Abstract

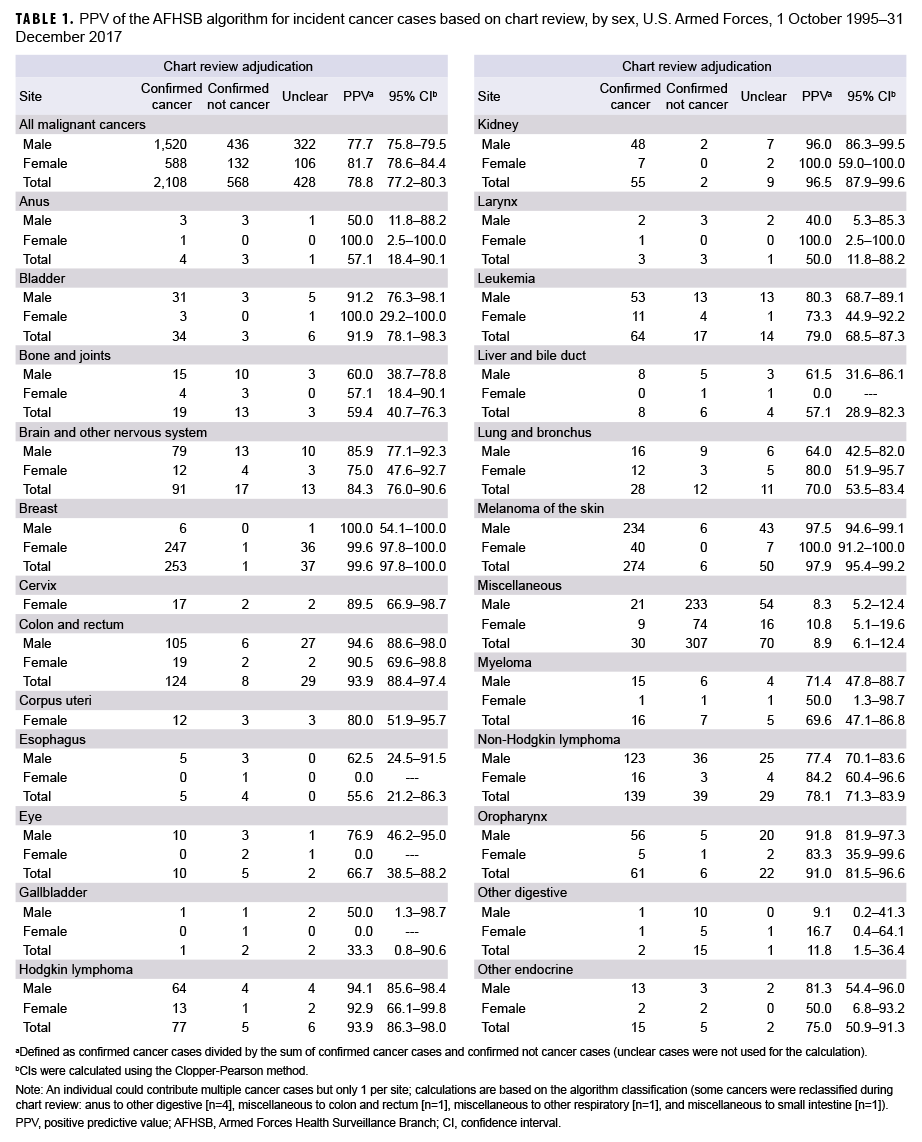

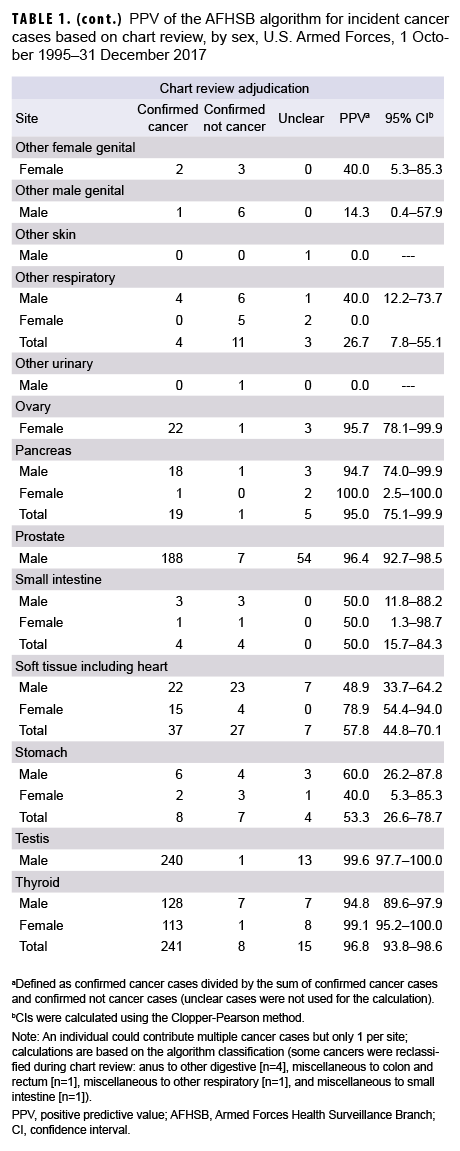

Recent large-scale epidemiologic studies of cancer incidence in the U.S. Armed Forces have used International Classification of Disease, 9th and 10th Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively) diagnostic codes from administrative medical encounter data archived in the Defense Medical Surveillance System. Cancer cases are identified and captured according to an algorithm published by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Standardized chart reviews were performed to provide a gold standard by which to validate the case definition algorithm. In a cohort of active component U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps officers followed from 1 Oct. 1995 through 31 Dec. 2017, a total of 2,422 individuals contributed 3,104 algorithm-derived cancer cases. Of these cases, 2,108 (67.9%) were classified as confirmed cancers, 568 (18.3%) as confirmed not cancers, and 428 (13.8%) as unclear. The overall positive predictive value (PPV) of the algorithm was 78.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 77.2–80.3). For the 12 cancer sites with at least 50 cases identified by the algorithm, the PPV ranged from a high of 99.6% for breast and testicular cancers (95% CI: 97.8–100.0 and 97.7–100.0, respectively) to a low of 78.1% (95% CI: 71.3–83.9) for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Of the 568 cases confirmed as not cancer, 527 (92.7%) occurred in individuals with at least 1 other confirmed cancer, suggesting algorithmic capture of metastases as additional primary cancers.

What Are the New Findings?

The cancer case definition algorithm published by the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch had a high PPV for capturing cases of common cancers and a low-to-moderate PPV for rarer cancers.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

In the absence of a comprehensive centralized registry, cancer surveillance in the Department of Defense can rely on the Defense Medical Surveillance System for common cancer types. Algorithm-derived cases of rarer cancers may require verification by chart review.

Background

Formal cancer surveillance dates to the early 17th century, when cancer was first recorded as a cause of death in England's Bills of Mortality.1 A cancer registry for London followed in the 18th century, and the first population-based cancer registry in the U.S. appeared in 1935.1 The Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) program, established by the National Cancer Institute in 1973, was the first national cancer registry in the United States.1 Now a conglomerate of 18 registries representing approximately 30% of the U.S. population, the SEER program utilizes the International Classification of Diseases for Oncology (ICD-O) taxonomy and incorporates demographic, clinical, histopathologic, and molecular data.2

The Automated Central Tumor Registry (ACTUR) has been the centralized cancer registry for the Department of Defense since its launch in 1986.3 Several studies that have utilized this registry, however, report concerns with data incompleteness.4–7 This incompleteness has not been quantified, but Zhu and colleagues note that some military treatment facilities (MTFs) do not comprehensively report cancer diagnoses to the ACTUR.4 Recent large-scale epidemiologic studies of incident cancer in the U.S. Armed Forces have relied on diagnostic codes captured in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS),8–10 using Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch (AFHSB) case definitions.11 This validation study provides chart review adjudication of cancer cases captured by the AFHSB cancer case definition algorithm.

Methods

As part of a public health surveillance activity, the Epidemiology Consult Service Division (Public Health and Preventive Medicine Department, U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine), received oncological ICD 9th and 10th Revision (ICD-9 and ICD-10, respectively) codes of interest from AFHSB for active component U.S. Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps officers who entered service as company grade officers between 1 Jan. 1986 and 31 Dec. 2006. The outcome period was 1 Oct. 1995 through 31 Dec. 2017. The outcome start date corresponds to the beginning of outpatient data capture in the DMSS, which includes diagnostic codes for all inpatient visits and outpatient encounters at MTFs (i.e., Click to closeDirect CareDirect care refers to military hospitals and clinics, also known as “military treatment facilities” and “MTFs.”direct care) or at outside facilities reimbursed by TRICARE (i.e., Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care).12 All ICD codes recorded during inpatient and outpatient encounters during the outcome surveillance period were obtained regardless of beneficiary status (i.e., active duty, guard/reserve, retired, or family member).

Potential cancer cases were initially identified by searching for all cancer-related ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes in any diagnostic position from inpatient visits and outpatient encounters. Because they are not reportable to central cancer registries, basal and squamous cell skin cancers were excluded. All other malignant cancers were categorized using the SEER site-specific ICD conversion program.13

As of this writing, AFHSB has published case definitions for 117 unique conditions, of which 11 are oncologic: breast cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, leukemia, lung cancer, malignant brain tumor, melanoma of the skin, non-Hodgkin lymphoma, non-melanomatous skin cancer, prostate cancer, and testicular cancer. With the exception of skin cancers, oncologic case definition algorithms specify 3 criteria by which ICD codes may classify as cases: 1) a hospitalization with a diagnostic code in the primary diagnostic position, 2) a hospitalization with a diagnostic code in the secondary diagnostic position and a therapeutic treatment V code in the primary position, or 3) 3 or more outpatient encounters within a 90-day period with a diagnostic code in the primary or secondary position. These classifications will be denoted as inpatient, inpatient plus therapy, and outpatient, respectively. This algorithm was applied to all site-specific cancers—including to those without an AFHSB published case definition—and to melanoma of the skin, which has a different case definition algorithm.14 The oncological case definition was applied to melanoma of the skin in order to maximize standardization. Data were managed and analyzed using Base SAS and SAS/STAT® software, version 9.4 (2014, SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Novel code was written to apply the AFHSB case definition algorithm. For individuals identified as having more than 1 site-specific cancer, all cancers captured by the algorithm were included.

All unique cancer cases identified by the algorithm (n=3,104) were chart reviewed by 2 physicians (BJW for Air Force personnel; AER for Navy and Marine Corps personnel) using the Armed Forces Health Longitudinal Technology Application (AHLTA), Health Artifact and Image Management Solution (HAIMS), and Joint Legacy Viewer (JLV). Algorithmically captured cases were adjudicated as either confirmed cancer, confirmed not cancer, or unclear. A case was defined as confirmed cancer if it met any of these criteria: 1) a diagnosis made by an oncologist or general surgeon; 2) a diagnosis of specific cancers made by the appropriate medical or surgical specialist (i.e., melanoma of the skin by a dermatologist; thyroid cancer by an endocrinologist; eye cancer by an ophthalmologist; brain cancer by a neurologist or neurosurgeon; lung and bronchus cancer by a pulmonologist; bone and joint cancer by an orthopedist; prostate or testicular cancer by a urologist; kidney or bladder cancer by a nephrologist; colorectal, anal, or stomach cancer by a gastroenterologist; and cervical, corpus uteri, or ovarian cancer by a gynecologist); or 3) a diagnosis made by a primary care provider with substantiating documentation in the clinical note, such as histopathologic or treatment information. A case was defined as confirmed not cancer if an alternative diagnosis was found that explained the ICD code(s) captured by the algorithm. A case was defined as unclear if chart documentation was insufficient for making a determination.

All cancers were considered incident conditions, with the incident (i.e., diagnosis) date corresponding to the date of the first ICD code contributing to the case criterion. If, on chart review, the code was related to a history of cancer (i.e., a prevalent rather than incident case), the case was classified as unclear. These cases were not classified as confirmed not cancer because recurrence could not be excluded. For individuals with multiple cancers, each cancer site was assigned its own incident date.

For all malignant cancers and site-specific cancers, total and sex-specific positive predictive values (PPVs) with 95% binomial-based Clopper-Pearson confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. PPV was also calculated after stratifying by the 3 criteria used to capture cases. PPV was defined as the number of confirmed cancer cases divided by the sum of confirmed cancer and confirmed not cancer cases; unclear cases were not included in the calculation. Although chart review resulted in site reclassification for some confirmed cancer cases, PPVs were calculated according to the original, algorithmically defined site. This study was approved by the Air Force Research Laboratory Institutional Review Board.

Results

A total of 133,843 hospitalization and outpatient encounter records from 5,787 persons with a cancer ICD-9 or ICD-10 code in any diagnostic position (Air Force, n=93,174; Navy/Marine Corps, n=40,669) during the outcome period of 1 Oct. 1995 through 31 Dec. 2017 were abstracted by AFHSB. After application of the AFHSB algorithm, 3,104 unique cancer cases were identified among 2,422 individuals. Based on chart review, 2,108 (67.9%) were classified as confirmed cancers, 568 (18.3%) as confirmed not cancers, and 428 (13.8%) as unclear. The algorithm's PPV for all malignant cancers was 78.8% (95% CI: 77.2–80.3); for males it was 77.7% (95% CI: 75.8–79.5); for females it was 81.7% (95% CI: 78.6–84.4). For the 12 sites with at least 50 total cancer cases captured by the algorithm, the PPV ranged from a high of 99.6% for cancer of the breast and cancer of the testis (95% CI: 97.8–100.0 and 97.7–100.0, respectively) to a low of 78.1% (95% CI: 71.3–83.9) for non-Hodgkin lymphoma (Table 1).

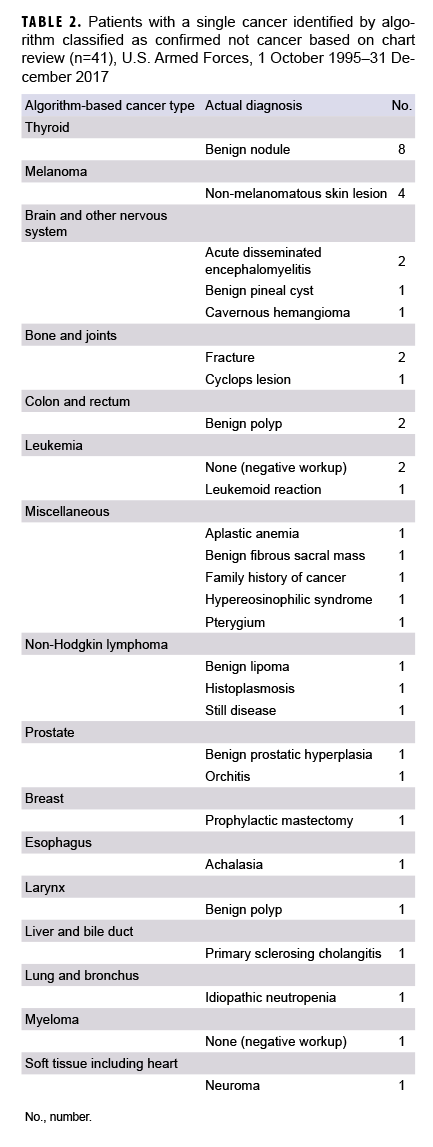

Of the 568 cases confirmed as not cancer, 527 (92.7%) occurred in individuals with at least 1 other confirmed cancer (data not shown). Among the 41 cases of ruled-out cancer without a separate confirmed case, the most common situations were benign thyroid nodules algorithmically captured as thyroid cancer (n=8) and non-melanomatous skin lesions captured as melanoma of the skin (n=4) (Table 2). An additional 7 cases were reclassified based on chart review: anus to other digestive (n=4), miscellaneous to colon and rectum (n=1), miscellaneous to other respiratory (n=1), and miscellaneous to small intestine (n=1) (data not shown).

Confirmed cases were captured predominantly by criterion #3 (outpatient) (n=2,034), followed by criterion #1 (inpatient) (n=915) and criterion #2 (inpatient plus therapy) (n=44); some cases (n=885) were captured by multiple criteria. PPVs were 81.7% (95% CI: 79.3–83.9) for inpatient, 62.9% (95% CI: 50.5–74.1) for inpatient plus therapy, and 80.7% (95% CI: 79.1–82.2) for outpatient. Inpatient and outpatient PPVs were statistically equivalent for each cancer type (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

Common cancers captured by the AFHSB case definition algorithm usually reflected true cases, with PPVs exceeding 95% for breast, melanoma of the skin, prostate, testis, and thyroid cancers. In the absence of tumor registry data, epidemiologic studies of these cancers can rely on the AFHSB algorithm without confirmatory chart reviews. For studies of rarer cancers, such as bone and joint, esophagus, or liver and bile duct cancers—all of which had PPVs below 60%—investigators may want to confirm cases by chart review or adjust for misclassification in order to avoid overcounting cases. Such adjustment assumes that the degree of misclassification bias remains constant over time.

Investigators should also be cautious when individuals are identified by the algorithm as having more than 1 cancer. Over 92% of the cancers that were excluded during chart review were in individuals with at least 1 other confirmed cancer, suggesting capture of metastases as additional primary cancers. For surveillance purposes, investigators interested in overall cancer rates may consider limiting case counting to 1 per individual per lifetime. For site-specific cancer epidemiology, investigators may need to conduct chart reviews of individuals with multiple cancers to distinguish multiple primary cancers from solitary primary cancers with metastases. Investigators may also want to perform chart reviews of cases identified only by the inpatient plus therapy criterion, as this had a lower overall PPV than the other criteria, although this low PPV was largely driven by misclassification of miscellaneous cancers.

The high PPV for melanoma of the skin (PPV: 97.9%; 95% CI: 95.4–99.2) suggests that the standard AFHSB oncological case definition can be applied to this cancer type. Future research could determine if the AFHSB case definition for melanoma of the skin14 outperforms the standard oncological case definition.

This study has at least 2 limitations. First, nearly 14% of all algorithm-defined cancer cases could not be definitively categorized during chart review as either cancer or not cancer. The diagnostic codes responsible for these cases may have been generated outside MTFs (i.e., in TRICARE purchased care settings), and documents from these hospitalizations or outpatient encounters were not uploaded into the HAIMS. It is unclear if their inclusion would increase or decrease PPV estimates. Second, in the absence of a registry or another database with 100% case capture, which may include cancer cases not captured by the AFHSB algorithm, this study cannot provide information on the algorithm's sensitivity. A future study should compare the AHFSB algorithm with data from the ACTUR; such a study may need to be restricted to military treatment facilities that systematically report cancer cases to the registry.

The AFHSB cancer case definition algorithm is a valuable surveillance tool for accurately identifying the most common cancers, although it has a lower PPV for rarer cancers. Since the DMSS does not provide information on critical variables such as histology and staging, the ACTUR should be funded to enhance oncology research and surveillance. Warfighters encounter unique environmental and occupational hazards, with more notable examples including herbicides in Vietnam, oil fires in Kuwait, and burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan.15 Tracking exposures and linking them to long-term outcomes—malignancy chief among them—is a critical capability for protecting the health of service members and veterans.16,17

Author affiliations: Public Health and Preventive Medicine Department, U.S. Air Force School of Aerospace Medicine, Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, OH (Maj Webber, Lt Col Robbins); Navy Environmental and Preventive Medicine Unit TWO, Naval Station Norfolk, VA (LCDR Rogers); DataRev LLC, Atlanta, GA (Ms. Pathak); Solutions Through Innovative Technologies, Inc., Fairborn, OH (Ms. Pathak)

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Air Force, the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. Government. The authors are either military service members or contract employees of the U.S. Government. This work was prepared as part of their official duties. Title 17, U.S.C., §105 provides that copyright protection under this title is not available for any work of the U.S. Government. Title 17, U.S.C., §101 defines a U.S. Government work as a work prepared by a military service member or employee of the U.S. Government as part of that person's official duties.

References

- National Cancer Institute. Historical events. https://training.seer.cancer.gov/registration/registry/history/dates.html. Accessed 31 Oct. 2019.

- Park HS, Lloyd S, Decker RH, Wilson LD, Yu JB. Overview of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database: evolution, data variables, and quality assurance. Curr Probl Cancer. 2012;36(4):183–190.

- The Joint Pathology Center. DOD Cancer Registry Program. https://www.jpc.capmed.mil/education/dodccrs/index.asp. Accessed 31 Oct. 2019.

- Zhu K, Devesa SS, Wu H, et al. Cancer incidence in the U.S. military population: comparison with rates from the SEER program. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18(6):1740–1745.

- Zhou J, Enewold L, Zahm SH, et al. Melanoma incidence rates among whites in the U.S. Military. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(2):318–323.

- Enewold LR, Zhou J, Devesa SS, et al. Thyroid cancer incidence among active duty U.S. military personnel, 1990–2004. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2011;20(11):2369–2376.

- Lea CS, Efird JT, Toland AE, Lewis DR, Phillips CJ. Melanoma incidence rates in active duty military personnel compared with a population-based registry in the United States, 2000–2007. Mil Med. 2014;179(3):247–253.

- Lee T, Williams VF, Taubman SB, Clark LL. Incident diagnoses of cancers in the active component and cancer-related deaths in the active and reserve components, U.S. Armed Forces, 2005–2014. MSMR. 2016;23(7):23–31.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Incident diagnoses of cancers and cancer-related deaths, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, January 2000–Dec. 2009. MSMR. 2010;17(6):2–6.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Center. Incident diagnoses of cancers and cancer-related deaths, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2011. MSMR. 2012;19(6):18–22.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance case definitions. https://www.health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Epidemiologyand-Analysis/Surveillance-Case-Definitions. Accessed 31 Oct. 2019.

- Rubertone MV, Brundage JF. The Defense Medical Surveillance System and the Department of Defense serum repository: glimpses of the future of public health surveillance. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(12):1900–1904.

- National Cancer Institute. ICD conversion programs. https://seer.cancer.gov/tools/conversion/. Accessed 31 Oct. 2019.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance case definition: Malignant melanoma; skin. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Publications/2016/05/01/Malignant-melanoma. Accessed 31 Oct. 2019.

- Gaydos JC. Military occupational and environmental health: challenges for the 21st century. Mil Med. 2011;176(7 suppl):5–8.

- DeFraites RF, Richards EE. Assessing potentially hazardous environmental exposures among military populations: 2010 symposium and workshop summary and conclusions. Mil Med. 2011;176(7 suppl):17–21.

- Institute of Medicine. Protecting Those Who Serve: Strategies to Protect the Health of Deployed U.S. Forces. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2000.