Exertional hyponatremia occurs either during or following periods of heavy exertion, when losses of water and electrolytes due to the body’s normal cooling mechanisms are replaced only with water. Hyponatremia can lead to death or serious morbidity if left untreated. Between 2007 and 2022, there were 1,690 diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia among active component service members, for an overall incidence rate of 7.9 cases per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs). Those younger than 20 years or older than 40, non-Hispanic White service members, Marine Corps members, and recruit trainees had higher overall rates of exertional hyponatremia diagnoses. Between 2007 and 2022, annual rates of incident exertional hyponatremia diagnoses peaked (12.7 per 100,000 p-yrs) in 2010 and then decreased to a low of 5.3 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2013. During the last 9 years of the surveillance period, rates fell between a range of 6.1 and 8.6 cases per 100,000 p-yrs. Service members and their supervisors must know the dangers of excessive water consumption and prescribed limits for water intake during prolonged physical activity, such as field training exercises, personal fitness training, as well as recreational activities, particularly in hot, humid weather.

What are the new findings?

The vast majority of exertional hyponatremia cases were treated in outpatient settings, suggesting that most cases were identified during the early and less severe stages.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Exertional hyponatremia continues to pose a health risk to U.S. military members and can be fatal if not promptly recognized and appropriately treated. Military members, leaders, and trainers must be vigilant for early signs of hyponatremia, intervene immediately and appropriately, and observe the published guidelines for proper hydration during physical exertion, especially during hot weather.

Background

Exertional hyponatremia, or exercise-associated hyponatremia, refers to a low plasma sodium concentration (below 135 milliequivalents per liter) that develops within 24 hours of prolonged physical activity.1 Exertional hyponatremia usually results from consumption of large volumes of water in a short time. Acute hyponatremia creates an osmotic gradient that causes water to flow into the cells of various organs, including the lungs and brain, producing serious and sometimes fatal clinical effects.1,2 Exertional hyponatremia can result from loss of sodium or potassium, relative body water excess, or a combination of both,3 but overconsumption of fluids and a resultant excess of total body water are the primary factors in the development of exertional hyponatremia.1,3,4

Exertional hyponatremia has been described in relation to a variety of activities including endurance competitions, hiking, police training, American football, fraternity hazing, and military exercises.1 Hyponatremia incidence from these events varies widely, and is dependent upon activity duration, stress from heat or cold, water availability, and other risk factors. Water consumption in volumes greater than its loss through sweat, respiration, and renal excretion remains the single most important risk factor.1 The amount of excess water consumption required to induce exertional hyponatremia is substantial. In an outbreak among Marine recruits in 1995, between 10 and 22 quarts of water were consumed by each person over a few hours.5 In endurance sports competitions, lack of acclimatization to local environmental conditions is another risk factor for exertional hyponatremia.6 Other important risk factors include an exercise duration greater than 4 hours, inadequate event training, and either a high or low body mass index.1

Exertional hyponatremia continues to pose a health risk to U.S. military members that can significantly impair performance and reduce combat effectiveness. This report summarizes the frequencies, rates, trends, geographic locations, and both demographic and military characteristics of incident cases of exertional hyponatremia among active component service members, from 2007 to 2022.

Methods

The surveillance population for this report consists of all active component service members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps who served at any time during the surveillance period, from January 1, 2007 to December 31, 2022. All data used to determine incident exertional hyponatremia diagnoses were derived from records routinely collected and maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). These records document both ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System [MHS]) treatment facilities worldwide. In-theater diagnoses of hyponatremia were identified from medical records of service members deployed to Southwest Asia or the Middle East and whose health care encounters were documented in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS).

For this report, a case of exertional hyponatremia was defined as 1) a hospitalization or ambulatory visit with a primary (first-listed) diagnosis of “hypoosmolality and/or hyponatremia” (International Classification of Diseases, 9th and 10th Revisions, ICD-9: 276.1; ICD-10: E87.1) and no other illness or injury-specific diagnoses (ICD-9: 001–999; ICD-10: A–U) in any diagnostic position or 2) both a diagnosis of “hypoosmolality and/or hyponatremia” (ICD-9: 276.1; ICD-10: E87.1) and at least 1 of the following within the first 3 diagnostic positions (dx1–dx3): “fluid overload” (ICD-9: 276.9; ICD-10: E87.70, E87.79), “alteration of consciousness” (ICD-9: 780.0*; ICD-10: R40.*), “convulsions” (ICD-9: 780.39; ICD-10: R56.9), “altered mental status” (ICD-9: 780.97; ICD-10: R41.82), “effects of heat/light” (ICD-9: 992.0–992.9; ICD-10: T67.0*–T67.9*), or “rhabdomyolysis” (ICD-9: 728.88; ICD-10: M62.82).7

Medical encounters were not considered case-defining events if the associated records included the following diagnoses in any diagnostic position: alcohol/illicit drug abuse; psychosis, depression, or other major mental disorders; endocrine disorders; kidney diseases; intestinal infectious diseases; cancers; major traumatic injuries; or complications of medical care. An individual could be considered a case of exertional hyponatremia only once per calendar year. Incidence rates were calculated as cases of hyponatremia per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) of active component service. Percent change in incidence was calculated using unrounded rates. At the time of this analysis, Army personnel data were not available for November and December 2022. To calculate person-time for Army members during this period, the October personnel data were used.

For health surveillance purposes, recruit trainees were identified as active component members assigned to service-specific training locations during coincident service-specific basic training periods. Because of the lack of personnel data in November and December 2022, Army members who started basic training during this period were not counted as recruits. Recruit trainees were considered a separate category of enlisted service members in summaries of heat illnesses by overall military grade.

In-theater diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia were analyzed separately using the same case-defining criteria and incidence rules used to identify incident cases at fixed treatment facilities. Records of medical evacuations from the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) (i.e., Southwest Asia/Middle East) to a medical treatment facility outside the CENTCOM AOR were analyzed separately. Evacuations were considered case-defining if the affected service members met the aforementioned criteria in a permanent military medical facility in the U.S. or Europe, from 5 days preceding until 10 days following their evacuation dates.

Medical data from sites using the new electronic health record for the Military Health System, MHS GENESIS, between July 2017 and October 2019 are not available in the DMSS and thus not included in this report—these sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center.

Results

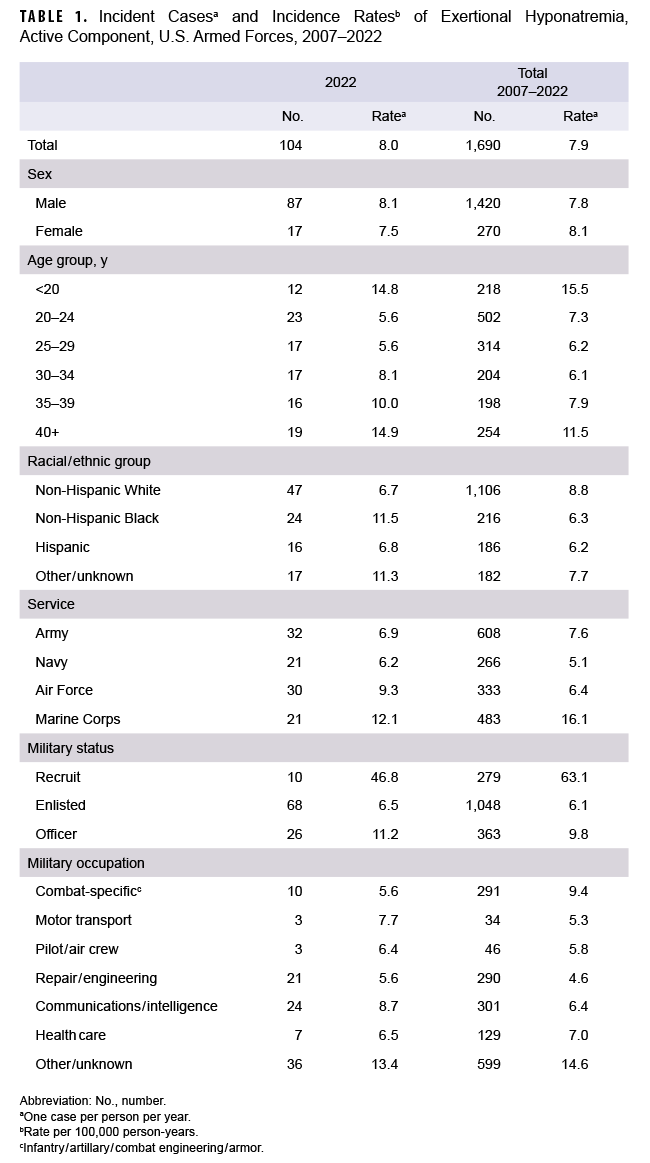

In 2022, there were 104 diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia among active component service members, with a crude incidence rate of 8.0 per 100,000 p-yrs (Table 1).

The 2022 incidence rate patterns were broadly similar by demographic and military characteristics to those in prior years. Demographic categories are presented as cumulative rates to promote rate stability, since stratification of the annual rates yielded frequencies of less than 20 in more than 40% of the table sub-categories.

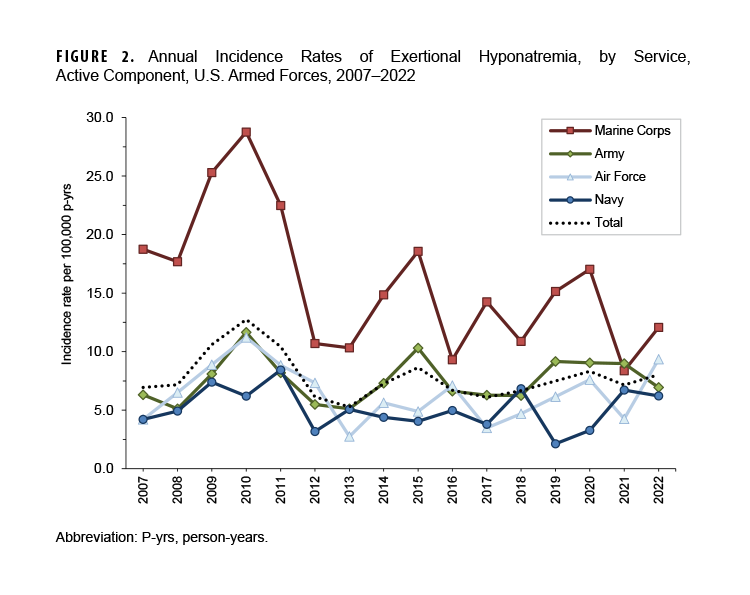

Between 2007 and 2022, men represented the vast majority (84.0%) of exertional hyponatremia cases but had an incidence rate comparable to women (Table 1). Subgroup-specific incidence rates were highest among those in the youngest (under 20 years) and oldest (40 years or older) age groups, non-Hispanic White service members, Marine Corps members, and recruit trainees. The rate of hyponatremia among Marine Corps members was markedly higher than the rates of those in other services. Although recruit trainees accounted for approximately one-sixth (16.5%) of all exertional hyponatremia cases, their crude incidence rate was 10.4 and 6.5 times the rates among other enlisted members and officers, respectively.

During the 16-year period, 86.8% (n=1,467) of all cases were diagnosed and treated without hospitalization (Figure 1).

![This graph shows stacked columns for each of the years 2007 through 2022. Each year’s stacked column is divided into 2 segments that indicate the numbers of cases of exertional hyponatremia identified among service members via ambulatory visits (in the lower segment) or hospitalizations (in the upper segment). A solid horizontal line connects points representing the crude annual incidence rates of all identified cases of exertional hyponatremia among service members in the active component. Between 2007 and 2022, crude annual rates of incident exertional hyponatremia diagnoses peaked in 2010 (at 12.7 per 100,000 person-years [or p-yrs]) and then decreased to a low of 5.3 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2013. Following a nadir in 2013, the crude annual rate rose to 8.6 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2015, thereafter decreasing through 2017. Crude annual rates rose again in 2018, 2019, and 2020, reaching 8.3 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2020, then decreasing to 7.1 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2021, and increasing to 8.0 in 2022.](/-/media/Images/MHS/Photos/AFHSB-MSMR/2023/April/Article-4-Figure-1.ashx?h=588&w=750&hash=D2178A41EEFAB8335E212DD9E3F8A15DCB61C795)

Between 2007 and 2022, the crude annual rates of incident exertional hyponatremia diagnoses peaked in 2010 (12.7 per 100,000 p-yrs) and then decreased to a low of 5.3 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2013 (Figure 1). During the last 9 years of the surveillance period, rates fluctuated between 6.1 and 8.6 cases per 100,000 p-yrs. With the exception of 2021, annual incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia diagnoses were markedly higher in the Marine Corps than in other services (Figure 2).

Exertional hyponatremia by location

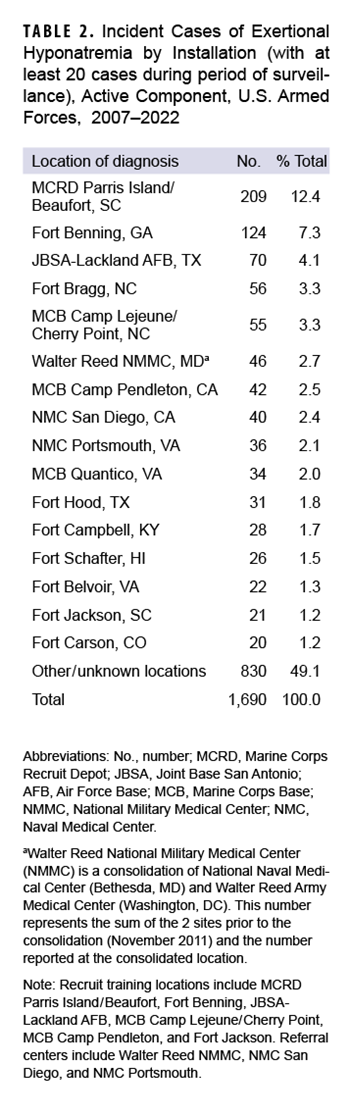

During the 16-year surveillance period, exertional hyponatremia cases were diagnosed at more than 150 U.S. military installations and geographic locations worldwide, but 16 U.S. installations contributed 20 or more cases each and accounted for 50.9% of total cases (Table 2).

Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) Parris Island/Beaufort, SC reported 209 cases of exertional hyponatremia, the highest in the DOD.

Exertional hyponatremia in the CENTCOM AOR

Between 2007 and 2022, a total of 23 cases of exertional hyponatremia were diagnosed and treated in the CENTCOM AOR (data not shown). Two new cases were diagnosed in 2022. Deployed service members affected by exertional hyponatremia were most frequently male (n=19; 82.6%), non-Hispanic White (n=19; 82.6%), 20-24 years old (n=10; 43.5%), in the Army (n=14; 60.9%), enlisted (n=19; 82.6%), and in combat-specific (n=7; 30.4%) or communications/intelligence (n=6; 26.1%) occupations (data not shown). Seven service members were medically evacuated from the CENTCOM AOR for exertional hyponatremia, in 2007 or 2018 (data not shown).

Discussion

For the last decade, incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia have remained relatively stable among active component service members. Subgroup-specific patterns (e.g., age, racial/ethnic group, service, and military status) of overall incidence rates were generally similar to those reported in previous MSMR updates.8 In MSMR analyses before April 2018, in-theater cases included diagnoses of hypoosmolality and/or hyponatremia in any diagnostic position, but in 2018 case-defining criteria for inpatient and outpatient encounters were applied to in-theater encounters. As a result, the results of the in-theater analysis are not comparable to those presented in earlier MSMR updates.

Recruits remain at high risk for exertional hyponatremia. In this report, rates were relatively high among the youngest, hence most junior service members, with highest case numbers diagnosed at medical facilities that support large recruit training centers (e.g., MCRD Parris Island/Beaufort, SC; Fort Benning, GA; Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland Air Force Base, TX) and large Army and Marine Corps combat units (e.g., Fort Bragg, NC; Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune/Cherry Point, NC).

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting these results. First, there is no diagnostic code specific for exertional hyponatremia. This lack of specificity may result in the inclusion of some non-exertional cases of hyponatremia, thus overestimating the true rate. Consequently, these results should be considered estimates of the actual incidence of symptomatic exertional hyponatremia from excessive water consumption among U.S. military members. In addition, the accuracy of estimated numbers, rates, trends, and correlates of risk depends on the completeness and accuracy of diagnoses documented in standardized records of relevant medical encounters. As a result, an increase in recorded diagnoses indicative of exertional hyponatremia may reflect, at least in part, increasing awareness, concern, and aggressive management for incipient cases by military supervisors and primary health care providers.

Finally, recruit trainees were identified using an algorithm based on age, rank, location, and time in service, which was only an approximation and likely resulted in some misclassification of recruit training status. The imputation used to address the gap in Army personnel data from November and December 2022 is another potential source of misclassification that may have resulted in underestimation of Army recruits and periods of recruit training during the last 2 months of 2022. Due to this data discrepancy, recruit rates should be interpreted with caution.

Military training may have to be conducted in difficult conditions, and during hot and humid weather commanders, supervisors, instructors, and medical support staff must be aware of, monitor, and enforce guidelines for work-rest cycles and water consumption.2 The continued necessity of training and operations under challenging environmental conditions creates a high-risk environment for exertional hyponatremia and other heat illnesses. While the rates of exertional hyponatremia have remained relatively low over the past 15 years, the Defense Health Agency continues to publish practice recommendations intended to guide the prevention, assessment, and management of exercise associated hyponatremia.10 Thoughtful risk assessment and planning are necessary for keeping this preventable illness at its current low levels.

References

- Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the Third International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25(4):303-320. doi:10.1097/JSM.0000000000000221

-

Buchanan BK, Sylvester JE, DeGroot DW. Exercise associated hyponatremia practice recommendation. March 17, 2021. Accessed March 12, 2023. https://www.hprc-online.org/sites/default/files/document/HPRC_WHEC_Exercise Associated Hyponatremia Practice Recommendation_508_0.pdf

-

Nguyen MK, Kurtz I. Determinants of plasma water sodium concentration as reflected in the Edelman equation: role of osmotic and Gibbs-Donnan equilibrium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286(5):F828-F837. doi:10.1152/ajprenal.00393.2003

-

Noakes TD, Sharwood K, Speedy D, et al. Three independent biological mechanisms cause exercise-associated hyponatremia: evidence from 2,135 weighed competitive athletic performances. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(51):18550-18555. doi:10.1073/pnas.0509096102

-

Bennett BL, Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Myers T, Lipman GS. Wilderness Medical Society clinical practice guidelines for the management of exercise-associated hyponatremia: 2019 update. Wilderness Environ Med. 2020;31(1):50-62. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2019.11.003

-

Gardner JW. Death by water intoxication. Mil Med. 2002;167(5):432-434. doi:10.1093/milmed/167.5.432

-

Martinez-Sanz JM, Nunez AF, Sospedra I, et al. Nutrition-related adverse outcomes in endurance sports competitions: a review of incidence and practical recommendations. Int J Environ Res Pub Health. 2020;17(11):4082. doi:10.3390/ijerph17114082

-

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance Case Definition. Hyponatremia. March 2017. Accessed March 20, 2023. //Reference-Center/Publications/2017/03/01/Hyponatremia-Exertional

-

Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: exertional hyponatremia, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2006–2022. MSMR. 2022;29(4):21-26.

-

Buchanan BK, Sylvester, JE, DeGroot DW. Exercise Associated Hyponatremia. Defense Health Agency. January 2022. Accessed April 25, 2023. https://www.hprc-online.org/sites/default/files/document/DHA_PR_Exercise_Associated_Hyponatremia_25Aug22_508.pdf