Abstract

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) individuals are at a particularly high risk for suicidal behavior in the general population of the United States. This study aims to determine if there are differences in the frequency of lifetime suicide ideation and suicide attempts between heterosexual, lesbian/gay, and bisexual service members in the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces. Self-reported data from the 2015 Department of Defense Health-Related Behaviors Survey were used in the analysis. Multivariable logistic regression demonstrated that lesbian/gay and bisexual service members were more likely to report past suicide ideation when compared to heterosexual service members (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] for lesbian/gay: 1.79; 95% CI: 1.14-2.82; AOR for bisexual: 2.33; 95% CI: 1.56-3.49). Similar results were observed for past suicide attempt for lesbian/gay (AOR: 2.29; 95% CI: 1.15-4.57) and bisexual SMs (AOR: 2.04; 95% CI: 1.24-3.38). Despite disparities in suicide ideation and attempt by sexual orientation, a majority of service members’ behavioral health questionnaires do not assess sexual orientation. Clinical screenings of suicide risk in military settings should factor in sexual orientation to more comprehensively assess association between sexual orientation and suicidal behavior in this population.

What are the new findings?

This study found that lesbian/gay and bisexual service members had a 1.8 and 2.3-fold higher odds, respectively, of suicide ideation compared to heterosexual SMs. Furthermore, lesbian/gay and bisexual SMs had a 2.3 and 2.0-fold higher odds, respectively, of suicide attempt compared to heterosexual SMs.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Increased odds of suicide ideation and attempt among gay, lesbian, and bisexual service members indicate important disparities in mental health which may be associated with decreased readiness. Information about sexual orientation should be collected more routinely in order to determine if there are other mental and physical health disparities within this population.

Background

The age-adjusted suicide rate in the U.S. increased 24% between 1999 and 2014.1 Suicide is now the tenth leading cause of death in the US, with 47,173 cases reported in 2017.2 Although suicide has steadily increased among the US general population, particular demographic groups are at a higher risk for suicidal ideation, attempt, and death by suicide.3

Lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) populations suffer a disproportionate risk of suicidal behavior when compared to the US general population.4,5 In a study of 123,289 suicide decedents reported to the US National Violent Death Reporting System, Lyons et al. reported that gay male decedents were more likely than non-gay male decedents to have had a documented mental health problem, depression at the time of death, recent treatment for mental health or substance abuse problems, a history of suicidal thoughts or plans, and/or relationship problems.6 Similar risk factors were observed when comparing lesbian decedents and non-lesbian decedents.6

In a study using data from the 2015–2016 Canadian Community Health Survey, LGB respondents were more likely to report suicide ideation across the lifespan.7 A 2008 systematic review and meta-analysis of the prevalence of mental health disorders, substance misuse, suicide ideation, and suicide attempt reported that LGB individuals had an approximately 2.5-fold higher risk of lifetime suicide attempt when compared to heterosexual populations.8 Numerous other studies among LGB youth and young adults have revealed similar disparities.9-13

Within LGB populations, those in certain occupations may be at an even higher risk of suicidal behavior. In 1994, the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy was implemented which allowed LGB persons to serve in the military but prohibited LGB service members (SMs) from disclosing their sexuality. The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy was removed in 2011, but the effects of the policy had negative mental health ramifications for LGB SMs, including suicide ideation and attempt.14-16

Adverse mental health outcomes are also reflected in LGB veteran populations. Analysis of the 2005–2010 Massachusetts Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey found that 11.5% of LGB veterans reported suicidal ideation in the past year, compared with only 3.5% of heterosexual veterans.17 Among veterans presenting for military sexual trauma (MST) consultation and treatment, Sexton and colleagues reported that 54% of LGB veterans reported a history of suicide attempt, compared with only 28% of non-LGB veterans.18 A study using Veterans Health Administration electronic health records reported that suicide was the fifth leading cause of death for LGB veterans from October 2000 to September 2017, but only the tenth leading cause of death in the general population during this time frame.19

Despite evidence of elevated risk of suicide ideation and attempt among LGB veterans, there is a paucity of other studies examining suicidal behavior among active component military LGB populations.20 At the time of this analysis, only 1 study had compared LGB service members’ suicide behavior to that of heterosexual service members. While this study found an increased odds of suicide attempt among LGB SMs, the study did not analyze suicide ideation or control for demographic variables beyond age group.21 As Matarazzo et al. opined, “Being a member of the US military, as well as identifying as [LGB], could potentially constitute a double-edged risk for suicide.” Research on each of the aforementioned predisposing factors for suicidal behavior is essential to maintain military readiness.

The primary objective of this study was to use data from the 2015 Department of Defense (DoD) Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) to determine if there are differences in the likelihood of past suicide ideation and attempts between active component heterosexual, gay or lesbian, and bisexual SMs, controlling for demographic variables.

Methods

Study background

The HRBS is a DoD survey used to understand the health and well-being of service members across all 5 branches of military service.22 The Defense Health Agency contracted with RAND Corporation to develop and administer the 2015 HRBS. Potential participants were eligible for the survey if they were: 1) active component U.S. military service members; 2) serving in the Air Force, Army, Marine Corps, Navy, or Coast Guard; 3) not deployed as of August 31, 2015, and 4) not enrolled as cadets in service academies, senior military colleges, or Reserve Officers’ Training Corps programs.22 Members of the National Guard and Reserve were excluded from the list of potential participants. Potential participants were stratified by service branch, pay grade, and birth sex; service members were randomly sampled from within each stratum. Invited participants were solicited via letter with follow up postcard and email reminders and were provided with a universal resource locator (URL) to complete the survey. All survey responses were anonymous.

The outcomes for this analysis were lifetime suicide ideation and lifetime suicide attempt. Suicide ideation was measured using respondents’ answers to the following question, “In your lifetime, did you ever seriously think about trying to kill yourself?” Suicide attempt was measured using respondents’ answers to the following question: “In your lifetime, have you ever tried to kill yourself?”

Demographic predictors included birth sex, sexual orientation, age group, marital status, educational attainment, and racial/ethnic minority. Sexual orientation was measured with the following question, “Do you consider yourself to be…? Select one response” with three options: Heterosexual or straight; Gay or lesbian; Bisexual. Unlike other demographics questions, sexual orientation was placed near the end of the survey.

Statistical analyses

The HRBS oversamples service members in certain strata to produce estimates representative of the active component population. The oversampling is accounted for in post-stratification weights. Weighted frequencies with 95% confidence intervals were computed using these post-stratification weights.22 Two multivariable logistic regression models were built to assess the association between lifetime suicide ideation and lifetime suicide attempt with selected demographics and sexual orientation disaggregated (lesbian/gay, bisexual, and heterosexual). Two additional multivariable logistic regression models were built to determine the effects of aggregating the last 2 categories of the sexual orientation variable (lesbian/gay and bisexual) on the suicide ideation and attempt outcomes. Only demographic variables were included in this analysis, since assessment of additional behavioral risk factors would introduce temporal ambiguity with respect to whether or not the risk factors preceded or followed lifetime suicidal behavior outcomes. Neither forward selection nor backward elimination were utilized. All analyses were completed using SAS software (i.e., PROC SURVEYFREQ for frequencies and PROC SURVEYLOGISTIC for multivariable models), version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Results

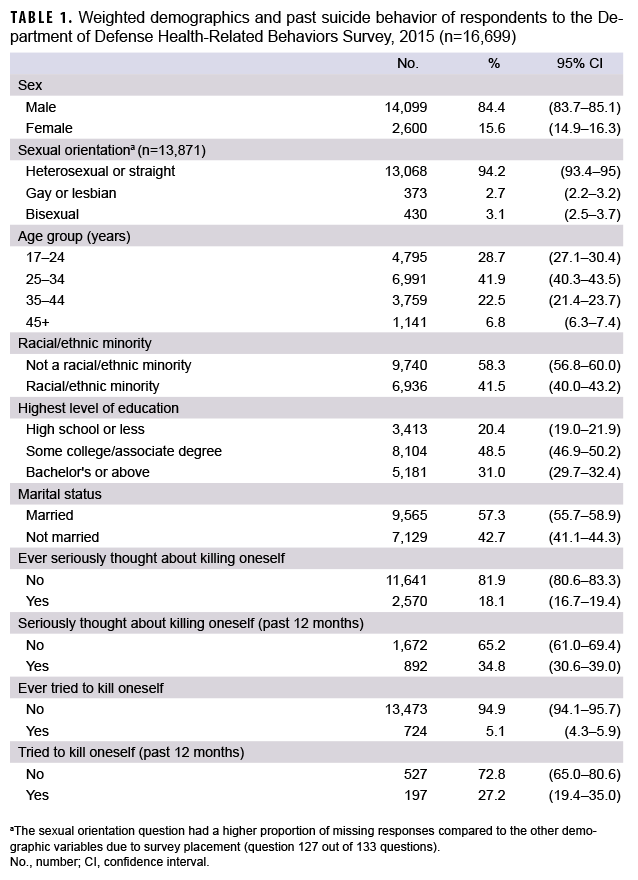

From a total of 195,220 eligible and contactable active component service members, a total of 16,699 usable surveys were obtained (8.6% overall response rate). There were 16,699 total respondents to the 2015 HRBS survey. Of the 13,871 respondents who answered the question on sexual orientation, 94.2% identified as heterosexual, 2.7% identified as gay or lesbian, and 3.1% identified as bisexual (Table 1). In addition, a majority of respondents were between 25 and 44 years of age (64.4%), married (57.3%), had some college education or more (79.5%), and were not a racial or ethnic minority (58.3%).

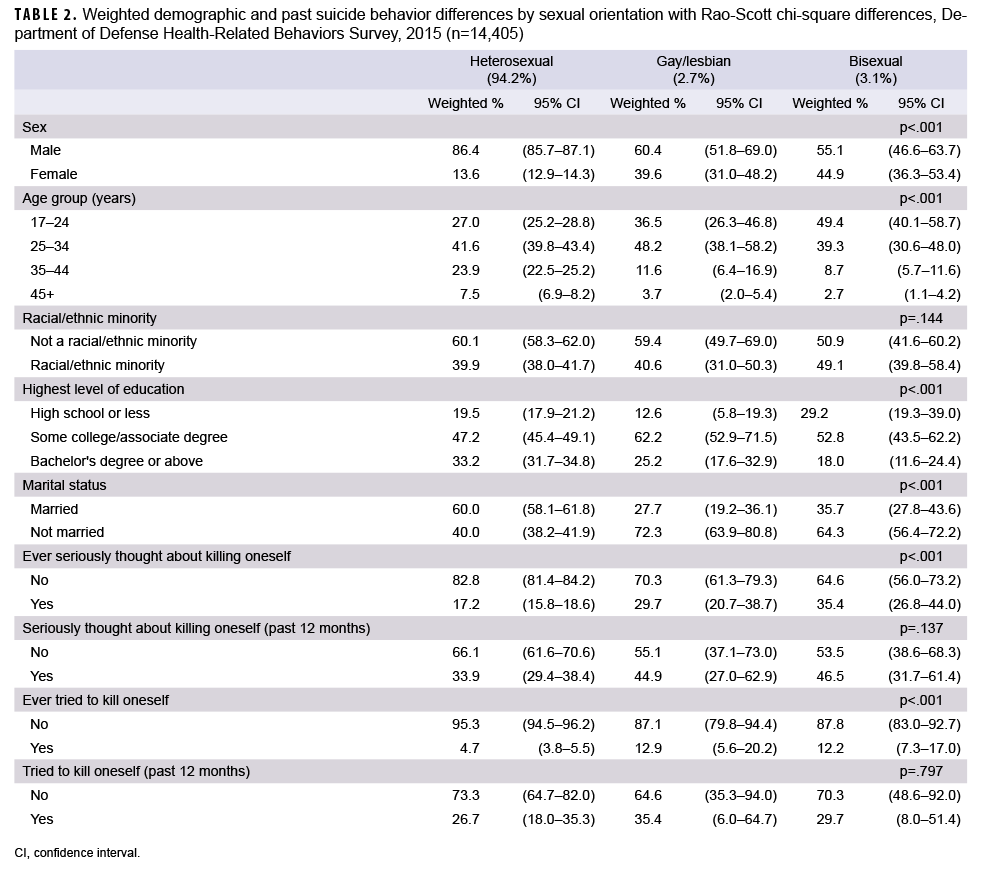

Results of bivariate analyses indicated that 29.7% of lesbian/gay respondents and 35.4% of bisexual respondents reported that they had ever seriously thought about killing themselves, compared to 17.2% of heterosexual respondents (Table 2). Among lesbian/gay respondents, 12.9% responded “yes” to the question, “In your lifetime, have you ever tried to kill yourself?” (Hereafter referred to as suicide attempt), compared to 12.2% of bisexual respondents and 4.7% of heterosexual respondents.

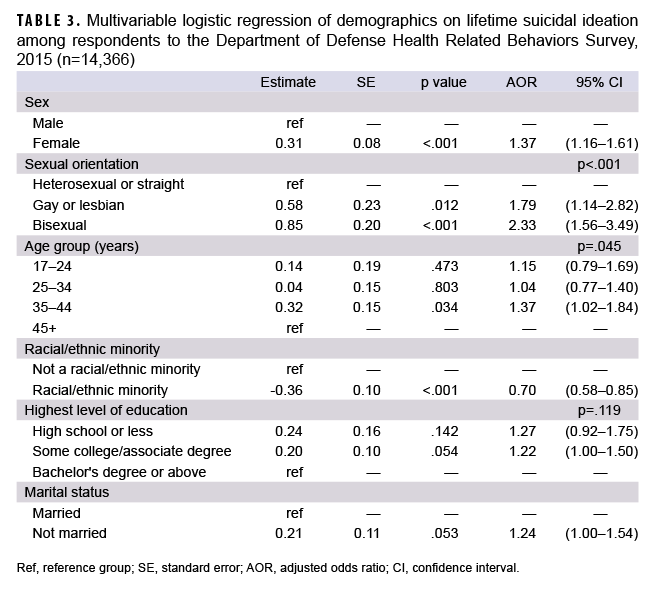

Lesbian/gay and bisexual service members were more likely to report lifetime suicide ideation compared to heterosexual service members (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=1.79; 95% CI: 1.14–2.82 and AOR=2.33; 95% CI: 1.56–3.49, respectively) (Table 3). In addition, compared to their respective counterparts, female service members, and those who were not a racial/ethnic minority (White) were more likely to report lifetime suicide ideation.

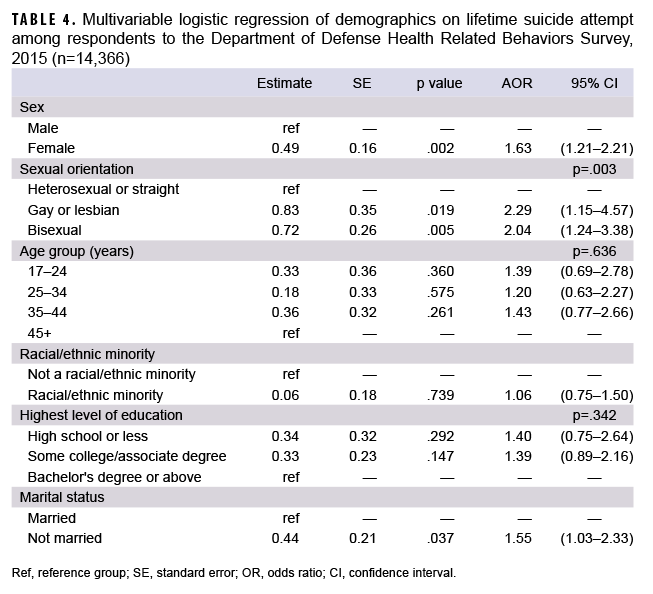

Similar results were observed for past suicide attempt for lesbian/gay service members and bisexual service members compared to heterosexual service members (AOR=2.29; 95% CI: 1.15–4.57 and AOR=2.04; 95% CI: 1.24–3.38, respectively) (Table 4). In addition, compared to their respective counterparts, female service members and those who were not married were more likely to report lifetime suicide attempt.

The last 2 models used the aggregated version of the sexual orientation variable with gay, lesbian, and bisexual SMs collapsed into 1 category. The same patterns held for both lifetime suicide ideation and lifetime suicide attempt. The aggregated groups of lesbians, gay or bisexual service members were more likely to report lifetime suicide ideation and lifetime suicide attempt compared to heterosexual service members (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]=2.07; 95% CI: 1.51-2.83 and AOR=2.16; 95% CI: 1.38–3.38, respectively) (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

The present study found that LGB service members (SMs) had a higher odd of reporting both lifetime suicide ideation and attempt compared to heterosexual SMs. In addition, all models resulted in weighted estimates indicating elevated risk for suicide behavior among female SMs. These suicide behavior trends in an active-component sample largely mirror the disparities reported in civilian samples.13

This study has several limitations. First, although the 2015 HRBS employed a random, stratified sampling design, the response rate was 8.6%.22 Therefore, it is unclear how generalizable these findings are to the entire active component population. However, the overall findings in the 2015 HRBS are similar to the findings in the 2011 HRBS, which had a response rate of 22%.23 Second, 13.7% of respondents had missing data for the sexual orientation question. This degree of item-level missing data (i.e., missingness) may be due to the placement of the sexual orientation question at the end of the survey (question 127 of 133 questions). To determine if the level of missingness on this item was likely due to not reaching the question (survey fatigue) or purposefully omitting a response (social desirability bias), the proportion of missing data on the sexual orientation item was compared to the missingness on a sleep measure which appeared even later in the survey (question 129).

The sleep and sexual orientation questions had a similar proportion of missing responses (14% for sexual orientation vs. 14% for sleep), and only 13 respondents answered the sleep question without answering the sexual orientation question. Therefore, it was concluded that missingness on the sexual orientation item was likely due to survey fatigue as opposed to social desirability bias. Third, suicidal behavior is often stigmatized and may be underreported by respondents due to fears about disclosure to commanders and subsequent career consequences. However, the HRBS was self-administered online, and all responses were anonymous. These safeguards may have reduced the impact of social desirability bias. Lastly, the population in the present study may not be directly comparable to convenience samples of veteran populations. Comparisons between active component and veteran populations were made due to a relative lack of current literature regarding sexual orientation and suicide behaviors among active component populations.

LGB populations experience a disparate rate of suicide behavior when compared to heterosexual populations in both military and civilian settings; however, the magnitude of the disparity is unclear due to incomplete data reporting. Healthy People 2020 is the U.S. Federal Government’s effort to identify and address the most significant threats to the public’s health. For LGB individuals, Healthy People 2020 seeks to address systematic underreporting of sexual orientation data in an attempt to “increase the number of population-based data systems... that include in their core a standardized set of questions that identify lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations.”24

At the time of this study, a waiver is needed to ask questions on sexual orientation in the military.25 This requirement has resulted in a small number of studies that included survey questions that ask about sexual orientation. Although disparities in suicide behavior exist by sexual orientation, the lack of systematic data collection on sexual orientation means that the full extent of the disparities is not evident. The lack of data on sexual orientation in military settings is further compounded by the concern that reporting behaviors associated with suicidal behavior could jeopardize a service member’s career, resulting in a substantial reporting bias.26

Despite these difficulties, military clinical assessments of suicidal behavior should include collecting information on sexual orientation to more comprehensively assess its association with suicidal behavior. Furthermore, SMs should be encouraged to report their true mental health symptoms without fear of reprisal or career consequences. By more comprehensively assessing SM demographics and decreasing mental health stigma, military commanders and military healthcare providers will be able to more accurately assess SMs who are at risk for suicidal behavior, ensuring the health of their installation and maximizing the readiness of the Force.

Author affiliations

Division of Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes Practice, U.S. Army Public Health Center, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD (Dr. Beymer, Ms. Nichols, Dr. Watkins, Dr. Jarvis); Defense Health Agency, Falls Church, VA (Dr. Beymer, Ms. Nichols, Dr. Ambrose, Dr. Jeffery); General Dynamics Information Technology Inc., Falls Church, VA (Dr. Beymer); University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA (Dr. Shafir).

Acknowledgements

Analytic support was provided by the Behavioral and Social Health Outcome Practices (BSHOP) Division of the Army Public Health Center. Ethics approval: The Public Health Review Board of the Defense Health Agency approved this study as Public Health Practice under DHQ number DHQ-19-2020. Public health practice projects are not research as defined by Section 219.101, Title 32, Code of Federal Regulations, and do not require Institutional Review Board review or approval. Per DoDI 3216.02 Protection of Human Subjects and Adherence to Ethical Standards in DoD Conducted and Supported Research, the following activities conducted or supported by the DoD are not considered human subject research: activities carried out solely for purposes of diagnosis, treatment, or prevention of injury and disease under force health protection programs of DoD, including health surveillance pursuant to Section 1074f of Title 10, U.S.C., and the use of medical products consistent with DoDI 6200.02.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Army, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government.

References

1. National Center for Health Statistics. Increase in Suicide in the United States, 1999–2014. 2016; Accessed 28 March 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/databriefs/db241.htm

2. Heron M. Deaths: Leading causes for 2017. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019.

3. Stone DM, Simon TR, Fowler KA, et al. Vital Signs: Trends in State Suicide Rates - United States, 1999-2016 and Circumstances Contributing to Suicide - 27 States, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(22):617–624.

4. Haas AP, Eliason M, Mays VM, et al. Suicide and suicide risk in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations: review and recommendations. J Homosex. 2011;58(1):10–51.

5. Tucker RP. Suicide in Transgender Veterans: Prevalence, Prevention, and Implications of Current Policy. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019;14(3):452–468.

6. Lyons BH, Walters ML, Jack SPD, Petrosky E, Blair JM, Ivey-Stephenson AZ. Suicides Among Lesbian and Gay Male Individuals: Findings From the National Violent Death Reporting System. Am J Prev Med. 2019;56(4):512–521.

7. Stinchcombe A, Hammond NG. Sexual orientation as a social determinant of suicidal ideation: A study of the adult life span. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2021;51(5):864–871.

8. King M, Semlyen J, Tai SS, et al. A systematic review of mental disorder, suicide, and deliberate self-harm in lesbian, gay and bisexual people. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;18(8):70.

9. Mustanski BS, Garofalo R, Emerson EM. Mental health disorders, psychological distress, and suicidality in a diverse sample of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youths. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(12):2426–2432.

10. Liu RT, Mustanski B. Suicidal ideation and self-harm in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Am J Prev Med. 2012;42(3):221–228.

11. Mustanski B, Liu RT. A longitudinal study of predictors of suicide attempts among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth. Arch Sex Behav. 2013;42(3):437–448.

12. Ream GL. What's Unique About Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender (LGBT) Youth and Young Adult Suicides? Findings From the National Violent Death Reporting System. J Adolesc Health. 2019;64(5):602–607.

13. Liu RT, Walsh RFL, Sheehan AE, Cheek SM, Carter SM. Suicidal Ideation and Behavior Among Sexual Minority and Heterosexual Youth: 1995- 2017. Pediatrics. 2020;145(3):e20192221.

14. Barber ME. Mental health effects of don't ask don't tell. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2012;16(4):346–352.

15. Bodon N. An Iraq Veteran's Story. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health. 2012;16(4):334–337.

16. Cianni V. Gays in the Military: How America Thanked Me. J Gay Lesbian Ment Health. 2012;16(4):322–333.

17. Blosnich JR, Bossarte RM, Silenzio VM. Suicidal ideation among sexual minority veterans: results from the 2005-2010 Massachusetts Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance Survey. Am J Public Health. 2012;102 Suppl 1:S44–47.

18. Sexton MB, Davis MT, Anderson RE, Bennett DC, Sparapani E, Porter KE. Relation between sexual and gender minority status and suicide attempts among veterans seeking treatment for military sexual trauma. Psychol Serv. 2018;15(3):357–362.

19. Lynch KE, Gatsby E, Viernes B, et al. Evaluation of Suicide Mortality Among Sexual Minority US Veterans From 2000 to 2017. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2031357.

20. Matarazzo BB, Barnes SM, Pease JL, et al. Suicide risk among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender military personnel and veterans: what does the literature tell us? Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2014;44(2):200–217.

21. Jeffery DD, Beymer MR, Mattiko MJ, Shell D. Health Behavior Differences Between Male and Female U.S. Military Personnel by Sexual Orientation: The Importance of Disaggregating Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Groups. Mil Med. 2021;186(5-6):556–564.

22. Meadows SO, Engel CC, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS). Rand Health Q. 2018;8(2):5.

23. Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey of Active Duty Military Personnel. 2011; Accessed 30 March 2022. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2013/02/01/2011-Health-Related-Behaviors-Active-Duty-Executive-Summary

24. HealthyPeople.gov. Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health. 2020; Accessed 18 August 2021. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/lesbian-gay-bisexual-andtransgender-health/objectives

25. Under Secretary of Defense. Certification of the Repeal of “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”. 2011; Accessed 30 March 2022.https://www.iimef.marines.mil/Portals/1/documents/IG/Certification%20of%20Repeal%20of%20Don't%20Ask%20Don't%20Tell%20Jul%202011.pdf

26. Kazman JB, Gutierrez IA, Schuler ER, et al. Who sees the chaplain? Characteristics and correlates of behavioral health care-seeking in the military. J Health Care Chaplain. 2020:1–12.