Background

SARS CoV-2 and the illness it causes, COVID-19, have exacted a heavy toll on the global community. Most of the identified disease has been in the elderly and adults. In April 2020, a rare hyperinflammatory syndrome called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) was reported in Europe in a number of children with SARS-CoV2 infections. The cluster was initially characterized as cases with symptoms compatible with Kawasaki's disease.1 Cases presented with symptoms including systemic hyperinflammation, persistent fever, and multisystem organ dysfunction. In the U.S., cases of MIS-C have been disproportionately reported among Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black children 6 to 12 years old who presented with severe symptoms.2 According to the Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC), as of 3 May 2021, 3,742 cases of MIS-C were reported in the U.S., including 35 deaths.3

In an effort to detect potential cases of MIS-C in the Military Health System (MHS), the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD) used the Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-based Epidemics (ESSENCE), a syndromic surveillance system which uses outpatient data to monitor trends and increases in health care encounters that may represent changes in the incidence of disease. Users of ESSENCE employ the system to analyze MHS clinical data sources in near real-time, including diagnosis codes, free text chief complaint or reason-for-visit data fields, reportable medical events (RME), laboratory and radiology data, and prescription drug information to develop a picture of disease syndromes based on health care encounters.4,5 The goal of this analysis was to ascertain if user-built ESSENCE queries applied to records of outpatient MHS health care encounters are capable of detecting MIS-C cases that have not been identified or reported by local public health departments.

Methods

The AFHSD used ESSENCE to create a query based on the case definition of MIS-C developed by the CDC to identify potential MIS-C cases. The query included MIS-C-related International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes and free text chief complaint and reason-for-visit data fields from records of outpatient medical encounters for health care beneficiaries of the MHS 20 years old or younger who sought care between Oct. 19, 2020 and March 12, 2021. The query was adapted from the CDC-developed syndromic surveillance query, but the AFHSD query was modified to exclude those codes which are not present in AFHSD ESSENCE (Z86.16 [personal history of COVID-19] and Z20.822 [exposure to COVID-19 or SARS-CoV-2 infection]). The AFHSD-developed query selected ICD-10 codes in any diagnostic position in the electronic medical record for any outpatient encounter during the study period. Chief complaints were retrieved from patients' "reason for visit" free text field for each health encounter. The search criteria for ESSENCE's free text queries are built around Boolean logical operators and regular expressions which allow for a high level of customization.6

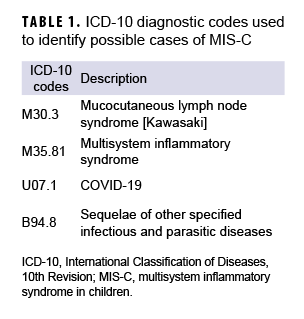

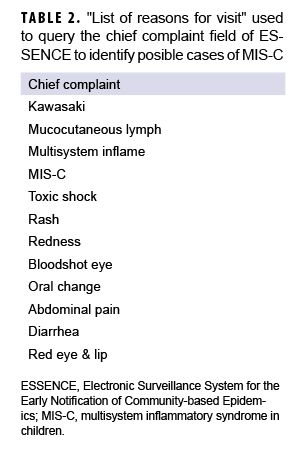

Four ICD-10 codes and 12 chief complaints (Tables 1, 2) were used to create the automated ESSENCE MIS-C query for searching records of all outpatient health encounters at nearly 400 military treatment facilities (MTFs) in real-time. Demographic and military variables, including age (in years), sex, race/ethnicity, ICD-10 codes, patient identifiers, and location were extracted for analysis. All Click to closeDirect CareDirect care refers to military hospitals and clinics, also known as “military treatment facilities” and “MTFs.”direct care outpatient encounters with 1 or more of the ICD-10 codes or chief complaints of interest were selected to create a list of potential cases. Data details were downloaded on a weekly basis, verified, and coded as confirmed MIS-C cases by registrars trained in infectious disease manual data abstraction associated with the Department of Defense (DoD) COVID-19 registry.

The CDC case definition was used to confirm MIS-C cases. This definition includes an individual under 21 years old presenting with fever (>100.4 °F/38.0 °C) or report of subjective fever lasting 24 hours or longer), laboratory evidence of inflammation and a positive test for SARS-CoV-2 infection by RT-PCR, serology, or antigen test or COVID-19 exposure within the 4 weeks prior to the onset of symptoms in the clinical setting of severe inflammatory illness without other identifiable etiology.3

Results

During the surveillance period, the AFHSD MIS-C ESSENCE query identified 60 encounters that met selection criteria. The month of February 2021 had the most MIS-C-related encounters with 15 (25%) occurring during this time (data not shown). Out of 60 possible cases, 40 (66%) were males and 36 (60%) were 0–8 years olds (mean=8.5 years) (data not shown). Half of the MIS-C-related encounters (n=30) were in the southeast region of the U.S., and 9 (15%) were in overseas military clinics (data not shown). The most common ICD-10 code recorded was "M30.3-Mucocutaneous lymph node syndrome (Kawasaki)." Of the 60 records identified as possible cases by ESSENCE, 10 cases of MIS-C were confirmed by the DoD COVID-19 health records review process (17%). Four (40%) of the 10 confirmed cases were male and 4 were female (40%). Information on sex was not available for 2 of the confirmed cases. Half of the confirmed cases were 7–10 years old (mean=12 years; range=7–18 years).

Editorial Comment

Monitoring disease progression of the COVID-19 pandemic for situational awareness has been the current focus of the syndromic surveillance. The emergence of MIS-C reported in military beneficiaries should widen the focus on how to monitor disease progression in diverse populations. Although MIS-C is a rare condition among children who have developed COVID-19, it is still of great concern to public health officials in the military health care system.4 The ability to detect individual cases of disease was not originally how syndromic surveillance was designed to function. The main objective of syndromic surveillance is to detect a cluster or outbreak of disease before diagnosis.

There are some limitations to using ESSENCE to detect MIS-C encounters. A proportion of ESSENCE records that were received were deidentified; these records were not used in the analysis. In addition, records of Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care encounters were not included in the analysis. Given these limitations, the findings of this analysis should not be construed as a complete representation of MIS-C cases in the surveyed population. Moreover, because the use of ESSENCE was limited to outpatient clinic data, the current analysis did not include the more severe cases seen in emergency departments and urgent care centers which are visible through the civilian form of ESSENCE.

The purpose of the analysis was to create a query that could identify possible outpatient cases of MIS-C. The MIS-C query was able to capture 10 cases of the rare condition of MIS-C during the surveillance period while minimizing the number of encounters (n=60) which met the selection criteria out of millions of encounters. ESSENCE has shown the ability to detect potential cases of MIS-C through health encounters at MTFs across the MHS. This capability will expand the biosurveillance efforts of AFHSD in response to future emerging infectious diseases and other threats of military interest. Furthermore, civilian surveillance systems may use this or similar queries to identify previously unreported cases of MIS-C in the civilian population.

Author affiliations: Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (Dr. Russell and Col. Vick).

References

1. Riphagen S, Gomez X, Gonzalez-Martinez C, et al. Hyperinflammatory shock in children during COVID-19 Pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395(10237):1607–1608.

2. Feldstein LR, Tenforde MW, Friedman KG, et al. Characteristics and outcomes of US children and adolescents with multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) compared with severe acute COVID-19. JAMA. 2021;325(11):1074–1087.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Health Department-Reported Cases of Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) in the United States. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 11 May 2021. Accessed 1 June 2021. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#mis-national-surveillance

4. Burkom H, Loschen W, Wojcik R, et al. Electronic Surveillance System for the Early Notification of Community-Based Epidemics (ESSENCE): Overview, Components, and Public Health Applications. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(6):e26303.

5. Scholl L, Liu S, Vivolo-Kantor A, et al. Development and Validation of a Syndrome Definition to Identify Suspected Nonfatal Heroin-Involved Overdoses Treated in Emergency Departments. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2021;27(4):369–378.

6. Stein Z. National Syndromic Surveillance Program (NSSP). Free-text coding in NSSP-ESSENCE: Part 1. Accessed 1 December 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nssp/tech-tips/free-text-coding/part1.html

7. Centers for Disease Control and prevention. Emergency Preparedness and Response. Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children (MIS-C) Associated with Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19). Accessed 1 December 2021. https://emergency.cdc.gov/han/2020/han00432.asp