What Are the New Findings?

During the surveillance period, 210,914 incident cases of SSTIs affected 174,893 service members, resulting in 307,160 health care encounters and 14,819 hospital bed days. Those most commonly affected were the youngest service members, recruits/trainees, and junior enlisted personnel. The annual incidence rates have fallen in recent years, but the burden of disease is still significant.

What is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Although most SSTIs can be treated and cured with antibiotics, the health care burden presented by these relatively common conditions detracts from the availability of service members for readiness training and for operational duties.

Abstract

During 1 Jan. 2016–30 Sept. 2020, there were 210,914 incident cases of skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) among active component U.S. military members, corresponding to a crude overall incidence rate of 352.8 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs). An additional 4,250 cases occurred in theaters of operations (251.0 per 10,000 p-yrs). Of the total incident SSTI diagnoses, 64.5% were classified as cellulitis/abscess, 30.0% were "other SSTIs" (e.g., folliculitis, impetigo), 5.3% were carbuncles/furuncles, and 0.2% were erysipelas. Crude annual incidence rates declined by 21.9% over the surveillance period. In general, higher rates of SSTIs were associated with younger age, recruit/trainee status, and junior enlisted rank. A total of 174,893 service members were treated for SSTIs, which accounted for 307,160 medical encounters and 14,819 hospital bed days. SSTIs in the military are associated with significant operational and health care burden. Strategies for the prevention, early diagnosis, and definitive treatment of SSTIs are warranted, particularly in initial military training and operational settings associated with increased risk of infection.

Background

Skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) result from microbial breaches of skin and its supporting structure. SSTIs have diverse clinical manifestations, but most frequently present as abscess (a tender mass containing cells, microbes and pus) or cellulitis (an area of redness and swelling involving deeper skin tissue). Less frequent clinical outcomes such as impetigo and folliculitis present as pustules or vesicles forming on skin surfaces or in hair follicles. When an initial occurrence of folliculitis penetrates deeper into skin tissue, furuncles and carbuncles ("boils") may develop and lead to tender, swollen pustules. Among otherwise healthy persons, SSTIs are generally mild and resolve after a short course of antibiotics and/or drainage.

SSTIs are common in both military and nonmilitary populations. In the military, rates of SSTIs are highest among recruits/trainees due to an increased prevalence of SSTI risk factors (e.g., crowding, infrequent hand washing/bathing, skin abrasions and trauma, and environmental contamination) in the military training environment. These factors favor the acquisition and transmission of Staphylococcus spp and Streptococcus spp, the major causative agents of SSTIs, and can result in outbreaks of disease in military trainees.1-3

SSTIs in military personnel are rarely associated with severe clinical outcomes. However, they are a major cause of infectious disease morbidity and impose a significant operational and health care burden on the Military Health System (MHS). The epidemiology of SSTIs in the MHS has been described previously.4,5 From 2013 through 2016, the overall incidence of SSTI among active component U.S. military members was 558.2 per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs), approximately 20% higher than that of a similarly aged, non-military population in the U.S.6 Notably, annual incidence rates over the 4-year period declined by 46.6%, mirroring trends of declining7,8 or stabilizing9 rates of SSTIs reported from U.S. civilian hospitals.

This report summarizes the frequencies, rates, and trends of incident diagnoses of SSTIs, overall and by type, among members of the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces from 1 Jan. 2016 through 30 Sept. 2020. In particular, installation-specific SSTI rates for each service's recruit/trainee population, the military group at highest risk for infection, are reported.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2016 to 30 Sept. 2020. The surveillance population included all members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps who served in the active component at any time during the surveillance period. The data used in this analysis were derived from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which maintains electronic records of all actively serving U.S. military members' hospitalizations and ambulatory visits in U.S. military and civilian (contracted/Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care through the MHS) medical facilities worldwide. Diagnoses recorded in the combat theater of operations were derived from records documented in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS). TMDS records were only included if they occurred during an operational deployment.

For surveillance purposes, cases of SSTI were identified from records of hospitalizations, ambulatory visits, and in-theater medical encounters that included diagnostic codes (ICD-9 and ICD-10) specific for SSTI (Table 1). Incident cases of SSTI were defined by hospitalization records with case-defining diagnostic codes in the primary or secondary diagnostic position or by ambulatory or in-theater visit records with case-defining diagnostic codes in the first diagnostic position. An individual could account for multiple incident cases (i.e., recurrent SSTI) if there were more than 30 days between the dates of consecutive incident case-defining encounters. Rates of SSTIs diagnosed in inpatient or outpatient settings were calculated using non-deployed person time. SSTIs occurring during deployments were analyzed separately from inpatient and outpatient cases using the same 30-day incidence rule, and rates of SSTIs occurring during deployments were calculated using deployed person time.

Because SSTI can progress in clinical severity, case-defining diagnoses from hospitalization records were prioritized over those from outpatient records in characterizing incident cases. Thus, if a service member had two or more case-defining encounters for SSTI that occurred within 30 days of each other, an inpatient diagnosis was prioritized over an outpatient diagnosis. In addition, case-defining diagnoses were prioritized by their presumed severity as follows: cellulitis/abscess, erysipelas, carbuncle/furuncle, and "other" (e.g., folliculitis, impetigo, pyoderma, pyogenic granuloma).

The burden of SSTIs including numbers of individuals affected, total numbers of medical encounters, and hospital bed days, was assessed by quantifying the number of inpatient or outpatient medical encounters between 2016 and 2019 with a diagnosis of SSTI in the primary diagnostic position; 2020 was omitted because data were not complete for the entire calendar year at the time of analysis. Medical evacuations for SSTI were assessed by identifying cases that were diagnosed from 5 days prior to 10 days after reported dates of medical evacuations from within to outside of the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM). Recruit/trainees were defined as such by identifying cases during the relevant basic training periods (e.g., 8 weeks for Navy basic training) at service-specific training locations.

Results

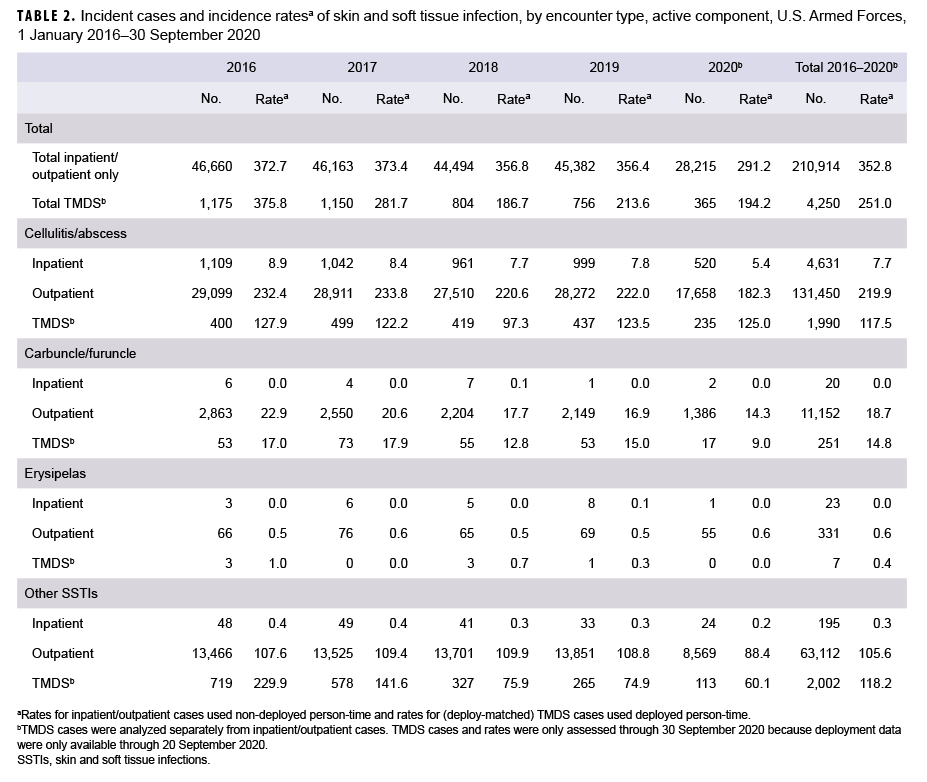

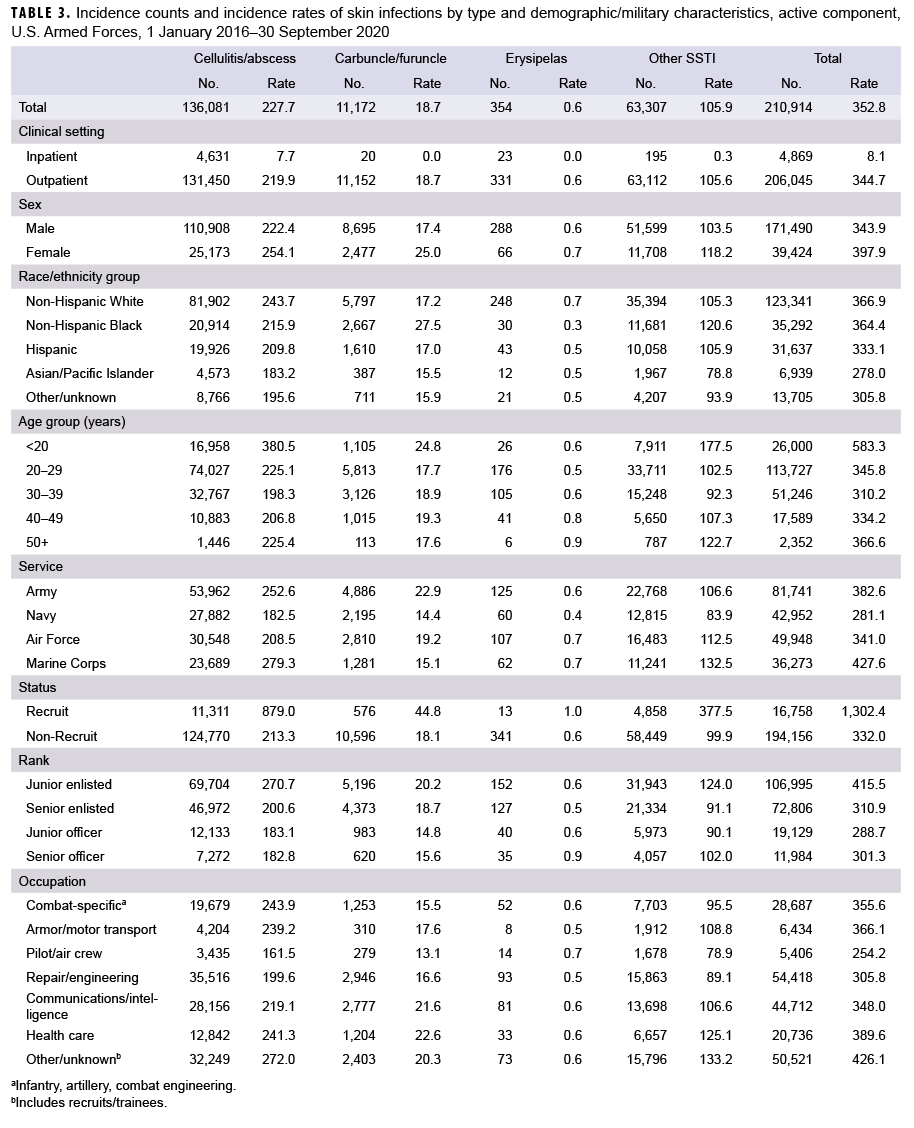

During 1 Jan. 2016 to 30 Sept. 2020, there were 210,914 incident cases of SSTI among active component U.S. military members, corresponding to a crude overall incidence of 352.8 cases per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs) (Table 2). Crude annual incidence rates ranged from 291.2 in the first 3 quarters of 2020 to 373.4 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2017. There was a 21.9% decline in the annual rates of SSTI over the surveillance period. The vast majority of total cases (97.7%) were treated in outpatient facilities (overall rate: 344.7 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Table 3). By contrast, the crude overall SSTI rate in inpatient facilities was 8.1 per 10,000 p-yrs.

Of all incident diagnoses, 30.0% were classified as "other SSTI" (e.g., folliculitis, impetigo, pyoderma); 64.5% were cellulitis/abscess; 5.3% were carbuncles/furuncles; and 0.2% were erysipelas (Table 3, data not shown). Among hospitalized cases, cellulitis/abscess was the most frequent diagnosis (n=4,631; 7.7 per 10,000 p-yrs).

For all SSTIs, overall incidence rates were higher among females than males (Table 3). Compared to Hispanic, Asian/Pacific Islander, and those of other/unknown race/ethnicities, non-Hispanic Black service members had higher rates of carbuncles furuncles and "other SSTI". In contrast, non-Hispanic White service members had higher rates of cellulitis/abscess and erysipelas. Overall rates of cellulitis/abscess, carbuncles furuncles, and "other SSTIs" were highest among service members in the youngest (<20 years) age group. Across the services, rates of cellulitis/abscess were highest among Marine Corps and Army members.

Overall rates of carbuncles/furuncles were higher among Army members; rates of erysipelas were slightly higher among Air Force and Marine Corps members; and rates of "other SSTIs" were highest among Marine Corps members (Table 3).

For all SSTIs, overall rates were higher among recruits compared to non-recruits. Rates of cellulitis/abscess, carbuncle/furuncle, and "other SSTIs" were higher in the junior enlisted ranks compared to officers and senior enlisted. The rate of cellulitis/abscess was highest among service members in "other/unknown" occupations (including recruits/trainees), as compared with those in combat-specific, armor/motor transport, pilot/air crew, repair/engineering, communications/intelligence, or health care occupations. The rate of carbuncles/furuncles was slightly higher among those in health care occupations. Overall rates of "other SSTIs" were highest among those in "other/unknown" and health care occupations, respectively (Table 3).

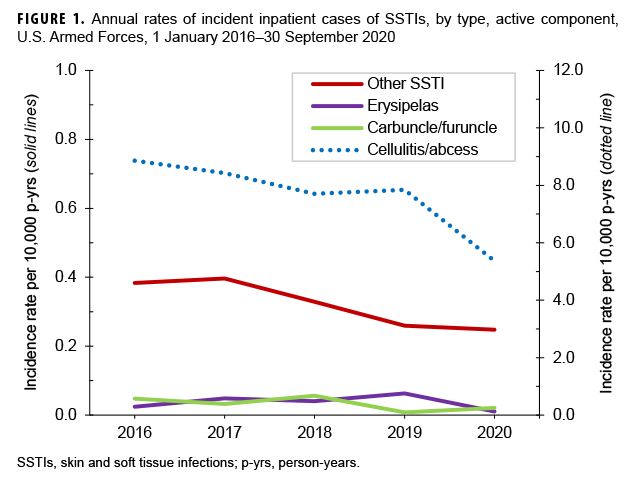

Overall and by year, cellulitis/abscess was the most frequent diagnosis for SSTI associated hospitalizations (Table 2). However, annual rates of cellulitis/abscess associated hospitalizations decreased from 2016 (8.9 per 10,000 p-yrs) to the first 3 quarters of 2020 (5.4 per 10,000 p-yrs). During the surveillance period, hospitalization rates for "other SSTIs" also decreased from 0.4 to 0.2 per 10,000 p-yrs (Table 2, Figure 1). Hospitalization rates for all other skin infection types remained relatively low and stable throughout the period.

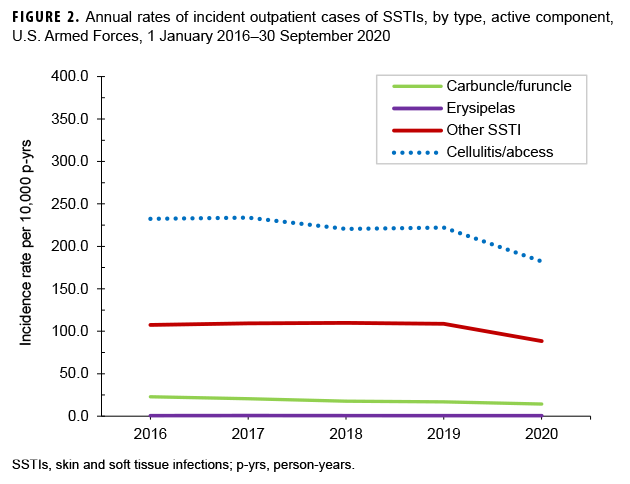

Overall and by year, cellulitis/abscess was the most frequent classification among infections treated in outpatient settings (Table 2, Figure 2). Crude annual rates of outpatient diagnoses of "other SSTIs" carbuncles/furuncles, and cellulitis/abscess decreased during the surveillance period (% change in annual rates from 2016 through 2020: 17.8%, 37.4%, and 21.6%, respectively). Crude annual rates of outpatient treated erysipelas were low and stable throughout the surveillance period.

Body site

Of the incident cases of cellulitis/abscess, the lower extremity was most frequently affected (33.6% of cases; n=45,732) body site, followed by the upper extremity (28.3%; n=38,449), the trunk (14.2%; n=19,368), other/unspecified region (12.4%; n=16,846), and the head/face/neck (11.5%; n=15,686) (data not shown). Cases affecting the upper extremity were more commonly in the arm (16.4%; n=22,259) and finger (11.1%; n=15,042), followed by the hand (0.8%; n=1,148). Cellulitis/abscess cases affecting the lower extremity were more commonly in the leg (22.6%; n=30,814) and toe (10.3%; n=14,056), followed by the foot (0.6%; n=862). A total of 6,892 cases (5.1%) occurred in the buttock. In addition, 10,800 cases (7.9%) were in the face, 2,996 (2.2%) were in the neck, and 1,890 (1.4%) were in the head or scalp.

Of the incident cases of carbuncle/furuncle, the trunk was the most frequently affected region (28.0% of cases; n=3,130), followed by other/unspecified regions (23.1%; n=2,586), the head/face/neck (22.5%; n=2,516), upper extremity (15.1%; n=1,692), and lower extremity (11.2%; n=1,248) (data not shown). Cases in the upper extremity were more commonly in the arm (14.2%; n=1,584), and cases in the lower extremity were more commonly in the leg (10.4%; n=1,160). A total of 1,217 cases (10.9%) occurred on the face, 877 on the buttock (7.8%), 687 on the neck (6.1%), and 612 (5.5%) on the head or scalp.

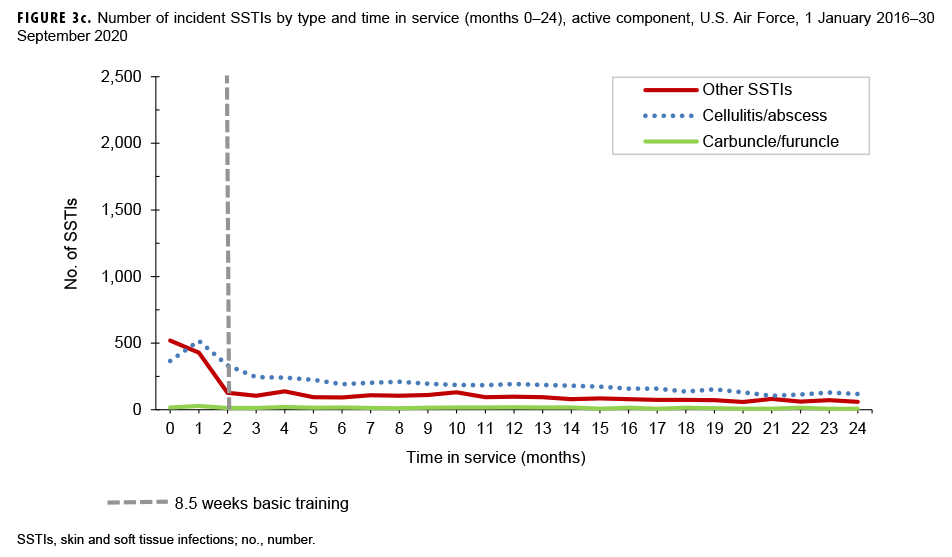

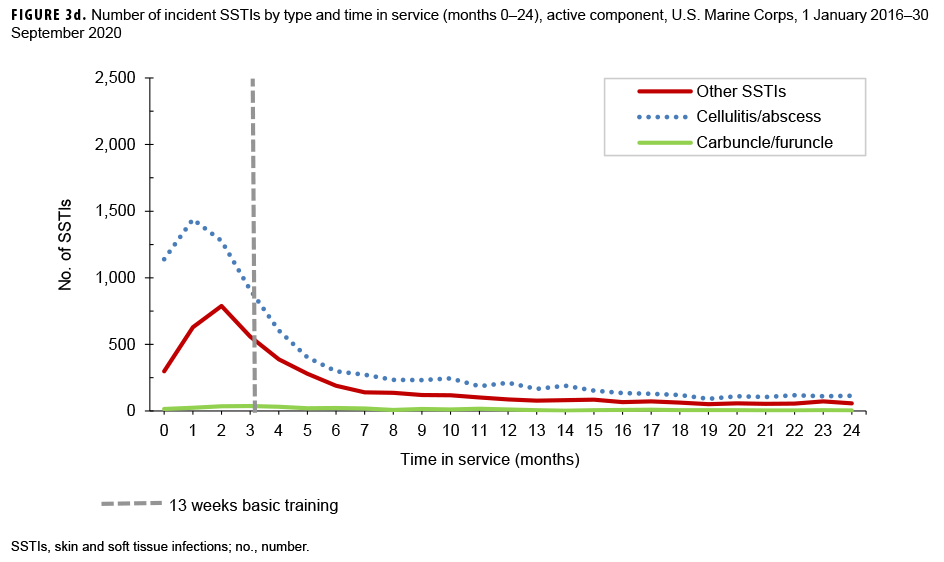

Time in service

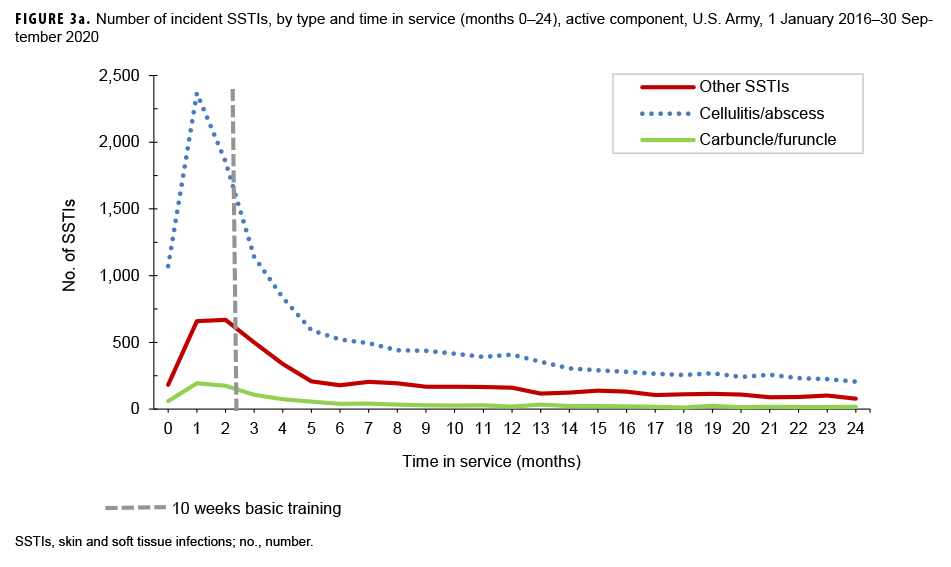

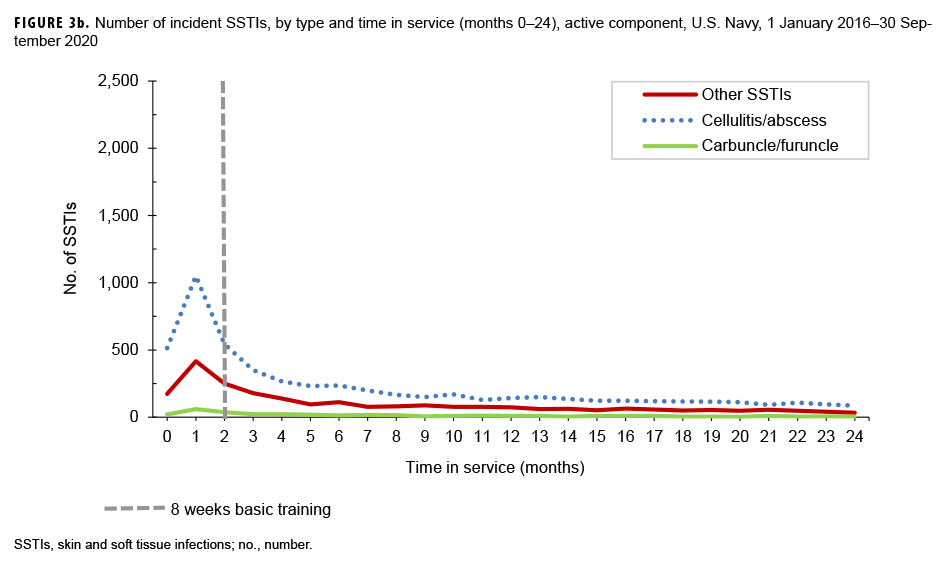

Among individuals who entered military service during the surveillance period, peaks of SSTI-related medical encounters occurred during the first 3 months of military service; typically, this is the period of initial military training, and military trainees are known to be at increased risk of SSTI. In all service branches, cellulitis/abscess was the most frequently diagnosed type of skin infection during this early period of service (Figures 3a–d).

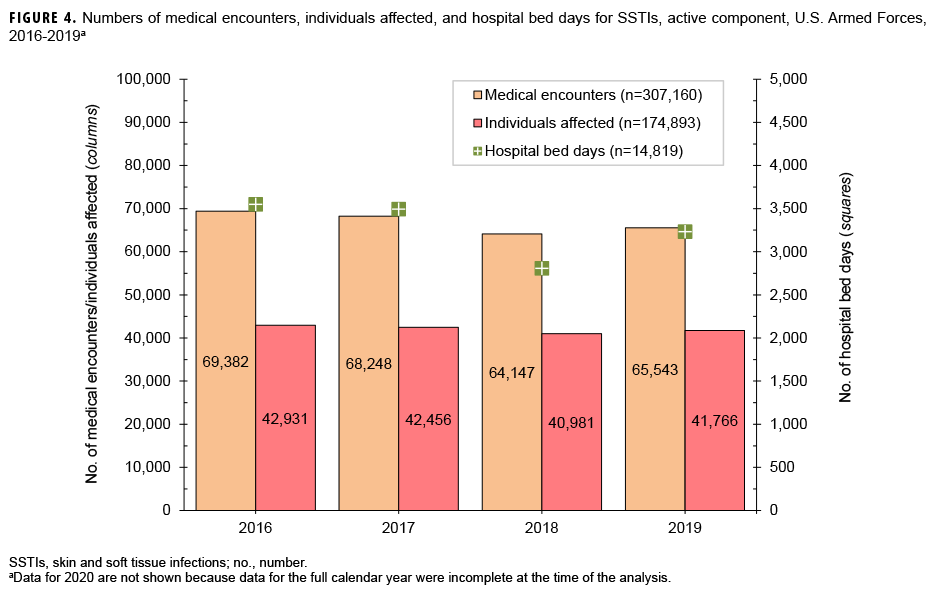

Burden of disease

During the surveillance period, 174,893 service members were treated for SSTI; the infections accounted for 307,160 medical encounters and 14,819 hospital bed days (Figure 4). Annual numbers of medical encounters and individuals affected decreased 5.5% and 2.7%, respectively, from 2016 through 2019, which was the last complete calendar year of data at the time of the analysis.

Annual numbers of bed days decreased 8.9% between 2016 and 2019 (Figure 4). Cellulitis/abscess accounted for more than two-thirds (69.1%) of all SSTI-associated medical encounters, 68.2% of individuals affected, and 95.8% of hospital bed days (Figure 4, data not shown).

SSTI during deployment

From 1 Jan. 2016 through 30 Sept. 2020, there were 4,250 incident cases of SSTI in theaters of operation, corresponding to an overall incidence of 251.0 per 10,000 p-yrs (Table 2). "Other SSTIs" (47.1%) and cellulitis/abscess (46.8%) were the most frequent classifications. Frequencies of carbuncles/furuncles (5.9%) and erysipelas (0.2%) were low. During the surveillance period, crude overall rates of SSTI during deployment markedly decreased, from 375.8 to 194.2 per 10,000 p-yrs (33.2% decrease) (Table 2). The majority of SSTIs diagnosed in theater occurred while deployed to Kuwait (25.2%; n=1,069), Qatar (21.1%; n=895), United Arab Emirates (8.6%; n=366), Jordan (7.3%; n=309), or Afghanistan (7.2%; n=305). Lastly, there were 9 SSTI-associated medical evacuations from theater. Of these, 8 were classified as cellulitis/abscess and 1 was an unspecified local infection of the skin and subcutaneous tissue (data not shown).

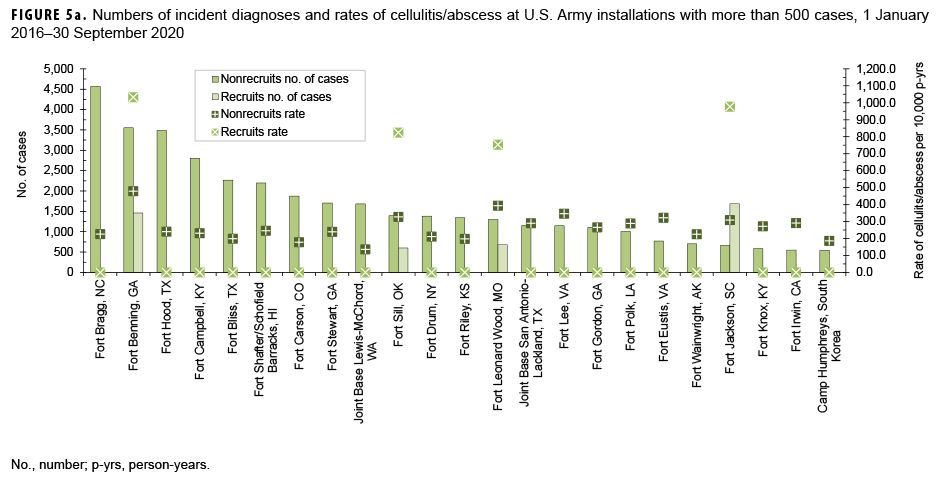

Rates of cellulitis/abscess by service, installation, and recruit status

Among Army basic training sites, overall incidence rates of cellulitis/abscess in the recruit population were highest at Fort Benning, GA (1,032.6 per 10,000 p-yrs), Fort Jackson, SC (976.5 per 10,000 p-yrs), Fort Sill, OK (824.4 per 10,000 p-yrs), and Fort Leonard Wood, MO (752.9 per 10,000 p-yrs), respectively (Figure 5a). Among nonrecruits, limited to Army installations where more than 500 cases of cellulitis/ abscess were diagnosed, overall rates were highest at Fort Benning, GA (479.1 per 10,000 p-yrs) and Fort Leonard Wood, MO (393.0 per 10,000 p-yrs).

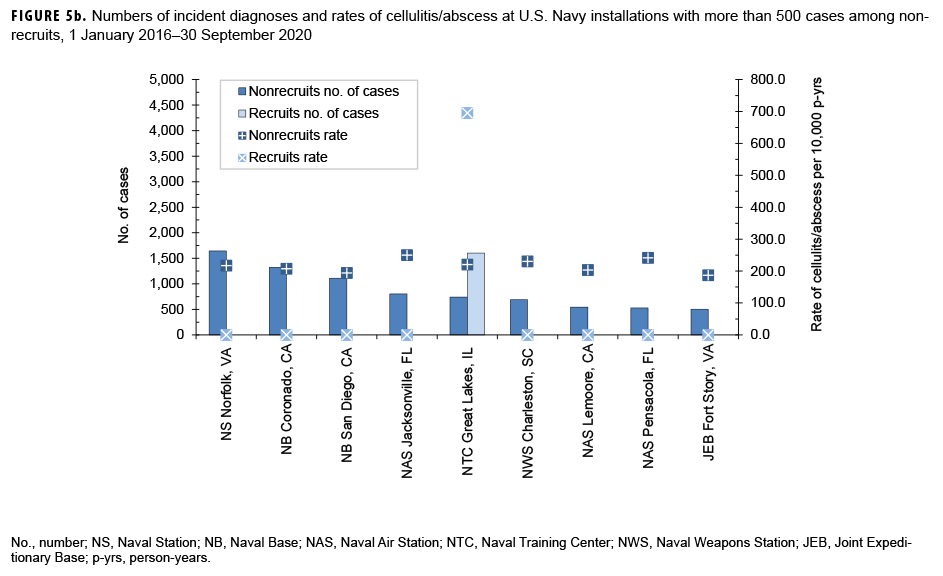

The overall incidence rate of cellulitis/abscess in the Navy recruit population at Naval Station Great Lakes, IL was 695.1 per 10,000 p-yrs (Figure 5b). Among nonrecruits at Navy installations where more than 500 cases of cellulitis/abscess were diagnosed, overall rates were highest at Naval Air Station (NAS) Jacksonville, FL (250.1 per 10,000 p-yrs), NAS Pensacola, FL (241.3 per 10,000 p-yrs), and Naval Weapons Station Charleston, SC (230.0 per 10,000 p-yrs).

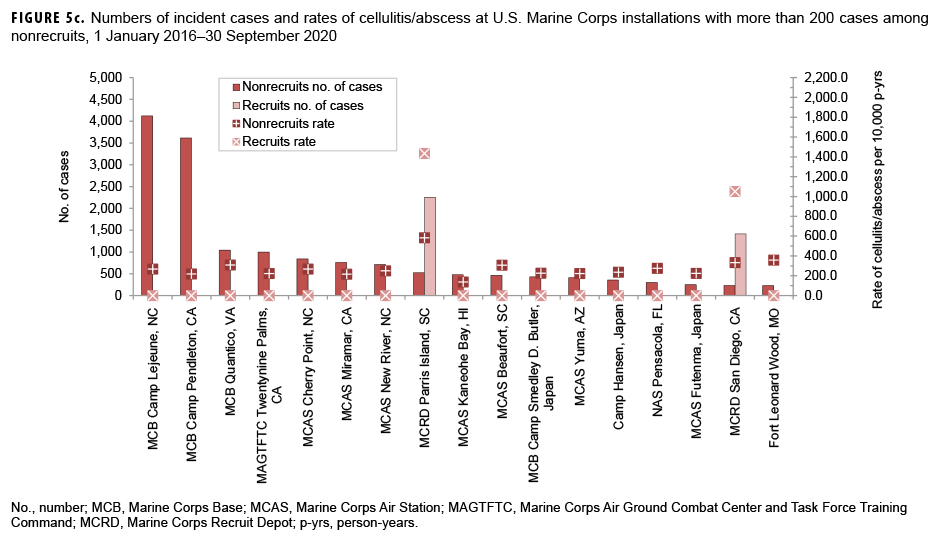

Among Marine Corps training centers, overall cellulitis/abscess rates in the recruit population were highest at MCRD Parris Island, (1,435.1 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Figure 5c), followed by MCRD San Diego (1,049.6 per 10,000 p-yrs). Among nonrecruits at Marine Corps installations where more than 200 cases were diagnosed, the rate was highest at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, SC (583.9 per 10,000 p-yrs).

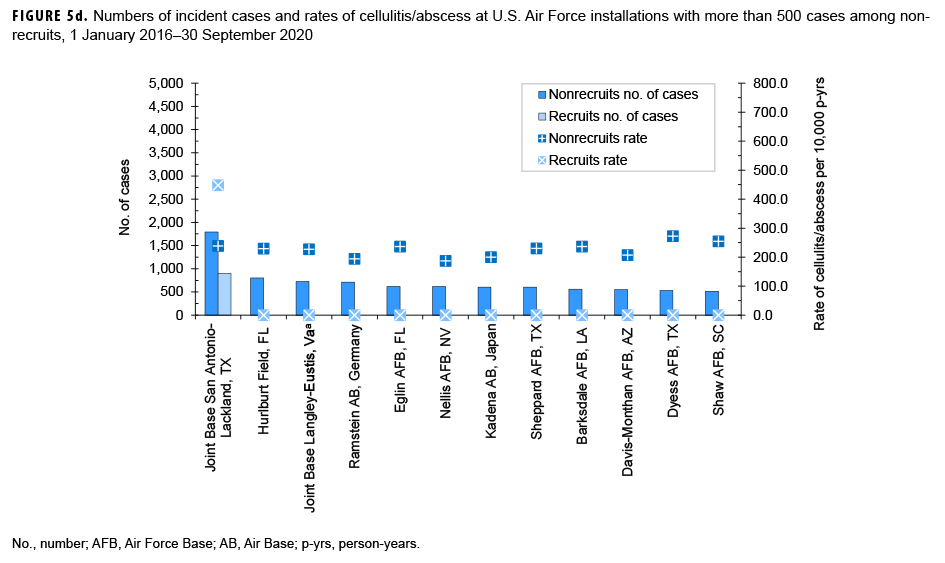

The overall cellulitis/abscess rate in the Air Force recruit population at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, TX was 447.8 per 10,000 p-yrs (Figure 5d). Among nonrecruits at Air Force installations where more than 500 cases were diagnosed, rates were highest at Dyess Air Force Base (AFB), TX (272.2 per 10,000 p-yrs), Shaw AFB, SC (254.4 per 10,000 p-yrs), and Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland, TX (239.0 per 10,000 p-yrs).

Editorial Comment

This report found that the burden of SSTI in military populations remains high, with an overall rate of 352.8 per 10,000 p-yrs between 1 Jan. 2016 and 30 Sept. 2020. Although contemporaneous rates of SSTI in U.S. civilian populations have not been reported, it is known that certain military personnel are at disproportionately higher risk for SSTI when compared to their nonmilitary counterparts. These rate differences are likely due to the frequent engagement of military personnel in training-and deployment-related exercises and operations where an increased frequency of minor traumatic injuries to skin (e.g., abrasions, cuts, and scrapes) which, when compounded by limited access to good hygiene, increases their susceptibility to microbial contamination and subsequent infection.

The current analysis demonstrates that SSTI rates in the military are highest among new recruits/trainees and among those in a deployed setting.3,10 Across all services, overall SSTI rates in recruit/trainee populations were 1.8–2.7 times higher than that of nonrecruit/nontrainee populations at the same installation. Physical conditions of military training and operational environments (i.e., crowding, infrequent hand washing/bathing, and environmental contamination) favor the transmission of microbial pathogens and thereby increase infection risk in these settings,2 suggesting that medical countermeasures for SSTI would be most cost effective when specifically targeted to these high risk populations.

Among all initial military trainees, overall rates of cellulitis/abscess were highest among Marine Corps members. The reasons for these service-specific differences in SSTI rates have not been explored to date and might be attributable to differences in the type, intensity, and/or duration of initial military training, each of which may affect a given recruit/trainee's risk of infection. Outbreaks of SSTI among initial military trainees have been reported in California, Texas, and Georgia.1-3 Further evaluation of epidemiologic characteristics (e.g., specific training activities associated with increased SSTI risk), personal/environmental hygiene practices, and potential environmental reservoirs for SSTI-associated pathogens is warranted.

Annual incidence rates declined by 21.9% over the surveillance period. Moreover, the overall incidence of 352.8 per 10,000 p-yrs from 2016–2020 represents a 37% decline in incidence from the 2013– 2016 surveillance period.10 A decline or plateau in rates of SSTIs in ambulatory, emergency department, and inpatient settings has been reported from nonmilitary health care facilities in the U.S.7-9 The reasons for the observed decrease or stabilization of SSTI rates in the U.S. civilian sector are unknown.

Limitations to this study include the use of ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes to identify skin and soft tissue infections, which depend on accurate coding in the patient record and may result in misclassification of the outcome. ICD-9 codes were included because, at the time of analysis, some TMDS records still included these codes. In addition, recruits were identified using an algorithm based on age, rank, location, and time in service. This method is only an approximation and likely resulted in some misclassification of recruit training status. Further, the COVID-19 pandemic impacted training cycles in several services in 2020 (e.g., the training cycle length for Air Force recruits was shortened to 7.5 weeks and Keesler AFB served as an alternate recruit training location). Such changes were not incorporated into the recruit-finding algorithm at the time of the analysis.

Early diagnosis and treatment of SSTI—particularly in high-risk settings such as initial military training and deployment settings—is critical to decreasing the significant health care burden and cost that these infections impose on the MHS. Personal hygiene-based strategies failed to prevent SSTIs in a U.S. Army trainee population11 and vaccines for the leading causes of SSTI do not exist. Research, education, and training activities focused on SSTI control and prevention among high-risk military personnel should be high priorities. Specific recommendations to prevent, evaluate, diagnose, and treat methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infections in U.S. military populations are summarized at https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC Resource Library/CA-MRSA_FS_13-021-0914.pdf

Author affiliations: Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Stahlman, Ms. Williams, Mr. Oh); Infectious Disease Clinical Research Program, Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Drs. Millar and Tribble); Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Bethesda, MD (Dr. Millar).

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Henry M. Jackson Foundation for the Advancement of Military Medicine, Inc., Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

- Campbell KM, Vaughn AF, Russell KL, et al. Risk factors for community-associated methicillinresistant Staphylococcus aureus infections in an outbreak of disease among military trainees in San Diego, California, in 2002. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4050–4053.

- Millar EV, Rice GK, Elassal EM, et al. Genomic Characterization of USA300 Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) to Evaluate Intraclass Transmission and Recurrence of Skin and Soft Tissue Infection (SSTI) Among High-Risk Military Trainees. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:461–468.

- Webber BJ, Federinko SP, Tchandja JN, Cropper TL, Keller PL. Staphylococcus aureus and other skin and soft tissue infections among basic military trainees, Lackland Air Force Base, Texas, 2008– 2012. MSMR 2013;20:12–15; discussion 5-6.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Bacterial skin infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2012. MSMR. 2013;20:2–7.

- Landrum ML, Neumann C, Cook C, et al. Epidemiology of Staphylococcus aureus blood and skin and soft tissue infections in the US military health system, 2005–2010. JAMA. 2012;308:50–59.

- Ray GT, Suaya JA, Baxter R. Incidence, microbiology, and patient characteristics of skin and soft-tissue infections in a U.S. population: a retrospective population-based study. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:252.

- Klein EY, Mojica N, Jiang W, et al. Trends in Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Hospitalizations in the United States, 2010-2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:1921–1923.

- Morgan E, Hohmann S, Ridgway JP, Daum RS, David MZ. Decreasing Incidence of Skin and Softtissue Infections in 86 US Emergency Departments, 2009–2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2019;68:453–459.

- Fritz SA, Shapiro DJ, Hersh AL. National Trends in Incidence of Purulent Skin and Soft Tissue Infections in Patients Presenting to Ambulatory and Emergency Department Settings, 2000–2015. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;70:2715–2718.

- Stahlman S, Williams VF, Oh GT, Millar EV, Bennett JW. Skin and soft tissue infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2013–2016. MSMR. 2017;24:2–11.

- Ellis MW, Schlett CD, Millar EV, et al. Hygiene strategies to prevent methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus skin and soft tissue infections: a cluster-randomized controlled trial among high-risk military trainees. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58:1540–1548.