Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is characterized by symptoms associated with dysfunction of the esophagus due to chronic mucosal eosinophilia and inflammation.1,2 Environmental and food allergens, enhanced type 2 helper T cell (Th2) activity, genetic predisposition, impaired esophageal epithelial barrier, and potential for fibrosis have all been implicated in EoE.1,3 Predominant symptoms in adults include dysphagia and food impaction, with 1 systematic review indicating symptom prevalence ranging from 29-100% and 25-100% respectively.1,4 Treatment is focused on the triad of dietary modifications, medications, and dilation to control symptoms and restore normal esophageal function.1

The reported prevalence of EoE has been increasing worldwide, with a recent meta-analysis estimating 34.2 cases per 100,000 persons.5 Subgroup analysis of North American adults reveals similar rates, at 31.9 cases per 100,000 adults, with individual studies on U.S. adults ranging from 9.45 to 58.9 cases per 100,000.5 The incidence of EoE has been increasing over the past several decades, and while this phenomenon is at least partially due to increased awareness and interest in the condition, some studies report that the rate of EoE has disproportionately risen with the increased rate of biopsies during the same study periods, suggesting a true increase in EoE.6,7

EoE is more common in men, those of White race/ethnicity, and those with atopic disease.8 It can present at any age, but the majority of cases occur among children, adolescents, and adults under 50 years.8 Because the majority of the active component military is comprised of White men under 50 years, EoE may be an important contributor to the burden of disease in this population. This study examines the incidence of EoE among active component service members (ACSM) to characterize the disease impact on this population, and evaluate change in the incidence over the study period. EoE is disqualifying for accession into military service due to potential for uncontrolled symptoms or food impactions in austere or medically limited environments; consequently, new service members should not have a diagnosis of EoE.9

Methods

The surveillance period covered January 1, 2009 through December 31, 2021. The surveillance population included all ACSM of the Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps. The data used to determine incident cases of EoE were derived from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which documents both ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System) clinics and hospitals.

An incident case of EoE was defined by 2 outpatient medical or Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS) encounters within 365 days of each other or 1 hospitalization with a diagnosis of EoE in any diagnostic position (ICD-9: 530.13, ICD-10: K20.0). The incident date was defined as the date of the first hospitalization or outpatient medical encounter that included a defining diagnosis of EoE. ICD codes were used to define cases because histologic data were not available and previous studies indicated high specificity of the ICD codes.10,11

Results

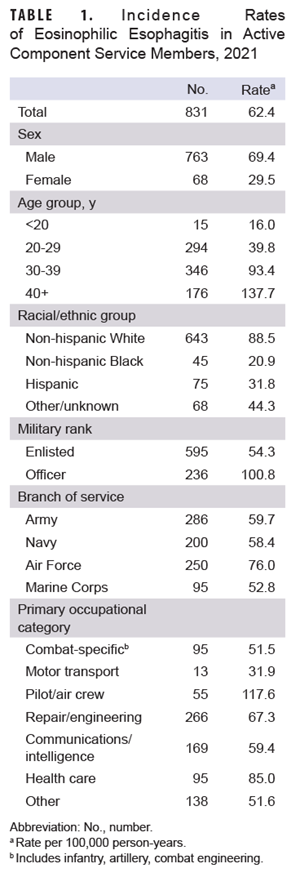

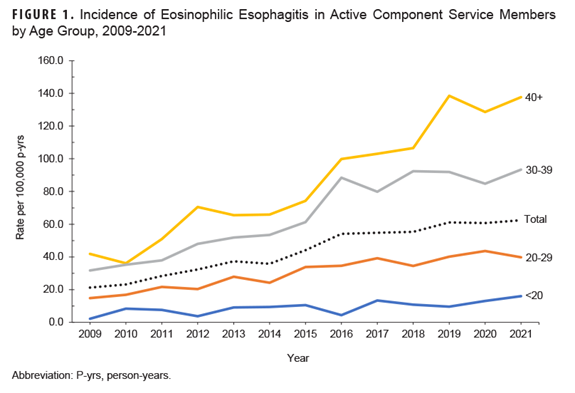

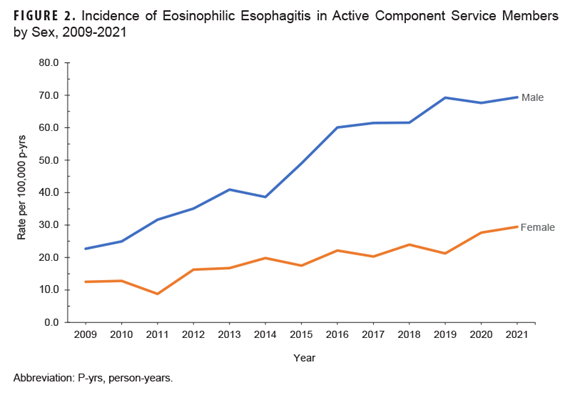

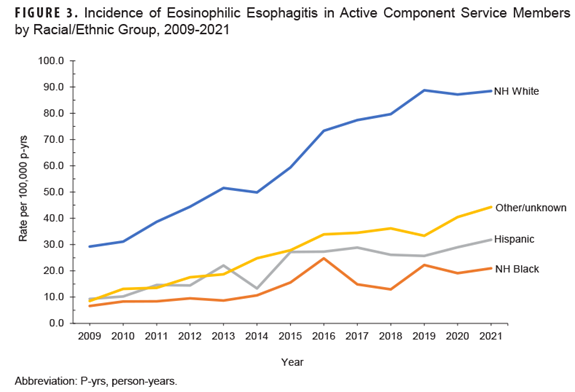

The 7,592 incident cases of EoE among ACSM during the 2009 to 2021 surveillance period resulted in an overall incidence rate of 43.5 cases per 100,000 person years (p-yrs). Crude (i.e., unadjusted) incidence rates for selected covariates in 2021 are shown in Table 1. In 2021, the incidence rate of EoE among men was more than twice than the rate among women. The rate of EoE increased with each older age category, with the highest rates in those over the age of 40. Among racial/ethnic groups, the highest rate of EoE was among non-Hispanic Whites. Service members of the Air Force had the highest rate, and those in the Marine Corps had the lowest, while the rate among officers was almost twice the rate for enlisted members. Pilots and aircrew had the highest rates among occupation groups, followed by health care workers.

Incidence rates steadily climbed throughout the surveillance period, from 21.2 cases per 100,000 in 2009 to 62.4 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2021 (Figure 1).

Rates among the 2 oldest age categories increased at a faster rate than service members in their 20s (Figure 1). Incidence rates among men increased at a higher rate compared to rates among women (Figure 2).

In addition, the incidence rate increased most notably among non-Hispanic Whites during the surveillance period (Figure 3).

Discussion

The results of this study show a steady increase in the incidence of EoE among ACSM between 2009 and 2021. Previously published literature has indicated that the incidence and prevalence of other Th2 type allergic and atopic diseases are increasing among ACSMs.12 Although there is variability in methodology, multiple studies demonstrate the increasing incidence and prevalence of EoE in a variety of populations studied worldwide.13-15 The increasing trend is largely unexplained and likely not due to increase disease recognition alone.6,7,14

Although the incidence rates presented in this study are in accordance with findings from some studies in the U.S. adult population with similar methodology, these rates are higher compared to other studies in the U.S. and Europe that used more stringent case definitions, such as pathologist-validated reports.13,15-17 The demographic risk factor results of this study are consistent with published literature, with higher incidence rates of EoE in men, non-Hispanic Whites, and adults in their 30s and 40s.18 ACSMs are predominantly younger (55% are in their 20s), White (69%), and male (83%), which may account for the higher rates in this study compared to others. With universal health care in the military, more members may have access to care than in other U.S. studies, which could also account for the increased rates identified in this study. Military members may seek medical care towards the end of the career to prevent career-ending medical evaluations, which could contribute to the highest rates within the oldest age range. This study did not attempt to identify specific occupational, environmental, or demographic risk factors among ACSM, which would require additional analyses.

As with all studies that utilize administrative data, this study is reliant upon the coding of medical encounters. Incident cases in this study may have been ruled out later by biopsy, which would have overestimated incidence rates. A full review of pathology reports or chart reviews would need to be conducted to validate all cases. A prior study, however, found that the use of the ICD-9 code (530.13) is very specific for EoE (99% specificity), which would suggest that most cases identified by ICD codes are true cases.10

The incidence of EoE among ACSM should continue to be monitored, as the rate did not appear to plateau during the surveillance period despite a reduction during the first 21 months of the COVID-19 pandemic, when medical care was less available for non-urgent conditions. As more ACSM are diagnosed with EoE, complications from treatment and need for periodic endoscopic interventions will increase. Management options are currently limited, with only 1 FDA-approved biologic, dupilumab, for the treatment of EoE—and ongoing biologic therapy is disqualifying for military service. Other treatments include proton pump inhibitors and topical “swallowed” corticosteroids (asthma inhalers) that are used off-label for EoE.19 Strictures require endoscopic dilation, which has associated risks of anesthesia and procedural complications. More studies are needed to evaluate specific and modifiable exposures such as pollutants, diet, infectious diseases, and environmental allergens that may be associated with EoE.20-22

Author Affiliations

Office of the Air Force Surgeon General, Falls Church, VA (Dr. Baldovich); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Defense Health Agency, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Stahlman); Department of Medicine, Allergy & Immunology, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, MD (Dr. Lee).

References

- Furuta GT, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic esophagi-tis. NEJM. 2015;373(17):1640-1648. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1502863

- Muir A, Falk GW. Eosinophilic esophagi-tis: a review. JAMA. 2021;326(13):1310-1318. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.14920

- Merves J, Muir A, Modayur Chandramou-leeswaran P, Cianferoni A, Wang ML, Spergel JM. Eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2014;112(5):397-403. doi:10.1016/j. anai.2014.01.023

- Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Collins MH, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in children and adults: a systematic review and consensus recommendations for diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol. 2007;133(4):1342-1363. doi:10.1053/j.gas-tro.2007.08.017

- Navarro P, Arias Á, Arias-González L, Laserna-Mendieta EJ, Ruiz-Ponce M, Lucendo AJ. System-atic review with meta-analysis: the growing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis in children and adults in population-based studies. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49(9):1116-1125. doi:10.1111/apt.15231

- Dellon ES, Erichsen R, Baron JA, et al. The in-creasing incidence and prevalence of eosinophilic oesophagitis outpaces changes in endoscopic and biopsy practice: national population-based estimates from Denmark. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41(7):662-670. doi:10.1111/apt.13129

- Warners MJ, de Rooij W, van Rhijn BD, et al. Incidence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the Nether-lands continues to rise: 20-year results from a nationwide pathology database. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;30(1). doi:10.1111/nmo.13165

- Dellon ES. Epidemiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2014;43(2):201-218. doi:10.1016/j.gtc.2014.02.0029. Department of Defense. Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services (DOD Instruction 6130.03). 2011.

- Department of Defense. Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services (DOD Instruction 6130.03). 2011.

- Rybnicek DA, Hathorn KE, Pfaff ER, Bulsiewicz WJ, Shaheen NJ, Dellon ES. Administrative coding is specific, but not sensitive, for identifying eosinophilic esophagitis. Dis Esophagus. 2014;27(8):703-708. doi:10.1111/dote.12141

- Robson J, Korgenski K, Parsons K, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of administrative medical coding for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2019;69(2):e49-e53. doi:10.1097/mpg.0000000000002340

- Lee RU, Stahlman S. Increasing incidence and prevalence of food allergies in the US military, 2000-2017. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8(1):361-363. doi:10.1016/j.jaip.2019.08.031

- de Rooij WE, Barendsen ME, Warners MJ, et al. Emerging incidence trends of eosinophilic esophagitis over 25 years: results of a nationwide register-based pathology cohort. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2021;33(7):e14072. doi:https://doi. org/10.1111/nmo.14072

- Kumar S, Choi SS, Gupta SK. Eosinophilic esophagitis: current status and future directions. Pediatr Res. 2020;88(3):345-347. doi:10.1038/s41390-020-0770-4

- Dellon ES, Hirano I. Epidemiology and natural history of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Gastroenterol. 2018;154(2):319-332.e3. doi:10.1053/j.gas-tro.2017.06.067

- Parton J, Yang X, Eke R. S503 examining the diagnostic pattern of eosinophilic esophagitis among Medicaid enrollees in the deep south U.S. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10S):e356-e357. doi:10.14309/01.ajg.0000858652.02201.c4

- Dellon ES, Jensen ET, Martin CF, Shaheen NJ, Kappelman MD. Prevalence of eosinophilic esophagitis in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12(4):589-596.e1. doi:10.1016/j. cgh.2013.09.008

- Lipowska AM, Kavitt RT. Demographic features of eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastrointest Endosc Clin N Am. 2018;28(1):27-33. doi:10.1016/j. giec.2017.07.002

- Dellon ES, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, et al. Dupilumab in adults and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis. NEJM. 2022;387(25):2317-2330. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2205982

- Jensen ET, Dellon ES. Environmental factors and eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;142(1):32-40. doi:10.1016/j. jaci.2018.04.015

- Shah MZ, Polk BI. Eosinophilic esophagitis: the role of environmental exposures. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2022;42(4):761-770. doi:10.1016/j. iac.2022.05.006

- Angerami Almeida K, de Queiroz Andrade E, Burns G, et al. The microbiota in eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;37(9):1673-1684. doi:https://doi. org/10.1111/jgh.15921