Deployed service members regularly undergo demanding and stressful experiences that can contribute to mental health difficulties; however, there is a scarcity of studies examining rates of mental health disorders in-theater. The current study examined case rates of mental health disorders among deployed U.S. Army Soldiers using diagnostic encounter data from the Theater Medical Data Store. Case rates were calculated across 12 categories of mental health disorders. While in theater, soldiers’ highest rates were for stress reactions and adjustment disorders, depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders. The lowest rates in theater were for psychosis, bipolar, somatic, and eating disorders. Notably, female soldiers had higher rates than their male counterparts for disorders in each of the 12 diagnostic categories. Results provide crucial information to aid in decision making about necessary interventions and provider competencies in deployed settings. Knowledge gained from these data may improve force readiness, help lessen disease burden, and inform military policy and prevention efforts.

What are the new findings?

The disorders with the highest case rates in-theater included stress reactions/adjustment disorders, depression, anxiety, and sleep disorders, followed by PTSD and ADD/ADHD. Of particular note, in each of the 12 diagnostic categories examined, female soldiers had consistently higher rates than their male counterparts.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

These results emphasize the crucial need for in-theater behavioral health providers to be competent in the delivery of effective, short-term treatments for stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep disruptions. Further, these findings may contribute to the development of new policies and interventions to better prepare, support, and treat soldiers during deployments.

Mental health is a significant concern within the U.S. military, and service members are at substantial risk for developing an array of mental health conditions including anxiety, depression, stress/adjustment issues, and sleep-related disorders.1,2 Approximately 20% of the active duty population was diagnosed with at least 1 mental health disorder in 2016.3 Importantly, these mental health issues affect not only force health and readiness but also contribute to the morbidity, hospitalization, and overall attrition of military personnel.4-6

To date, most research examining rates of mental health diagnoses in the military has been conducted post-deployment (e.g., Hoge et al.7). Despite high rates of mental health disorders after deployment7,8 (e.g., 7% depression and 11% posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD] estimated from the Post-deployment Health Assessment8), few studies have examined the rates at which service members are diagnosed with a mental health disorder while deployed. Wojcik and colleagues evaluated in-theater diagnoses among soldiers deployed to an overseas contingency operating area between September 2001 and December 2004.9 The most frequent diagnoses were mood, adjustment, and substance-abuse disorders. White, female, enlisted soldiers were among those at highest risk for nearly all mental health disorders examined in the Wojcik study. However, these rates were assessed only as they related to psychiatric hospitalizations, thus providing insight only into the incidence of diagnoses severe enough to warrant inpatient care. Larson and colleagues also examined in-theater diagnoses and found the most frequently diagnosed disorders were, in descending order, anxiety (including acute stress disorder and PTSD), adjustment, and mood disorders.10 Their results were limited in that they examined diagnoses across 1 year (January 2006 to February 2007) in a single division (1st Marine Division) deployed to 1 province in Iraq (Al Anbar). However, both of these studies further support the evidence that rates of diagnosis of mental health disorders in the U.S. military population differ by sex4,11 and racial/ethnic background of the patient.4

Deployed service members regularly undergo demanding and stressful experiences that can contribute to mental health difficulties. Furthermore, service members with previous deployments are more frequently utilizing mental health care services in-theater.9 Using prevalence rates after deployment as a proxy for the mental health status of deployed personnel ignores a wealth of important information about the disease burden and resources necessary to care for deployed service members. A thorough evaluation of in-theater mental health status is vital to understanding force readiness, informing military medical planning, developing prevention efforts, and reducing potential risk. Therefore, this study examines the rates of mental health diagnoses in deployed active duty U.S. soldiers and examines related sociodemographic characteristics.

Methods

Participants

Data were drawn from the Army Analytics Person-Event platform of military personnel datasets, including the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) Contingency Tracking System (CTS), Active Duty Personnel Master files, and medical records from both the Military Health System (MHS) Data Repository and the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS10). The eligible study cohort consisted of 530,404 unique active duty service members in the U.S. Army who were deployed to an overseas contingency operations area between calendar years 2008 and 2013. This calendar timeline was selected to capture years of elevated deployments during contingency operations. This study assessed members of the Army, as this branch has consistently had the greatest number of personnel deployed and the highest percentage of active duty members diagnosed with a mental health condition over the past several years.3

Procedures

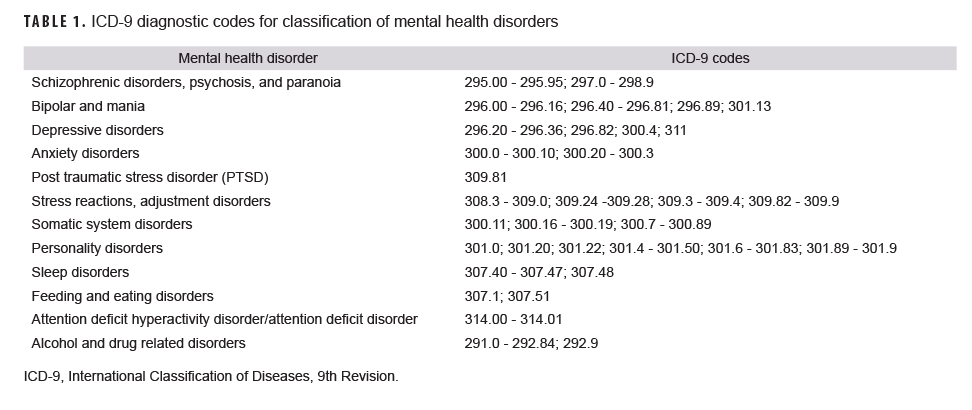

A CTS deployment event is defined as a service member who is physically located within a designated combat zone/area of operation or a member who has been specifically identified by their service as directly supporting the contingency operation’s mission. Overseas contingency operations are military operations designated by the Secretary of Defense in which armed forces are or may become involved in military actions, operations, or hostilities. All deployment event records are included in this study without any restrictions to a specific location and may involve combat or non-combat activities. Deployment records containing a begin date variable and end date variable were used to identify the date of the first deployment and periods of deployment from 1 January 2008 to 31 December 2013. Demographic variables, including military branch of service, were selected from the DMDC Personnel Master file corresponding to the date of first deployment. Encounter information from theater-based medical treatment facilities was retrieved from the TMDS for deployed soldiers identified during the study period. The International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision (ICD-9)12 diagnosis codes found in the primary or secondary diagnostic position of the TMDS medical record were used to create 12 different mental health categories for each soldier (Table 1). These categories were developed based on the grouping of diagnoses in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Fifth Edition (DSM-5)13 and then cross-referenced with the extant literature on military mental health to eliminate disorders with little relevance (e.g., autism spectrum disorder). To obtain counts of mental health disorders, dichotomous indicators (0: not diagnosed; 1: diagnosed) were set for each calendar year according to these mental health categorization definitions. A case was defined as any documentation of a mental health condition within the calendar year. Therefore, a soldier may appear within multiple diagnostic categories and multiple years.

Data analysis

Summary tables were generated, which captured counts by calendar year for deployment, demographic, and diagnostic variables. The unique number of deployed soldiers and person-years (p-yrs.) spent deployed were calculated by calendar year. Due to limitations of the data, diagnostic history could not be determined; thus, the case rates in this report may reflect incident, prevalent, or recurrent mental health disorders based on in-theater diagnostic coding. Due to the low frequency of some disorders, the rates are represented per 10,000 p-yrs. and suppressed for groups with less than 20 observations to ensure rate stability.14 Race/ethnicity data were most affected by this requirement, necessitating the exclusion of many rates due to low counts.

Results

Overall findings

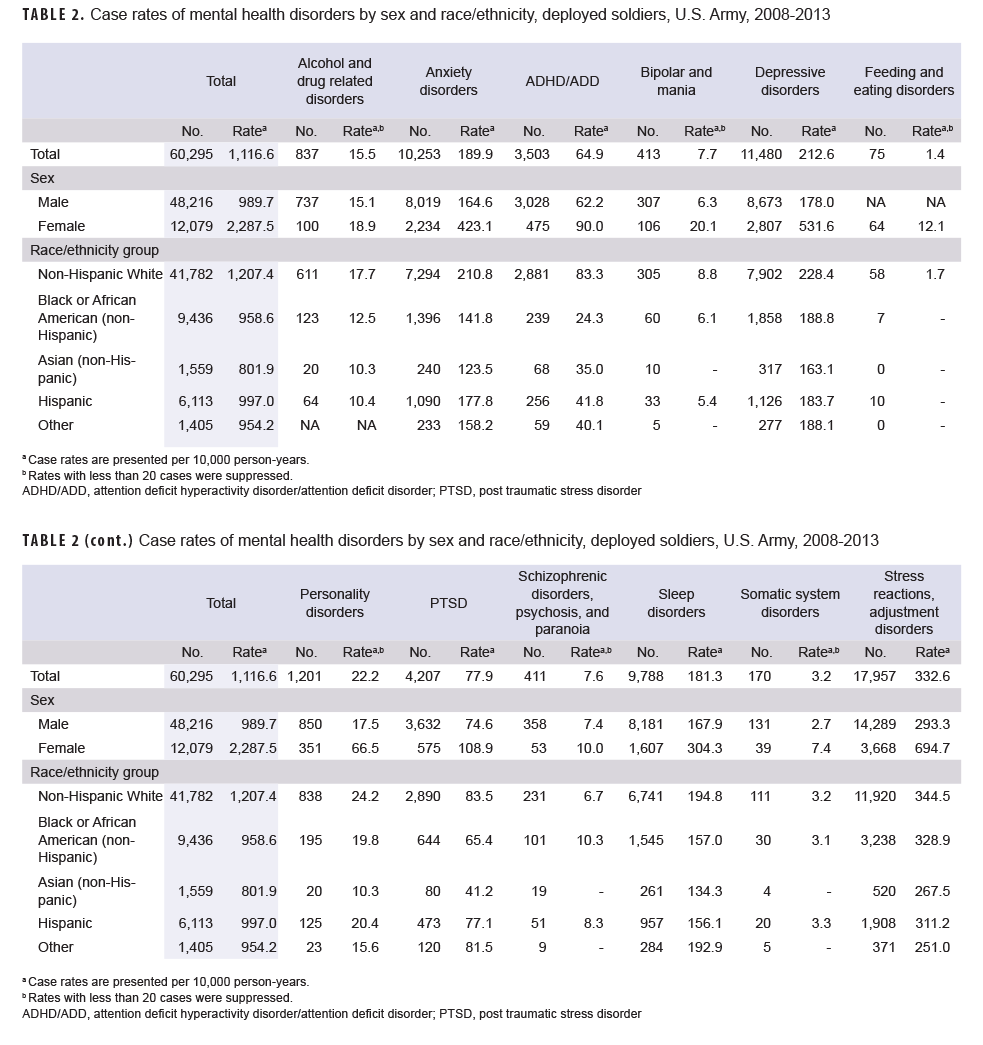

There was a case rate of 1,116.6 per 10,000 p-yrs. for any mental health disorder. Rates were lowest in 2008 (801.8/10,000 p-yrs.) and increased each year until peaking in 2012 (1,427.3/10,000 p-yrs.) before decreasing in 2013 (1,014.9/10,000 p-yrs.) (Table 2).

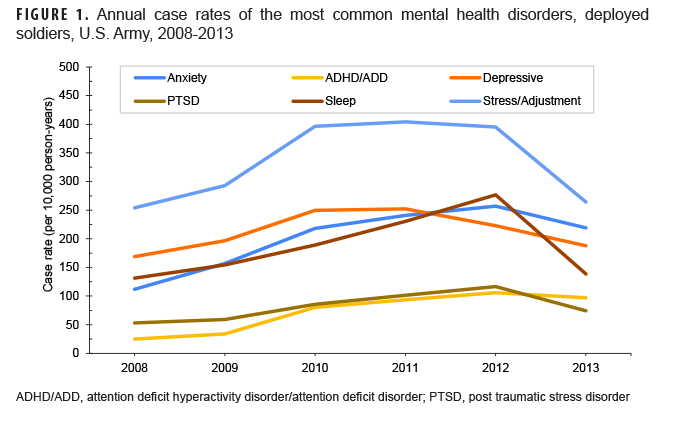

Examination of annual rates for the 12 diagnostic categories revealed that 6-year rates ranged from a low of 1.4/10,000 p-yrs. for eating/feeding disorders to a high of 332.6/10,000 p-yrs. for stress/adjustment disorders. Diagnostic categories could be roughly divided into those with high (>150/10,000 p-yrs.; sleep, anxiety, depression, stress/adjustment), moderate (50-149/10,000 p-yrs.; PTSD, ADHD/ADD), low (10-49/10,000 p-yrs.; alcohol/drug, personality), and very low (<10/10,000 p-yrs.; schizophrenia, bipolar, somatic, eating/feeding) rates. Rates of the 6 most common categories (high/moderate) tended to increase each year from 2008, peaking in 2012, and decreasing slightly in 2013 (Figure 1). The less frequent disorders tended to peak earlier (2009/2010) and have lower rates in ensuing years (Table 2).

Sex and race patterns in diagnostic categories

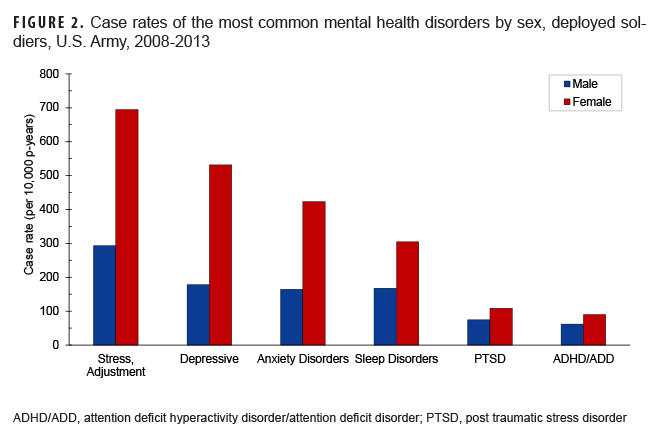

In each diagnostic category, female soldiers had a greater case rate than their male counterparts (Figure 2). This pattern was apparent in the 6-year rates and also for every annual comparison in which the count of diagnoses was 20 or more. Females demonstrated rates of diagnoses at least twice those of males for anxiety disorders, bipolar/mania, depressive disorders, personality disorders, somatic disorders, and stress reactions. Although some of these differences (e.g., depression, anxiety) reflect differences observed in the broader population,15,16 some differences stand in striking contrast to relative prevalence rates in the general population. For example, ADHD/ADD is diagnosed more frequently among males in the general population,17 but the rate among the deployed female soldiers in the present study was almost 50% higher than the rate among males. Similarly, although sex is generally unrelated to the prevalence of personality disorders,18 female soldiers in this study demonstrated a rate of personality disorder diagnoses almost 4 times their male counterparts.

The 6-year annual case rate of nearly all disorders was higher in non-Hispanic White soldiers than soldiers in other race/ethnicity groups. However, schizophrenic disorders, psychosis, and paranoia had a higher rate among Hispanic and Black/African American soldiers. There were no to negligible differences between the rates of somatic and stress-related disorders by race and ethnicity groups. Due to the low rate of feeding and eating disorders, comparative rate assessments by race cannot be made. Additionally, complete rates for individual race/ethnicity groups were available for the most common diagnoses. Rates for all disorders (i.e., anxiety disorders, ADHD/ADD, PTSD, depressive disorders, stress reactions/adjustment disorders) were highest among non-Hispanic White soldiers. Black/African American soldiers had the lowest rates of ADHD/ADD; Asian soldiers had the lowest rates of PTSD and anxiety, depressive, and sleep disorders; and patients with “other” race/ethnicity had the lowest rates of stress reactions/adjustment disorders.

Editorial Comment

The present study reports case rates of psychiatric disorders among U.S. Army personnel deployed to an overseas contingency operation area from 2008 through 2013. These rates were based on in-theater diagnostic codes, and thus represent incident, prevalent, or recurrent disease. Results highlight several important aspects regarding psychiatric disorders among military personnel. The most common disorders (>180/10,000 p-yrs.) were stress/adjustment, depression, anxiety, and sleep. In contrast, the study found very low case rates (<10/10,000 p-yrs.) of psychosis, bipolar, somatic, and eating disorders. These findings provide vital information in regard to the training and deployment of mental health providers and support assets into theater. Specifically, deploying mental health clinicians need to be trained and competent in the delivery of effective, short-term treatments for stress, anxiety, depression, and sleep disruptions. Future studies may examine the incidence of in-theater diagnoses, as well as the mental health and career trajectories of service members who receive in-theater diagnoses.

Consistent with the current findings, a previous study found rates of adjustment disorders, PTSD, anxiety, depression, and personality disorders to be higher among female recruits attending basic training;19 however, there were no noted differences between males and females in rates of alcohol abuse/dependence, schizophrenia, or other psychoses in this earlier study.19 The authors noted that the lack of difference in substance disorders may have been due to the stringent requirements against alcohol use during basic 19 training ;Among active duty service members receiving care from or reimbursed by the Military Health System between 2000 and 2011, female service members were diagnosed with adjustment, personality, depressive, and anxiety disorders at a higher rate than their male counterparts.20 In contrast to the current study’s findings, these researchers found that males were diagnosed more frequently with PTSD and alcohol/substance abuse. As in the current study, adjustment and depressive disorders were among the 2 most frequently diagnosed mental health disorders20 and reasons for mental health hospitalizations21 among service members in the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces. As noted above, some estimates suggest 7% of service members have depression and 11% experience PTSD following deployments.8 The observed rates of PTSD (0.8%) and depression (2.1%) in the present study were much lower.

As in prior studies of military medical records,20 adjustment disorders were diagnosed at a greater rate than other disorders. The case rate of stress/adjustment disorders (332.56/10,000 p-yrs or 3.3%) in the present sample is strikingly high given that estimates of adjustment disorder in the general population tend to be around 1%.22 It is likely that these rates reflect the high stress conditions inherent in deployments. However, it is possible some of these diagnoses may be given as a proxy for other diagnoses such as PTSD.23 However, an adjustment disorder diagnosis may be given prior to these diagnoses23 to reflect the acute period of stress experienced during a deployment, as adjustment disorder diagnoses are only appropriate for the 6-month period following the stressor. In addition to the potential stress of combat operations, it is likely some of these cases reflect difficulties in adjusting to deployment away from family and support systems as well as stress associated with problems “on the home front.” Additional research into the nature and reactions to different stressors while deployed is warranted. Further, better understanding of the stressors leading to significant adjustment problems could provide insight into the potential challenges of providing care to these service members when they return from deployment.

The present finding that female soldiers had 2.3 times the rate of diagnoses compared to male soldiers, considering all diagnostic groups and years, necessitates further study. Previous studies have found higher rates of psychiatric diagnosis among female service members,4,11 but the present results are notably different. For example, research indicates that male service members utilized more mental health services in proportion to their total outpatient and inpatient encounters for the middle (17.0%) and last 6 months (35.6%) of service compared to females (15.1% and 32.4%, respectively).24 Also, previous research found female service members were hospitalized for adjustment disorder, PTSD, depression, and bipolar disorder at higher rates, but male service members were hospitalized at greater rates for alcohol and substance use/abuse disorders.21 In the present study female soldiers had a 25% greater rate of diagnosis with alcohol/substance use disorders than male soldiers. Similarly, when considering the general population, the DSM-5 suggests that ADHD is 1.6 times more likely to be diagnosed in male adults than in female adults,13 but the observed rates of ADHD/ADD were nearly 45% times higher among female soldiers than their male counterparts. The findings from this study are consistent with those of Williams and colleagues25 who found female service members were medically evacuated from theater for a mental health reason at a rate 64% greater than that of their male counterparts. Understanding the reasons for the variability in rates in the deployed setting is critical to enhancing support for important sections of the DOD workforce, as close to 17% of the active duty DOD workforce identify as female.26

The nature of the present data suggests several possibilities for this difference that should be explored. First, deployed female soldiers may actually experience more mental health problems than their male peers. Among female service members, combat stress, military sexual trauma, family separation, and reintegration post-deployment are significant stressors27 that contribute to MH disorders.28-30 Second, female soldiers may be more likely than their male counterparts to seek help for mental health issues, an idea consistent with findings that female service members are more likely to receive MH care.31 Similarly, among active duty combat veterans screening positive for PTSD, major depressive disorder (MDD), or generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), women and veterans of color, compared to men and White veterans, were more interested in receiving care.32 Finally, health care providers may be more likely to psychiatrically diagnose deployed female soldiers compared to male soldiers due to sex-based biases. Implicit biases among primary care physicians resulted in female patients receiving less accurate diagnoses, made with less confidence, and less appropriate treatment recommendations than male patients.33 Addressing these possibilities would require unique policy, training, and clinical interventions.

Due to small case counts for some disorders, it was not possible to examine rates for individual race/ethnicity groups; rates were presented for the 6 most frequently diagnosed disorders for which the data permitted computation of all race/ethnicity groups. Non-Hispanic White soldiers were consistently diagnosed at greater rates than all other race/ethnicity groups, consistent with previous studies of military medical records.21,34.

Though the ability to analyze data from all Army personnel deployed to contingency operation areas during a 6-year period represents a notable strength of the current study, the reliance on medical record data from theater-based military treatment clinics and hospitals also creates some challenges. First, because the rates used in the present study require that a soldier seek treatment and have a mental health diagnosis coded into TMDS to be considered a case, it is inevitable that the case rate identified in the present study underestimates the actual rate of psychiatric illness. Although clinical diagnoses provide benefits relative to self-reported symptoms, the data offer no means to assess the validity of the diagnoses made or that diagnoses were reliably entered into the system and therefore available for analysis. Second, the diagnostic categories used in the present study are based on the ICD-9, which was in use within the military health care system at the time the data were collected. Results may differ with other diagnostic frameworks (e.g., DSM-5, ICD-10/11). Finally, the use of archived medical record data limits our ability to examine factors that may contribute to the reported results. This examination of rates defines a case as any documentation of a mental health condition within the calendar year in the primary or secondary diagnostic position, consistent with Hepner and colleagues.35 This definition was selected so that these rates may be as inclusive as possible. However, future studies may consider using other definitions with a more stringent criteria to increase confidence in the accuracy of the diagnosis (e.g., one primary inpatient diagnosis or two primary outpatient diagnoses documented within 30 days of each other34).

Despite the limitations inherent in working with archived medical records and unvalidated diagnoses, the present results provide vital insight into the mental health issues that arise and require treatment during deployments—conditions that providers should be prepared to diagnose and treat in the context of ongoing contingency operations. These rates provide a general framework for understanding case rates of mental health disorders among soldiers deployed into combat. Future studies should consider important demographic, psychological health, and calendar factors such as operations tempo that may influence rates of disorders. Additionally, future studies would be strengthened by consideration of pre-existing diagnostic status, which the present study was unable to examine. A more comprehensive understanding of the causes of the apparent differences across demographic groups will contribute to the development of new approaches and policies to better prepare, support, and treat soldiers during overseas deployments.

Author Affiliations

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, Maryland (Dr. Paxton Willing, Dr. Tate, Dr. Riggs); Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, Maryland (Dr. Paxton Willing); Psychological Health Center of Excellence, Silver Spring, Maryland (Mr. O’Gallagher, Dr. Evatt).

Disclaimer

The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Uniformed Services University, the Department of Defense, the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., or the Psychological Health Center of Excellence. Additionally, the authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Goode J, Swift JK. An empirical examination of stigma toward mental health problems and psychotherapy use in veterans and active duty service members. Mil Psychol. 2019;31(4):335-345.

- Elliott TR, Hsiao YY, Kimbrel NA, et al. Resilience, traumatic brain injury, depression, and posttraumatic stress among Iraq/Afghanistan war veterans. Rehabil Psychol. 2015;60(3):263-276. doi:10.1037/rep0000050

- Deployment Health Clinical Center. Mental Health Disorder Prevalence Among Active Duty Service Members in the Military Health System, Fiscal Years 2005–2016. Falls Church, Va.: Defense Centers of Excellence for Psychological Health and Traumatic Brain Injury Center, 2017.

- Hoge CW, Lesikar SE, Guevara R, et al. Mental disorders among U.S. military personnel in the 1990s: association with high levels of health care utilization and early military attrition. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1576-1583. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1576

- Hoge CW, Toboni HE, Messer SC, Bell N, Amoroso P, Orman DT. The occupational burden of mental disorders in the U.S. military: psychiatric hospitalizations, involuntary separations, and disability. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(3):585-591.

- Wilson ALG, Messer SC, Hoge CW. U.S. military mental health care utilization and attrition prior to the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Soc Psychiatry Epidemiol. 2009;44(6):473-481.

- Hoge CW, Auchterlonie JL, Milliken CS. Mental health problems, use of mental health services, and attrition from military service after returning from deployment to Iraq or Afghanistan. JAMA. 2006;295(9):1023-1032.

- Shen YC, Arkes J, Lester PB. Association between baseline psychological attributes and mental health outcomes after soldiers returned from deployment. BMC Psychol. 2017;5(1):32. doi:10.1186/s40359-017-0201-4

- Varga CM, Haibach MA, Rowan AB, Haibach JP. Psychiatric history, deployments, and potential impacts of mental health care in a combat theater. Mil Med. 2018;183(1-2): e77-e82. doi:10.1093/milmed/usx012

- Otto JL, Peters ZJ, O'Gallagher KG, et al. Evaluating measures of combat deployment for U.S. Army personnel using various sources of administrative data. Ann Epidemiol. 2019; 35:66-72.

- Ireland RR, Kress AM, Frost LZ. Association between mental health conditions diagnosed during initial eligibility for military health care benefits and subsequent deployment, attrition, and death by suicide among active duty service members. Mil Med. 2012;177(10):1149-1156. doi:10.7205/milmed-d-12-00051

- World Health Organization. International classification of diseases—Ninth revision (ICD-9). Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 1988;63(45):343-344.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th edition. American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Arias E, Tejada-Vera B. Deaths: Final data for 2018. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2021;69(13).

- McLean CP, Asnaani A, Litz BT, Hofmann SG. Gender differences in anxiety disorders: prevalence, course of illness, comorbidity and burden of illness. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45(8):1027-1035. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.03.006

- Marcus SM, Young EA, Kerber KB, et al. Gender differences in depression: findings from the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2):141-150. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2004.09.008

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942-8. doi:10.1176/ajp.2007.164.6.942

- Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):553-564.

- Monahan P, Hu Z, Rohrbeck P. Mental disorders and mental health problems among recruit trainees, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000-2012. MSMR. 2013;20(7):13-8.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Mental disorders and mental health problems, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000-2011. MSMR. 2012;19(6):11-7.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Summary of mental disorder hospitalizations, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000-2012. MSMR. Jul 2013;20(7):4-11.

- Patra BN, Sarkar S. Adjustment disorder: current diagnostic status. Indian J Psychol Med. 2013;35(1):4-9.

- Walter KH, Levine JA, Madra NJ, Beltran JL, Glassman LH, Thomsen CJ. Gender differences in disorders comorbid with posttraumatic stress disorder among U.S. Sailors and Marines. J Trauma Stress. 2022;35(3):988-998. doi:10.1002/jts.22807

- Uptegraft CC, Stahlman S. Variations in the incidence and burden of illnesses and injuries among non-retiree service members in the earliest, middle, and last 6 months of their careers, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000-2015. MSMR. 2018;25(6):10-17.

- Williams VF, Stahlman S, Oh GT. Medical evacuations, active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013-2015. MSMR. 2017;24(2):15-21.

- Department of Defense (DoD), Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Community and Family Policy (ODASD (MC&FP)). 2019 Demographics Profile of the Military Community. 2019. https://download.militaryonesource.mil/12038/MOS/Reports/2019-demographics-report.pdf

- Mattocks KM, Haskell SG, Krebs EE, Justice AC, Yano EM, Brandt C. Women at war: understanding how women veterans cope with combat and military sexual trauma. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(4):537-545. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.10.039

- Dutra L, Grubbs K, Greene C, et al. Women at war: implications for mental health. J Trauma Dissociation. 2010;12(1):25-37. doi:10.1080/15299732.2010.496141

- Maguen S, Luxton DD, Skopp NA, Madden E. Gender differences in traumatic experiences and mental health in active duty soldiers redeployed from Iraq and Afghanistan. J Psychiatr Res. 2012;46(3):311-316. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2011.11.007

- Skopp NA, Reger MA, Reger GM, Mishkind MC, Raskind M, Gahm GA. The role of intimate relationships, appraisals of military service, and gender on the development of posttraumatic stress symptoms following Iraq deployment. J Trauma Stress. 2011;24(3):277-286. doi:10.1002/jts.20632

- Hom MA, Stanley IH, Schneider ME, Joiner TE. A systematic review of help-seeking and mental health service utilization among military service members. Clin Psychol Rev. 2017;53:59-78. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.008

- Brown MC, Creel AH, Engel CC, Herrell RK, Hoge CW. Factors associated with interest in receiving help for mental health problems in combat veterans returning from deployment to Iraq. J Nerv. 2011;199(10).

- Bönte M, von dem Knesebeck O, Siegrist J, et al. Women and men with coronary heart disease in three countries: are they treated differently? Women's Health Issues. 2008;18(3):191-198. doi:10.1016/j.whi.2008.01.003

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Insomnia, active component, U.S. armed forces, January 2000-December 2009. MSMR. 2010;17(5):12-15.

- Hepner KA, Roth CP, Sloss EM, et al. Quality of Care for PTSD and Depression in the Military Health System: Final Report. Rand Health Q. Apr 2018;7(3):4.