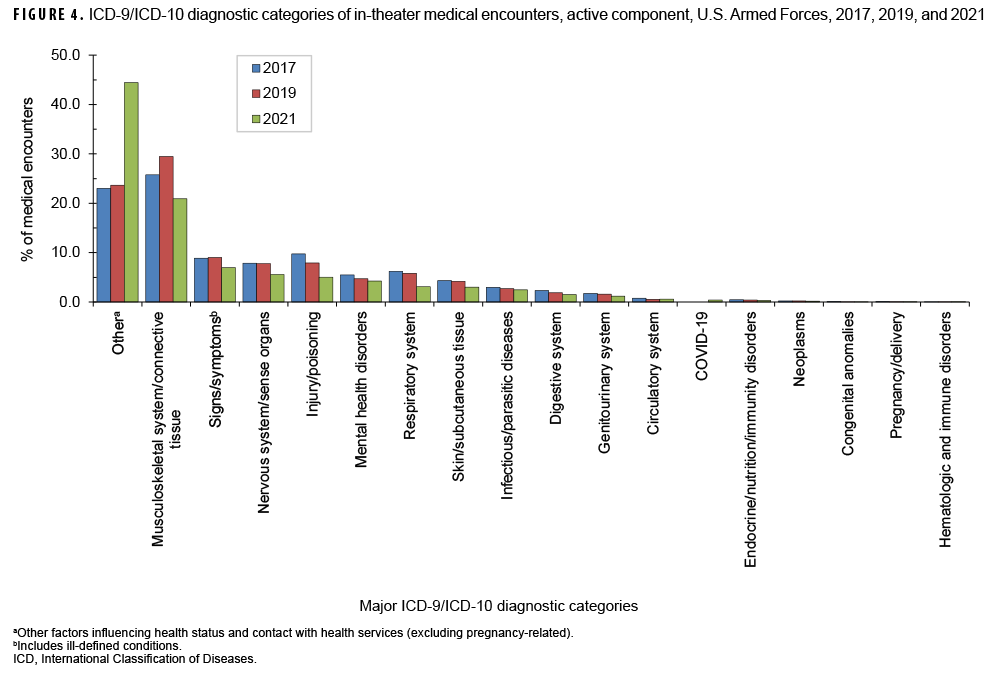

As in previous years, among service members deployed during 2021, injury/poisoning, musculoskeletal diseases and signs/symptoms accounted for more than half of the total health care burden during deployment. Compared to garrison disease burden, deployed service members had relatively higher proportions of encounters for respiratory infections, skin diseases, and infectious and parasitic diseases. The recent marked increase in the percentage of total medical encounters attributable to the ICD diagnostic category "other" (23.0% in 2017 to 44.4% in 2021) is likely due to increases in diagnostic testing and immunization associated with the response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Injuries and musculoskeletal diseases account for the greatest burden of deployed medical care and continued focus on surveillance and preventive measures for these health threats is warranted. While deployed, readiness may be impacted by conditions associated with austere environmental and sanitary conditions.

Every year, the MSMR estimates illness-and injury-related morbidity and health care burdens on the U.S. Armed Forces and the Military Health System (MHS) using electronic records of medical encounters from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). These records document health care delivered in the fixed medical facilities of the MHS and in civilian medical facilities when care is paid for by the MHS. Health care encounters of deployed service members are documented in records that are maintained in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS), which is incorporated into the DMSS. This report updates previous analyses examining the distributions of illnesses and injuries that accounted for medical encounters (“morbidity burdens”) of active component members in deployed settings in the U.S. Central Command (USCENTCOM) and the U.S. Africa Command (USAFRICOM) areas of operations during the 2021 calendar year.1

Methods

The surveillance population included all individuals who served in the active or reserve components of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps and who had records of health care encounters captured in the TMDS during the surveillance period. The analysis was restricted to encounters where the theater of care specified was USCENTCOM or USAFRICOM or where the name of the theater of operation was missing or null; by default, this excluded encounters in the U.S. Northern Command, U.S. European Command, U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, or U.S. Southern Command theaters of operations. In addition, TMDS-recorded medical encounters where the data source was identified as Shipboard Automated Medical System (e.g., SAMS, SAMS8, SAMS9) or where the military treatment facility descriptor indicated that care was provided aboard a ship (e.g., USS George H.W. Bush or USS Dwight D. Eisenhower) were excluded from this analysis. Encounters from aeromedical staging facilities outside of USCENTCOM or USAFRICOM (e.g., the 779th Medical Group Aeromedical Staging Facility or the 86th Contingency Aeromedical Staging Facility) were also excluded. Inpatient and outpatient medical encounters were summarized according to the primary (first-listed) diagnoses (if reported with an International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10] code between A00 and U09 or beginning with Z37). Primary diagnoses that did not correspond to an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code (e.g., 1XXXX, 4XXXX) were not reported in this burden analysis.

In tandem with the methodology described on pages 2–3 of this issue of the MSMR, all illness- and injury-specific diagnoses were grouped into 153 burden of disease-related conditions and 25 major categories based on a modified version of the classification system developed for the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study.2 The morbidity burdens attributable to various conditions were estimated on the basis of the total number of medical encounters attributable to each condition (i.e., total hospitalizations and ambulatory visits for the condition with a limit of 1 encounter per individual per condition per day) and the numbers of service members affected by the conditions. In general, the GBD system groups diagnoses with common pathophysiologic or etiologic bases and/or significant international health policymaking importance. For this analysis, some diagnoses that are grouped into single categories in the GBD system (e.g., mental health disorders) were disaggregated. Also, injuries were categorized by the affected anatomic sites rather than by causes because external causes of injuries are not completely reported in TMDS records. It is important to note that because the TMDS has not fully transitioned to ICD-10 codes, some ICD-9 codes appear in this analysis. In addition to the examination of the distribution of diagnoses by the 153 conditions and the 25 major categories of disease burden, a third analysis depicts the distribution of diagnoses according to the 17 traditional categories of the ICD system, plus an 18th category dedicated to COVID-19.

Results

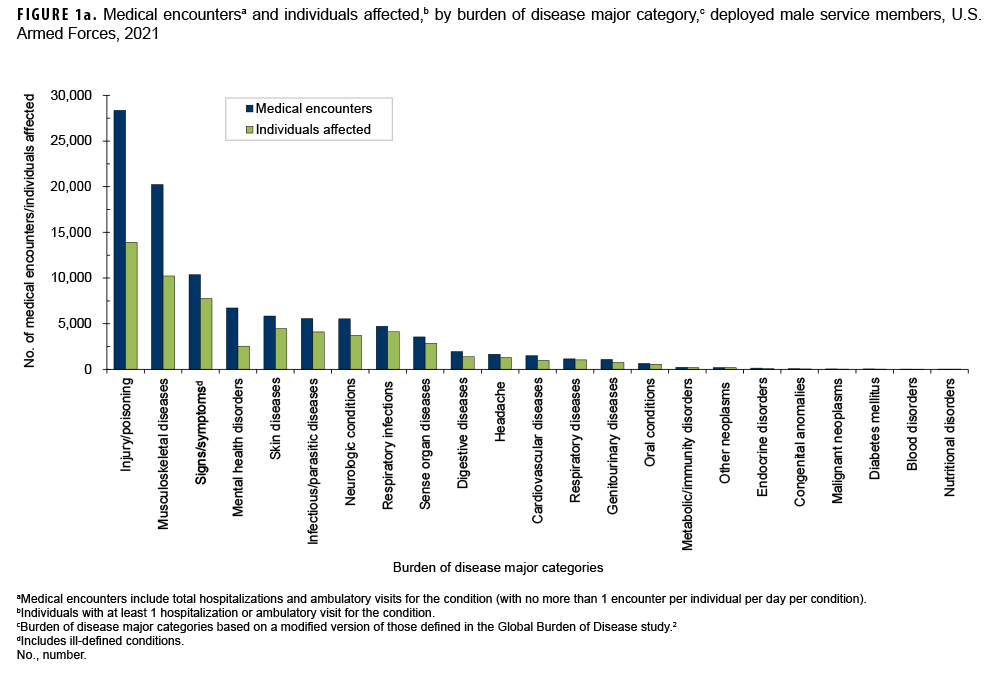

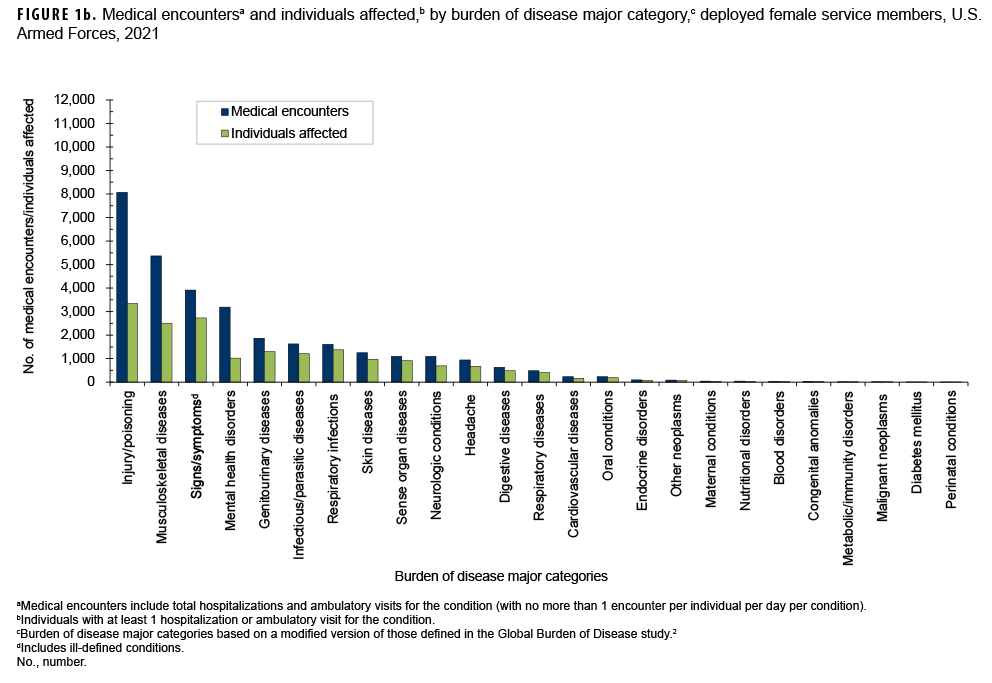

In 2021, a total of 131,694 medical encounters occurred among 48,457 individuals while deployed to Southwest Asia/Middle East and Africa. Of the total medical encounters, 141 (0.11%) were indicated to be hospitalizations (data not shown). A majority of the medical encounters (75.7%), individuals affected (79.9%), and hospitalizations (79.4%) occurred among male service members (Figures 1a, 1b).

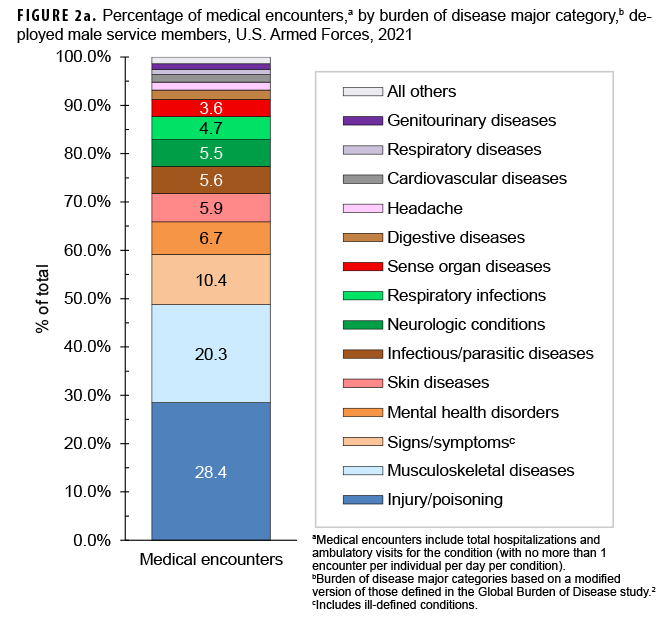

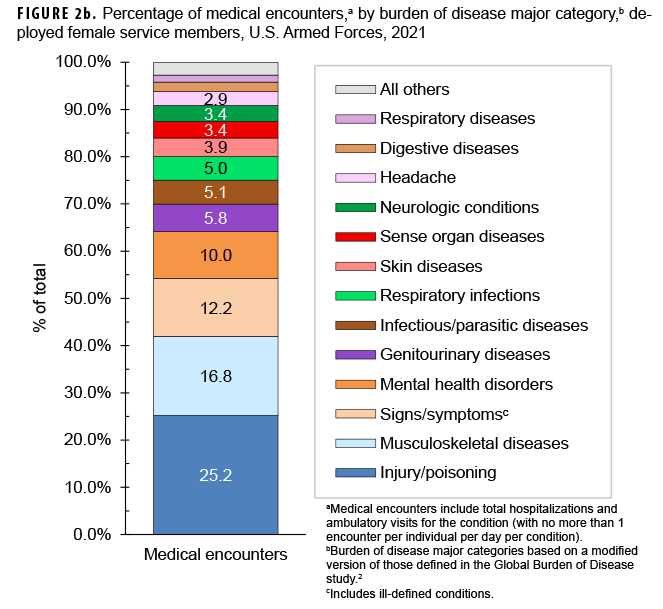

Medical encounters/individuals affected by burden of disease categories

During 2021, the percentages of total medical encounters by burden of disease categories in both deployed male and female service members were generally similar; in both sexes, more encounters were attributable to injury/poisoning, musculoskeletal diseases, and signs/symptoms (including ill-defined conditions) than any other categories (Figures 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b). The substantial burden of these disease categories on total medical encounters was also reflected as the top-3 categories for which individuals received medical care while deployed. Of note, female service members had a greater proportion of medical encounters for genitourinary diseases (5.8%) compared to male service members (1.1%).

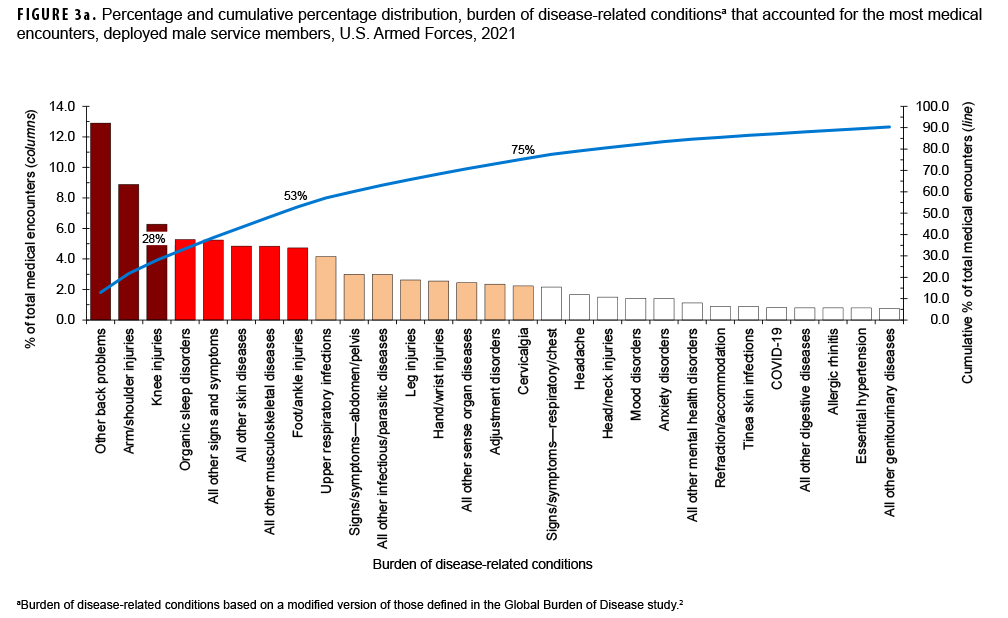

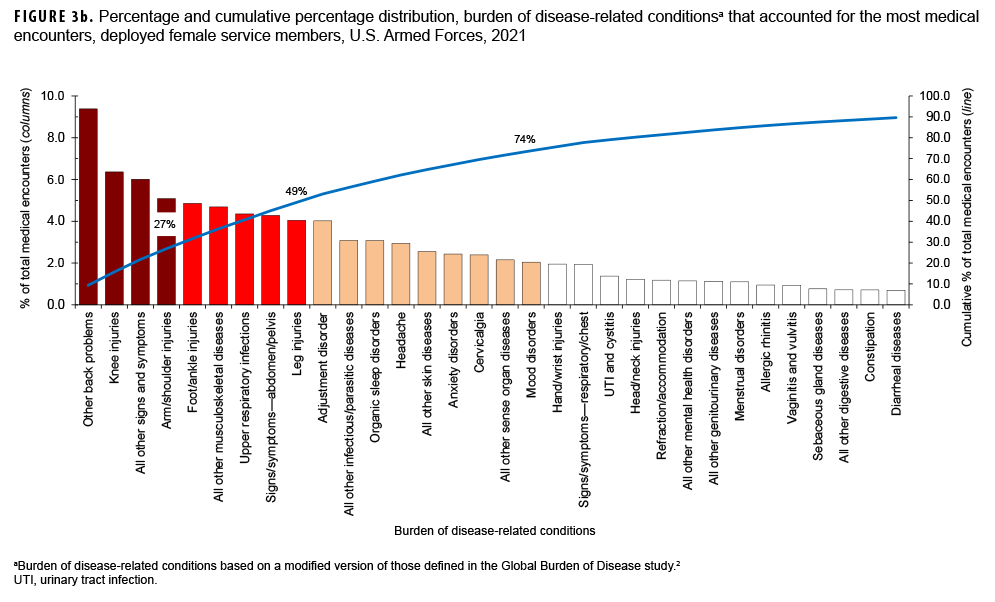

Among both male and female service members, 4 burden conditions (other back problems, arm/shoulder injuries, knee injuries, and all other signs and symptoms) were among the top 5 burden conditions that accounted for the most medical encounters in 2021 (Figures 3a, 3b). The remaining burden conditions among the top 5 were organic sleep disorders (specifically, circadian rhythm disorders) among male service members and foot and ankle injuries among female service members.

The 4-digit ICD-10 code with the most medical encounters in the other back problems category during 2021 was for low back pain (data not shown). For all other musculoskeletal diseases, the most common 4-digit ICD code for both male and female service members was for cervicalgia. The most common 4-digit ICD-10 codes for arm/shoulder injuries and knee injuries were for pain in the specified body part (e.g., pain in right or left shoulder or pain in right or left knee) (data not shown). The 4-digit ICD-10 code with the third most medical encounters was for acute upper respiratory infection, unspecified (data not shown).

Of note, among male service members, less than 0.3% of all medical encounters during deployment were associated with any of the following major morbidity categories: metabolic/immunity disorders, other neoplasms, endocrine disorders, congenital anomalies, malignant neoplasms, diabetes mellitus, blood disorders, and nutritional disorders (Figure 1a). Among female service members, less than 0.3% of all medical encounters during deployment were associated with maternal conditions, nutritional disorders, blood disorders, congenital anomalies, metabolic/immunity disorders, malignant neoplasms, diabetes mellitus, and perinatal conditions (Figure 1b).

Medical encounters by major ICD-10 diagnostic category

In 2021, among the 18 major ICD-10 diagnostic categories, the largest percentages of medical encounters were attributable to “other” (includes factors influencing health status and contact with health services as well as external causes of morbidity), followed by musculoskeletal system/connective tissue (Figure 4). The percentage of total medical encounters attributable to “other” increased from 23% in 2017 to 44% in 2021. The top 3 most common ICD-10 diagnoses in the “other” category in 2021 included Z11.59 (28%, Encounter for screening for other viral diseases), Z02.89 (19%, Encounter for other administrative examinations), and Z23 (16%, Inoculations and vaccinations). Encounters for COVID-19 accounted for 0.4% of the total medical encounters in 2021 (data not shown). The percentage of medical encounters attributable to injury and poisoning decreased from 9.8% in 2017 to 5.0% in 2021 (Figure 4). The percentages of medical encounters attributable to the remaining major ICD diagnostic categories were relatively similar during the years 2017, 2019, and 2021.

Editorial Comment

This report documents the morbidity and health care burden among U.S. military members while deployed to Southwest Asia/Middle East and Africa during 2021. Similar to results from earlier surveillance periods,1,3,4 3 burden categories—injury/poisoning, musculoskeletal diseases, and signs/symptoms—together accounted for more than one-half of the total health care burden in theater among both male and female deployers. The 2021 percentages of encounters due to “other” health encounters may have been driven by increased screening and vaccination for COVID-19, although this was not investigated in detail in this report.

Compared to the distribution of major burden of disease categories documented in garrison, this report also demonstrates relatively greater proportions of in-theater medical encounters due to respiratory infections, skin diseases, and infectious and parasitic diseases. The lack of certain amenities and greater exposure to austere environmental conditions may have compromised hygienic practices and contributed to this finding. In contrast, compared to the distribution of burden of disease in garrison, a relatively lower proportion of in-theater medical encounters due to mental health disorders was observed.5 This finding may be due to a number of factors including pre-deployment screening and the continued emphasis on promoting psychological health and resilience in deployed service members.

However, 4 of the top 5 major burden of disease categories in-theater—injury/poisoning, musculoskeletal diseases, signs/symptoms, and mental health disorders—were the same as those reported in non-deployed settings.5 Injury/poisoning ranked first in both settings and musculoskeletal diseases ranked second in-theater and third in non-deployed settings.5 The similarity in these top conditions is likely attributable to the fact that both deployed and non-deployed populations generally comprise young and healthy individuals undergoing strenuous physical and mental tasks.

Encounters for certain conditions are not expected to occur often in deployment settings. For example, the presence of some conditions (e.g., diabetes, pregnancy, or congenital anomalies) makes the affected service members ineligible for deployment. As a result of this selection process, deployed service members are generally healthier than their non-deployed counterparts and, specifically, less likely to require medical care for conditions that preclude deployment. The overall result of such predeployment medical screening is diminished health care burdens (as documented in the TMDS) related to certain disease categories.

Interpretation of the data in this report should be done with consideration of some limitations. Not all medical encounters in theaters of operation are captured in the TMDS. Some care is rendered by medical personnel at small, remote, or austere forward locations where electronic documentation of diagnoses and treatment is not feasible. As a result, the data described in this report likely underestimate the total burden of health care actually provided in the areas of operation examined. In particular, some emergency medical care provided to stabilize combat-injured service members before evacuation may not be routinely captured in the TMDS. Another limitation derives from the potential for misclassification of diagnoses due to errors in the coding of diagnoses entered into the electronic health record. Although the aggregated distributions of illnesses and injuries found in this study are compatible with expectations derived from other examinations of morbidity in military populations (both deployed and non-deployed), instances of incorrect diagnostic codes (e.g., coding a spinal cord injury using a code that denotes the injury was suffered as a birth trauma rather than using a code indicating injury in an adult) warrant caution in the interpretation of some findings. Although such coding errors are not common, their presence serves as a reminder of the extent to which this study depends on the capture of accurate information in the sometimes austere deployment environment in which health care encounters occur.

References

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division. Morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, deployed active and reserve component service members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2020. MSMR. 2021; 28(6): 34–39.

- Murray CJ and Lopez AD, eds. In: Global Burden of Disease: A Comprehensive Assessment of Mortality and Disability from Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors in 1990 and Projected to 2020. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996:120–122.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries in deployed (per Theater Medical Data Store [TMDS]) active and reserve component service members, U.S. Armed Forces, 2008–2014. MSMR. 2015;22(8):17–22.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, deployed active and reserve component service members, 2019. MSMR. 2015;27(5):33–38.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Absolute and relative morbidity burdens attributable to various illnesses and injuries, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2021. MSMR. 2022;29(6):2–X.