ABSTRACT

The Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline (VA/DOD CPG) provides evidence-based management pathways to mitigate the negative consequences of common sleep disorders among service members (SMs). This retrospective cohort study estimated the incidence of chronic insomnia in active component military members from 2012 through 2021 and the percentage of SMs receiving VA/DOD CPG-recommended insomnia treatments. During this period, 148,441 incident cases of chronic insomnia occurred, with an overall rate of 116.1 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs). A sub-analysis of SMs with chronic insomnia diagnosed during 2019-2020 found that 53.9% received behavioral therapy and 72.7% received pharmacotherapy. As case ages increased, the proportion who received therapy decreased. Co-existing mental health conditions increased the likelihood of receiving therapy for insomnia cases. Clinician education about the VA/DOD CPG may improve utilization of these evidence-based management pathways for SMs with chronic insomnia.

What are the new findings?

From 2012 through 2021, the crude incidence rate of chronic insomnia among active component service members was 116.1 cases per 10,000 person-years, and the annual rate remained stable throughout the 10-year period. Among those diagnosed, 53.7% received behavioral therapy, the first line recommended insomnia treatment, and 72.7% received pharmacotherapy.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Insufficient sleep from chronic insomnia poses a direct threat to operational readiness due to impaired cognitive performance and increased musculoskeletal injury. The evidence-based management pathways outlined in the Department of Veterans Affairs and Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline should be promoted to mitigate the negative consequences of chronic insomnia.

BACKGROUND

Insomnia is characterized by a subjective perception of difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, dissatisfaction with sleep quantity or quality despite adequate opportunity, and subsequent daytime impairment. Chronic insomnia is defined as insomnia symptoms for at least 3 months duration and occurring at least 3 days per week, by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5),1 and the International Classification of Sleep Disorders, Third Edition.1,2

Insomnia is the most common sleep disorder in the U.S., with 20% to 30% of adults reporting at least 1 symptom of insomnia and an estimated 6% to 10% meeting diagnostic criteria for chronic insomnia.3,4 In a RAND report on sleep in the military, 48.6% of military personnel surveyed had poor sleep quality, and recent studies have reported the prevalence of insomnia as ranging from 4.5% to 22.8% among military personnel.5-9 In addition, studies suggest insomnia is a growing health threat to SMs. Department of Defense (DOD) medical surveillance data for the period 2000 through 2009 document a 19-fold increase in insomnia diagnoses over the 9-year period (crude incidence rate of insomnia increased from 7.2 to 135.8 cases per 10,000 person years [p-yrs]).10 Additionally, during Operation Iraqi Freedom (OIF), Operation Enduring Freedom (OEF), and Operation New Dawn (OND), diagnosis rates of insomnia increased dramatically in all branches of service.11,12

Sleep is vital to systemic physiology including metabolism, appetite regulation, immune and hormone function, as well as cardiovascular systems; it is critical to neurobehavior, cognitive performance, memory consolidation, and mood regulation.13 Not surprisingly, insomnia has been associated with higher rates of numerous physical and mental health conditions, as well as poor job performance and increased work-related injuries and accidents. Within the military, daytime fatigue due to poor sleep poses a direct threat to military operational readiness, as it is associated with negative health impacts such as impaired decision making and reaction time, decreased cognitive function, increased musculoskeletal injury, and decreased anaerobic and endurance performance.14-17 The impacts of insomnia can be severe, as evidenced by 2 separate fatal collisions of U.S. Navy ships in 2017 in which fatigue was cited as a contributing factor.18,19

The effects of poor sleep are well known to the DOD, and in 2019 a joint VA/DOD CPG was published to provide clinicians a framework by which to evaluate, treat, and manage the needs of patients with sleep disorders and promote greater sleep health among SMs.20 This study provides an update on the incidence of chronic insomnia among active component SMs between 2012 and 2021 and examines the implementation of the VA/DOD CPG recommendations among the active duty population diagnosed with chronic insomnia in the Military Health System (MHS) between 2019 and 2021.

METHODS

All data for this study were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). The DMSS contains comprehensive longitudinal data and links demographic information to direct and purchased health care encounters for active component SMs of the U.S. Armed Forces. Records of prescribed and dispensed sleep aid medications from the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) are also contained within DMSS. Data were also compiled from records of annual Periodic Health Assessments (PHAs), which include self-reports of a SM’s average sleep duration that capture the number of hours of sleep attained on most days during the 2 weeks prior to the PHA.

The overarching goals of this study were: 1) to determine the incidence of chronic insomnia among active component SMs by demographic and military characteristics; 2) to determine the proportion of incident chronic insomnia cases that received behavioral therapy (BT) or pharmacotherapy (PT) for treatment of chronic insomnia within 365 days after diagnosis; and 3) to determine the proportion of incident chronic insomnia cases that reported adequate sleep (7 or more hours/night) on a PHA administered before and after their chronic insomnia diagnoses. The surveillance period was 1 January 2012 through 31 December 2021. The surveillance population included all individuals who served at any time in the active component of the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps.

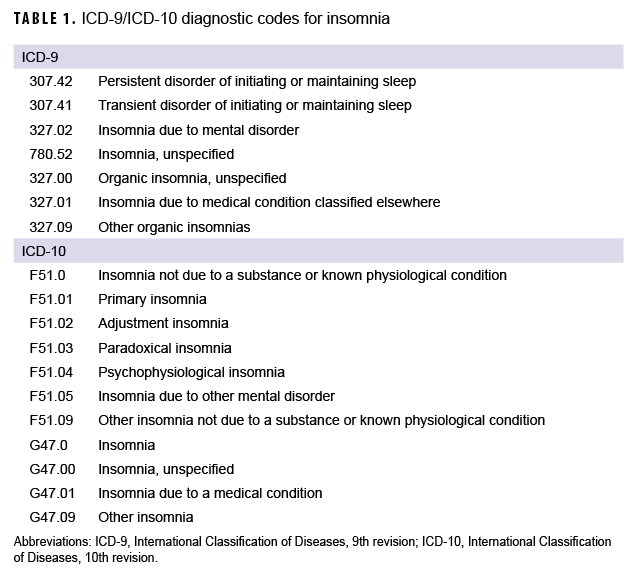

An incident case of insomnia was defined by records of at least 2 medical encounters (inpatient or outpatient) annotated with an International Classification of Diseases, 9th/10th revision (ICD-9 or ICD-10) diagnostic code for insomnia in any diagnostic position. Encounters had to be at least 90, but no more than 390, days apart (similar to the approach used by Bramoweth and colleagues to account for variability in annual appointment scheduling), and the incident date was defined as the first of the 2 qualifying encounters.21 The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes used to define a case of insomnia are listed in Table 1. Incidence rates were calculated as incident cases of chronic insomnia per 10,000 p-yrs of active component SMs. Individuals with a chronic insomnia diagnosis prior to 1 January 2012 were excluded and person-time was censored after the incident date of each incident case.

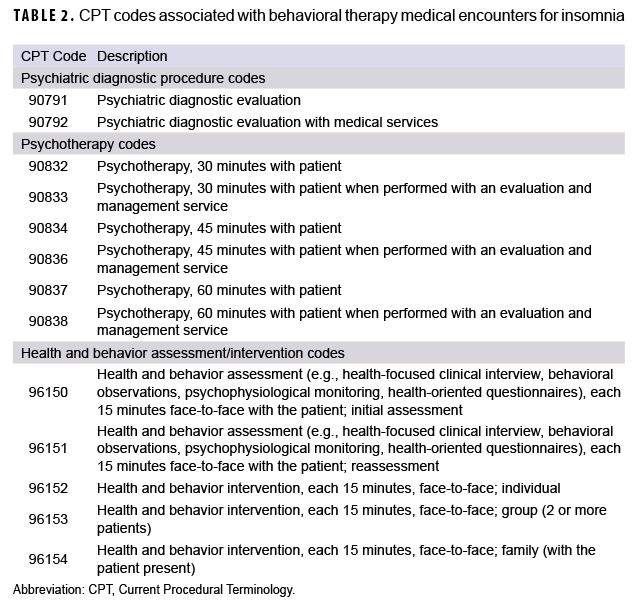

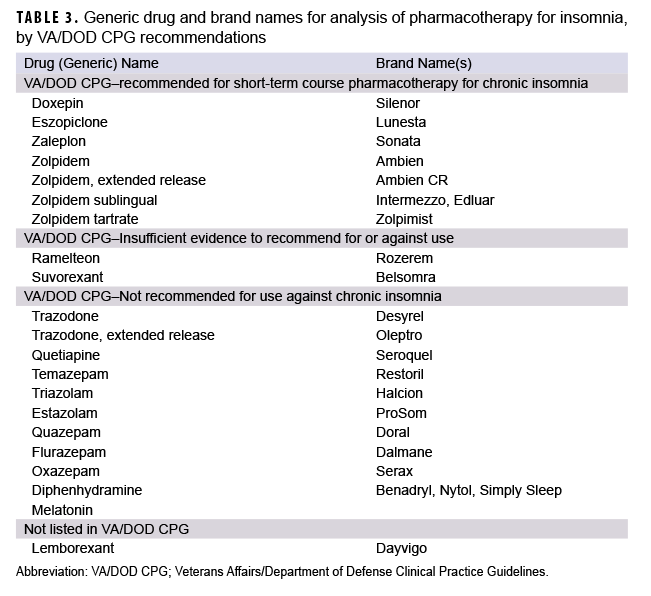

To assess the second objective, individuals with incident cases of chronic insomnia diagnosed during 2019 and 2020 were included in a subpopulation to determine the proportions that received BT or PT for treatment within 365 days after diagnosis. Individuals who did not have at least 1 year of follow-up time after their incident diagnosis were excluded. Baseline demographic, military, and clinical characteristics of cases were analyzed. Clinical characteristics included care type (Click to closeDirect CareDirect care refers to military hospitals and clinics, also known as “military treatment facilities” and “MTFs.”direct care in military hospitals or clinics or outsourced to Click to closeprivate sector careNetwork and non-network TRICARE-authorized civilian health care professionals, pharmacies, and suppliers.private sector care) and co-occurring ICD-10 diagnoses within the past year of traumatic brain injury (TBI) or a mental health condition commonly associated with insomnia symptoms, including anxiety, depression, substance use disorder, bipolar disorder, adjustment disorder, or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).22-26 The Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes used to define behavioral therapy medical encounters for insomnia are listed in Table 2. Brief Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (BBT-I) was defined as 1-4 sessions of BT, and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Insomnia (CBT-I) was defined as 5 or more sessions of BT. An outpatient medical encounter with an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for insomnia in any diagnostic position in combination with 1 of the CPT codes listed in Table 2 was considered BT for insomnia. A PDTS record for a dispensed sleep aid medication listed in Table 3 was considered PT for chronic insomnia. Both generic and brand names for each medication were searched in the PDTS record. All sleep aid medications included in the analysis, with the exception of the orexin receptor antagonist lemborexant (Dayvigo), were medications cited as reviewed PT interventions in the VA/DOD CPG methodology. Lemborexant was included in the analysis because it has the same mechanism of action as suvorexant (Belsomra), which was reviewed in the VA/DOD CPG methodology, but the Food and Drug Administration approval for use of lemborexant as a pharmacotherapy for insomnia was granted after the publication of the VA/DOD CPG.

For the third objective, PHA results were assessed from surveys administered before and after chronic insomnia diagnoses to determine the proportion of incident chronic insomnia cases self-reporting adequate sleep (7 or more hours/night). During the self-reported survey portion of the PHA, SMs are asked, “During the last 2 weeks, how many hours of sleep did you get on most days?” Available responses include “Less than 5 hours,” “5 to less than 7 hours,” “7 to 9 hours,” and “More than 9 hours.” In this analysis, responses were quantified as a dichotomous variable, with “Less than 5 hours” and “5 to less than 7 hours” considered inadequate sleep (less than 7 hours of sleep per night) and “7 to 9 hours” and “More than 9 hours” considered adequate sleep (7 or more hours of sleep per night). Individuals without a PHA record between 9 and 15 months after the chronic insomnia incident date were excluded. The percentage of those who reported adequate sleep was analyzed according to what type of treatment was received (BT, PT, or none).

RESULTS

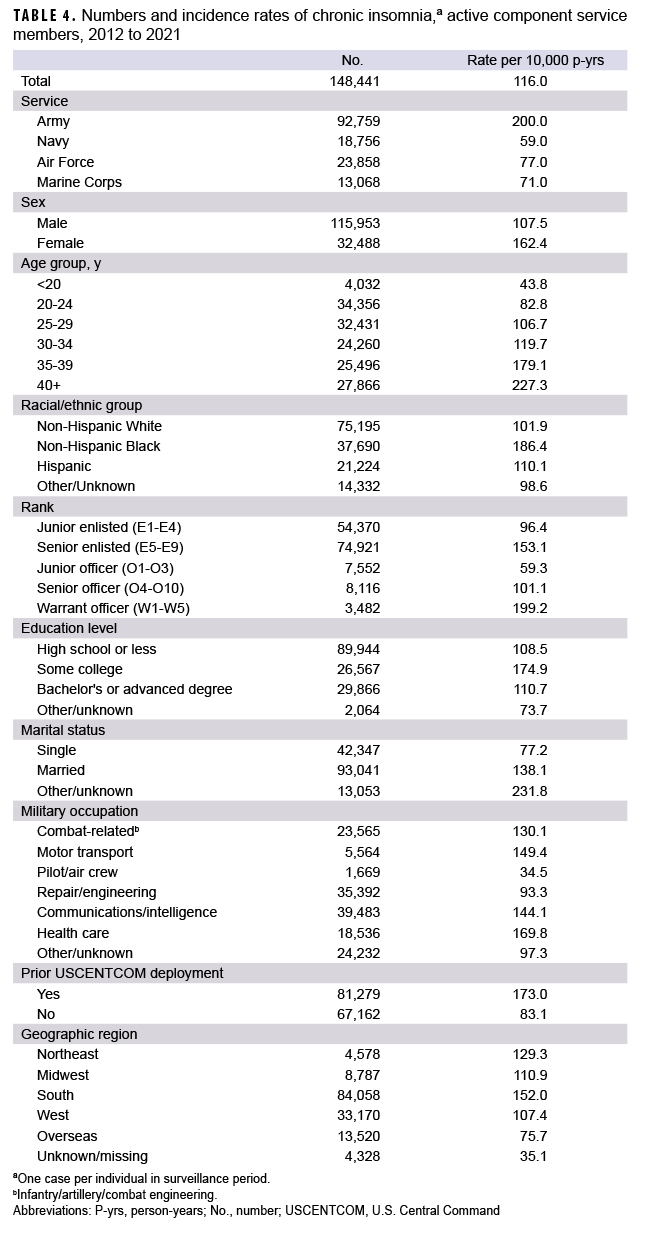

During the 10 years from 2012 through 2021, there were 148,441 incident diagnoses of chronic insomnia among active component SMs, with an overall crude incidence rate of 116.1 cases per 10,000 p-yrs (Table 4). The rates of incident diagnoses of insomnia remained relatively stable throughout the surveillance period (Figure 1); the highest annual rate was in 2016 at 134.0 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, and the lowest annual rate was in 2020 at 99.8 cases per 10,000 p-yrs. The Army's rates of chronic insomnia were consistently the highest among the services (Table 4), with an incidence rate more than twice the rate of any other service each year, peaking at 242.8 cases per 10,000 p-yrs in 2016 (data not shown).

Incidence increased linearly with age, with rates lowest among the youngest (<20 years) and highest among the oldest (>40 years) SMs. Incidence of chronic insomnia differed by sex as well as racial/ethnic group. Throughout the period, the incidence rate was 51% higher among females than males, and 69% to 89% higher for Non-Hispanic Black SMs compared to those of Non-Hispanic White, Hispanic, or Other/unknown race/ethnicity. Service members with a history of prior USCENTCOM deployment had an incidence rate 108% higher than those without prior USCENTCOM deployment (Table 4). The rate differences by age, sex, race and ethnicity, and prior USCENTCOM deployment persisted throughout the entire surveillance period (data not shown).

Treatment for chronic insomnia

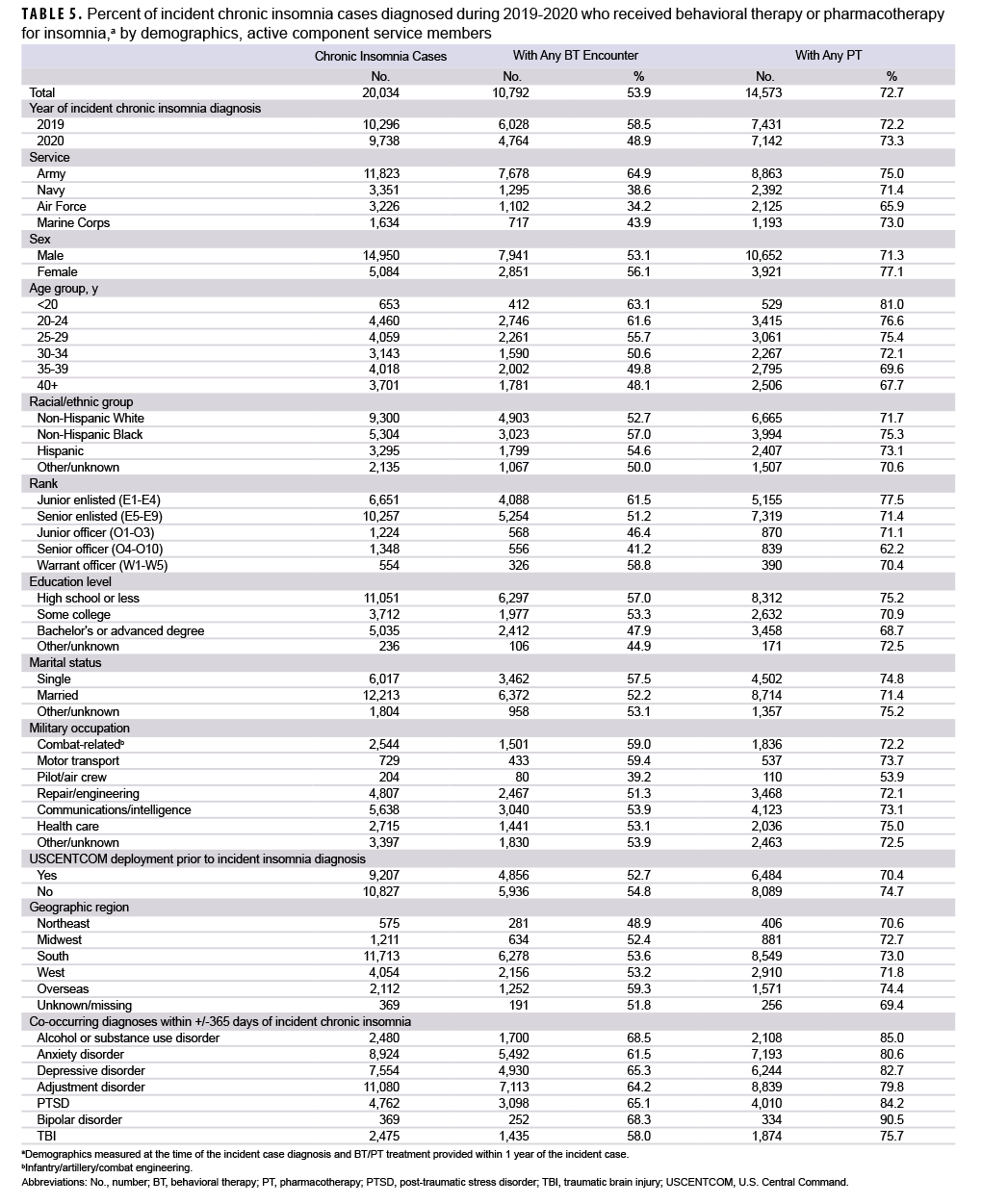

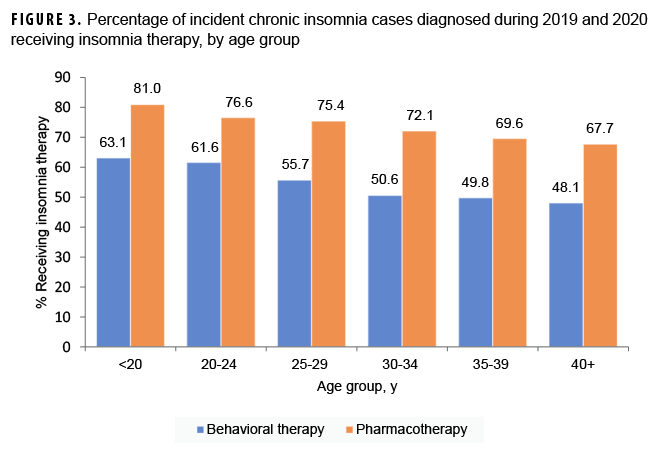

There were 20,034 individuals with incident chronic insomnia diagnoses between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2020. Of this subpopulation, 53.9% received BT and 72.7% received PT (Table 5). Some demographic and clinical subgroups were more likely to receive BT or PT for management of chronic insomnia. Across the services, the percentage of SMs receiving PT was similar; however, BT for insomnia was most common among Army SMs (Figure 2). The percentages of SMs who received therapy (BT or PT) decreased linearly with increasing age (Figure 3). A higher percentage of individuals with co-occurring mental health conditions received BT and PT compared to the overall population (Table 5). For example, 90.5% of individuals with co-occurring bipolar disorder received PT and 68.3% received BT, compared to 72.7% and 53.9% overall. A higher percentage of women (77.1%) received PT for insomnia management than men (71.3%); however, the percentages of those who received BT were similar for women and men.

No large differences (>5%) were seen in the percentage of SMs who received BT or PT by race/ethnicity or by history of prior USCENTCOM deployment. In addition, there was little difference by military occupation in percentages who received BT or PT, except for pilots/air crew, of whom only 39.2% received BT and 53.9% received PT.

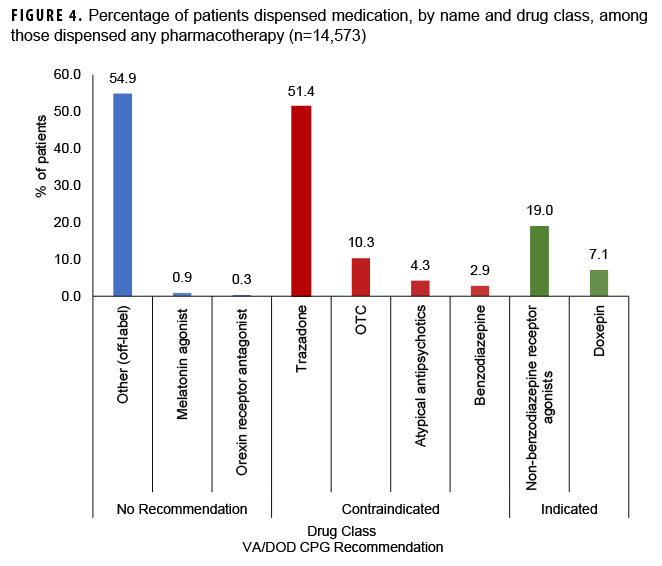

Of the individuals who received BT, 64.2% received BBT-I and 35.8% received CBT-I. Nearly all BT for insomnia management (97.2%) was provided in the direct care system (military hospitals or clinics). Figure 4 charts all dispensed PT based on the VA/DOD CPG recommendations.

Self-reported sleep duration before and after chronic insomnia diagnosis

The study cohort for this sub-analysis included 7,240 SMs; 12,794 individuals were excluded because they did not have a PHA record 9-15 months after their chronic insomnia incident date. On the PHA prior to diagnosis of chronic insomnia (baseline PHA), 961 SMs (13.3%) reported adequate (at least 7 hours) sleep on most days during the last 2 weeks, 5,785 SMs (79.9%) reported inadequate sleep (less than 7 hours per night), and 494 SMs (6.8%) did not have a baseline PHA (data not shown).

During a subsequent PHA performed 9-15 months after chronic insomnia diagnosis, 11.0% of the total 7,240 cases reported adequate sleep in the last 2 weeks. However, of the 79.9% who reported inadequate sleep on the baseline PHA, only 8.1% reported adequate sleep duration on the subsequent PHA. There was no difference in adequate sleep between SMs who received BT (10.4%) and PT (10.2%).

EDITORIAL COMMENT

This study examined the incidence of chronic insomnia in the last 10 years among active component military members along with the implementation of the 2019 VA/DOD CPG for the management of chronic insomnia in the MHS. The incidence rate of chronic insomnia remained relatively stable over the 10-year period. Consistent with prior studies, this analysis shows that certain demographic and clinical characteristics, including age, sex, and racial/ethnic group were associated with higher incidence rates of chronic insomnia.27-29 Among the services, the Army consistently had the highest rates of chronic insomnia (a finding consistent with prior reports).30 Additionally, the Army had higher rates of BT for treatment of chronic insomnia than all the other services. While the entire DOD has begun to prioritize optimal sleep as a means of enhancing SM safety and productivity, the Army has been at the forefront of service-wide educational programming on military-appropriate sleep practices. Additionally, the Army recently updated its Holistic Health and Fitness Manual to expand upon the importance of sleep and methods to improve sleep hygiene. These initiatives may help explain the higher incidence rates detected in the Army as well as the higher percentages of SMs who received BT for management.31

The incidence rate of chronic insomnia peaked in 2016, and there has been a continued downward trend in chronic insomnia diagnoses since 2016, which may reflect the lower operational tempo with the conclusions of OIF, OEF, and OND. The lowest incidence rate was in 2020; however, the incidence rate increased in 2021, which aligns with the higher prevalence of anxiety, depression, and insomnia during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic.32 COVID-19 led to unprecedented changes in how individuals live and work, and increased psychological stress due to health concerns, social isolation, financial hardship, disruption of education, and uncertainty about the future has had major impacts on mental health and sleep behavior globally.32 Further analysis of the incidence rate of chronic insomnia over time is warranted to better understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on sleep.

A sub-analysis of those with insomnia diagnosed in 2019 and 2020 shows, with increasing age, an inverse relationship between increasing incidence of chronic insomnia and decreasing percentages of individuals receiving therapeutics (BT or PT). This inverse relationship could be due to the fact this analysis did not evaluate a wide range of potential co-occurring health conditions that may contribute to insomnia symptoms, particularly among older individuals, such as chronic pain, tinnitus, cancer, diabetes, heart disease, and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). No differentiation was made between idiopathic insomnia and insomnia due to a comorbid condition with a direct link to some external factor such as medical illness, mental disorders, or other disruptive sleep disorder that prevents proper rest. The VA/DOD CPG-recommended treatments evaluated in this study specify management of idiopathic insomnia and these treatments may differ from the medical management needed to treat the underlying causes of health conditions associated with insomnia due to a comorbid condition. Therefore, this analysis may underestimate the percentage of older individuals receiving treatment for chronic insomnia because management for various comorbid conditions was not evaluated.

The findings of this study highlight a gap between the VA/DOD CPG recommendations for management of chronic insomnia and current MHS clinical practice. There was a nearly 20% difference in the percentage of SMs who received BT compared to PT, despite the guideline's recommendation of CBT-I as the first line treatment instead of PT. In a previous multiyear study of sedative hypnotic medications dispensed within the MHS, active duty SMs consistently demonstrated a higher prevalence of sedative hypnotic prescriptions than non-active duty SMs.33 Although the percentage of BT receipt increased for individuals with co-occurring mental health conditions, the percentage of PT receipt was also about 20% higher in these individuals. This is of concern because several VA/DOD CPGs published for management of mental health conditions recommend BT as either sole first line treatment or in conjunction with PT. The VA/DOD CPG acknowledges the potential for limited access to CBT-I, especially in rural or remote locations. The burden of frequent visits and potential perceived stigma also may affect SM willingness for BT participation.

Evaluating the effectiveness of BBT-I, provider-directed telehealth CBT-I, and self-directed internet-based programs in comparison to conventional CBT-I could potentially expand treatment capabilities and engender greater patient involvement in their own treatment. When considering PT for management of chronic insomnia, only 18% of SMs with incident cases of chronic insomnia in this study received sleep aid medications indicated for short-term pharmacotherapy as recommended in the VA/DOD CPG. The majority of medications dispensed for chronic insomnia were recommended against guideline use, suggesting that MHS clinical practice may need updating to align with the recommended management of chronic insomnia.

There are several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, chronic insomnia could have been misclassified, since it is captured by ICD-9 and ICD-10 diagnostic codes, which are susceptible to provider coding errors. As there is no ICD code specific to chronic insomnia, the diagnosis of chronic insomnia was inferred by documentation of multiple encounters for 1 individual associated with insomnia diagnosis during a 90 to 390-day period. This may have captured recurrent or episodic cases not fully meeting the chronic insomnia criteria. The decreased incidence rate of chronic insomnia in 2020 may be a function of the reduced medical service access and use during the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, as opposed to an actual decrease in incident chronic insomnia. In addition, the incident cases of chronic insomnia in 2021 may be under-captured because encounter data were not available throughout the entire 390-day period, as outlined in the case definition.

Second, BT used to treat potential co-occurring health conditions such as anxiety disorder, chronic pain, or tinnitus may have been misclassified as BT for insomnia treatment because the CPT codes do not differentiate between BT for insomnia or other conditions. Although the case definition required a diagnosis of insomnia in the encounter to count as BT for insomnia, in cases of multiple diagnoses, no distinction could be made. Additionally, access to BT may have been limited in 2020 due to COVID-19 pandemic mitigation measures. Third, medications available over the counter were likely under-captured in PDTS. Melatonin, diphenhydramine, and valerian are not recommended for management of chronic insomnia but can be purchased without a prescription.

Fourth, assessing outcome measures for the treatment of chronic insomnia with administrative data is challenging, as there is no ability to capture sleep quality or quantity with the existing diagnostic codes. While PHA data offer a glimpse of recent self-assessed sleep adequacy, the PHA does not contain validated sleep screening questions; therefore, it is not an adequate measure of sleep self-assessment and cannot assess treatment effect on overall sleep improvement. Nevertheless, the strength of the study is its large population-based cohort that comprehensively captured a wide range of longitudinal data and linked demographic information to both direct and Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care medical encounters as well as pharmacy services, demonstrating the management of chronic insomnia within the MHS.

Poor sleep affects the health and performance of individual SMs and poses a threat to military operational readiness. The evidence-based management pathways established in the VA/DOD CPG for chronic insomnia aim to mitigate the negative consequences of this common sleep disorder. Clinician education is necessary to promote the implementation of the VA/DOD CPG management pathways for SMs with chronic insomnia. A prospective assessment of both the implementation of these recommendations and the sleep outcomes from recommended treatment is needed to better measure improved sleep duration and quality and more clearly assess the effectiveness of chronic insomnia management among military SMs.

Author Affiliations

Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Lt Col Hsu); AFHSD, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Stahlman, Dr. Fan, CAPT Wells).

Disclaimer

The content of this manuscript is the sole responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or policies of the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences, Defense Health Agency, Department of the Air Force, Department of Defense, or the United States Government.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

- American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The International Classification of Sleep Disorders–Third Edition (ICSD-3). Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014.

- Buysse DJ. Insomnia. JAMA. 2013;309(7):706-716. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.193

- Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia. Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1129-1141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60750-2

- Troxel WM, Shih RA, Pedersen ER, et al. Sleep in the military: promoting healthy sleep among U.S. service members. Rand Health Q. 2015;5(2):19.

- Department of Defense. Health of the Force 2020. Published online February 1, 2022. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2022/02/01/DoD-Health-of-the-Force-2020. Accessed August 9, 2022

- Taylor DJ, Pruiksma KE, Hale WJ, et al. Prevalence, correlates, and predictors of insomnia in the US Army prior to deployment. Sleep. 2016;39(10):1795-1806. doi:10.5665/sleep.6156

- Markwald RR, Carey FR, Kolaja CA, et al. Prevalence and predictors of insomnia and sleep medication use in a large tri-service U.S. military sample. Sleep Health. 2021;7(6):675-682. doi:10.1016/j.sleh.2021.08.002

- Klingaman EA, Brownlow JA, Boland EM, et al. Prevalence, predictors and correlates of insomnia in U.S. army soldiers. J Sleep Res. 2018;27(3):e12612. doi:10.1111/jsr.12612

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Insomnia, active component, U.S. armed forces, January 2000–December 2009. MSMR. 2010;17(5):12-15.

- Mysliwiec V, Gill J, Lee H, et al. Sleep disorders in U.S. military personnel. Chest. 2013;144(2):549-557. doi:10.1378/chest.13-0088

- Seelig AD, Jacobson IG, Smith B, et al. Sleep patterns before, during, and after deployment to Iraq and Afghanistan. Sleep. 2010;33(12):1615-1622. doi:10.1093/sleep/33.12.1615

- Consensus Conference Panel, Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G. et al. Joint Consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and Sleep Research Society on the recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: methodology and discussion. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(08):931-952. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.4950

- Alhola P, Polo-Kantola P. Sleep deprivation: impact on cognitive performance. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2007;3(5):553-567.

- Rolls A, Colas D, Adamantidis A, et al. Optogenetic disruption of sleep continuity impairs memory consolidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108(32):13305-13310. doi:10.1073/pnas.1015633108

- Killgore WDS. Effects of sleep deprivation on cognition. In: Progress in Brain Research. Vol 185. Elsevier; 2010:105-129. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53702-7.00007-5

- Lisman P, Ritland BM, Burke TM, et al. The association between sleep and musculoskeletal injuries in military personnel: a systematic review. Mil Med. Published online May 11, 2022:usac118. doi:10.1093/milmed/usac118

- Department of the Navy Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. Report on the Collision Between USS Fitzgerald (DDG 62) and Motor Vessel ACX Crystal. October 23, 2017. https://www.secnav.navy.mil/foia/readingroom/HotTopics/CNO%20USS%20Fitzgerald%20and%20USS%20John%20S%20McCain%20

Response/CNO%20USS%20Fitzgerald%20and%20USS%20John%20S%20McCain%20Response.pdf. Accessed August 11, 2022.

- National Transportation Safety Board. Collision Between US Navy Destroyer John S McCain and Tanker Alnic MC, Singapore Strait, 5 Miles Northeast of Horsburgh Lighthouse, August 21, 2017. Marine Accident Report NTSB/MAR-19/01. Accessed August 11, 2022. https://www.ntsb.gov/investigations/AccidentReports/Reports/MAR1901.pdf

- The Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder and Obstructive Sleep Apnea Work Group. VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs: Washington, DC, USA; 2019.

- Bramoweth AD, Tighe CA, Berlin GS. Insomnia and insomnia-related care in the Department of Veterans Affairs: an electronic health record analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8573. Published August 13, 2021. doi:10.3390/ijerph18168573

- Montgomery MC, Baylan S, Gardani M. Prevalence of insomnia and insomnia symptoms following mild-traumatic brain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2022;61:101563. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2021.101563

- Roth T. Insomnia: definition, prevalence, etiology, and consequences. J Clin Sleep Med. 2007;3(5 Suppl):S7-S10.

- Morin CM, Benca R. Chronic insomnia [published correction appears in Lancet. 2012 Apr 21;379(9825):1488]. Lancet. 2012;379(9821):1129-1141. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60750-2

- Burman D. Sleep disorders: insomnia. FP Essent. 2017;460:22-28.

- Lind MJ, Brown E, Farrell-Carnahan L, et al. Sleep disturbances in OEF/OIF/OND veterans: associations with PTSD, personality, and coping. J Clin Sleep Med. 2017;13(2):291-299. Published February 15, 2017. doi:10.5664/jcsm.6466

- Foley DJ, Monjan AA, Brown SL, et al. Sleep complaints among elderly persons: an epidemiologic study of three communities. Sleep. 1995;18(6):425-432. doi:10.1093/sleep/18.6.425

- Morin CM, Jarrin DC, Ivers H, et al. Incidence, persistence, and remission rates of insomnia over 5 years. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2018782. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18782

- Chen X, Wang R, Zee P, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in sleep disturbances: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA). Sleep. 2015;38(6):877-888. doi:10.5665/sleep.4732

- Moore BA, Tison LM, Palacios JG, Peterson AL, Mysliwiec V. Incidence of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea in active duty United States military service members. Sleep. 2021;44(7):zsab024. doi:10.1093/sleep/zsab024

- Holistic Health and Fitness (FM 7-22). Headquarters, Dept of the Army. 8 October 2020. Field Manual 7-22. Accessed October 28, 2022. https://armypubs.army.mil/epubs/DR_pubs/DR_a/ARN30964-FM_7-22-001-WEB-4.pdf

- Morin CM, Bjorvatn B, Chung F, et al. Insomnia, anxiety, and depression during the COVID-19 pandemic: an international collaborative study. Sleep Med. 2021;87:38-45. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2021.07.035

- Thelus Jean R, Hou Y, Masterson J, Kress A, Mysliwiec V. Prescription patterns of sedative hypnotic medications in the military health system. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019;15(6):873-879.