Abstract

From 2004 through 2019, there were 1,612 incident diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia among active component service members, for a crude overall incidence rate of 7.4 cases per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs). Compared to their respective counterparts, females, those less than 20 years old, and recruit trainees had higher overall incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia diagnoses. The overall incidence rate during the 16-year period was highest in the Marine Corps, intermediate in the Army and Air Force, and lowest in the Navy. Overall rates during the surveillance period were highest among Asian/Pacific Islander and non-Hispanic white service members and lowest among non-Hispanic black service members. Between 2004 and 2019, crude annual incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia peaked in 2010 at 12.7 per 100,000 p-yrs and then decreased to a low of 5.3 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2013. The crude annual rates fluctuated between 2014 and 2019, reaching the 2 highest rates in 2015 (8.6 per 100,000 p-yrs) and in 2019 (7.1 per 100,000 p-yrs). Service members and their supervisors must be knowledgeable of the dangers of excessive water consumption and the prescribed limits for water intake during prolonged physical activity (e.g., field training exercises, personal fitness training, and recreational activities) in hot, humid weather.

What Are the New Findings?

Annual incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia in service members have risen slightly during the past 2 years but remained well below the peak rates of 2009–2011. As in previous years, rates of exertional hyponatremia were highest among service members under 20 years of age, recruit trainees, Marines, and those in combat-specific occupations.

What Is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

Exertional hyponatremia can not only reduce operational readiness by causing considerable morbidity, particularly among recruit trainees and Marine Corps and Army members in combat arms specialties, but it occasionally causes death. Service members, leaders, and trainers must observe the published guidelines that pertain to proper hydration during physical exertion, especially during warm weather.

Background

Exertional (or exercise-associated) hyponatremia refers to a low serum, plasma, or blood sodium concentration (below 135 mEq/L) that develops during or up to 24 hours following prolonged physical activity.1 Acute hyponatremia creates an osmotic imbalance between fluids outside and inside of cells. This osmotic gradient causes water to flow from outside to inside the cells of various organs, including the lungs (which can cause pulmonary edema) and brain (which can cause cerebral edema), producing serious and sometimes fatal clinical effects.1,2 Swelling of the brain increases intracranial pressure, which can decrease cerebral blood flow and disrupt brain function, potentially causing hypotonic encephalopathy, seizures, or coma. Rapid and definitive treatment is needed to relieve increasing intracranial pressure and prevent brain stem herniation, which can result in respiratory arrest.2–4

Serum sodium concentration is determined mainly by the total content of exchangeable body sodium and potassium relative to total body water. Thus, exertional hyponatremia can result from loss of sodium and/or potassium, a relative excess of body water, or a combination of both.5,6 However, overconsumption of fluids and the resultant excess of total body water are the primary driving factors in the development of exertional hyponatremia.1,7,8 Other important factors include the persistent secretion of antidiuretic hormone (arginine vasopressin), excessive sodium losses in sweat, and inadequate sodium intake during prolonged physical exertion, particularly during heat stress.2–4,9 The importance of sodium losses through sweat in the development of exertional hyponatremia is influenced by the fitness level of the individual. Less fit individuals generally have a higher sweat sodium concentration, a higher rate of sweat production, and an earlier onset of sweating during exercise.10–12

This report uses a surveillance case definition for exertional hyponatremia to estimate the frequencies, rates, trends, geographic locations, and demographic and military characteristics of exertional hyponatremia cases among U.S. military members from 2004 through 2019.13

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2004 through 31 Dec. 2019. The surveillance population included all individuals who served in an active component of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at any time during the surveillance period. All data used to determine incident exertional hyponatremia diagnoses were derived from records routinely maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). These records document both ambulatory encounters and hospitalizations of active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces in fixed military and civilian (if reimbursed through the Military Health System [MHS]) treatment facilities worldwide. In-theater diagnoses of hyponatremia were identified from medical records of service members deployed to Southwest Asia/Middle East and whose health care encounters were documented in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS). TMDS records became available in the DMSS beginning in 2008.

For this analysis, a case of exertional hyponatremia was defined as 1) a hospitalization or ambulatory visit with a primary (first-listed) diagnosis of “hypo-osmolality and/or hyponatremia” (International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision [ICD-9]: 276.1; International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision [ICD-10]: E87.1) and no other illness or injury-specific diagnoses (ICD-9: 001–999) in any diagnostic position or 2) both a diagnosis of “hypo-osmolality and/or hyponatremia” (ICD-9: 276.1; ICD-10: E87.1) and at least 1 of the following within the first 3 diagnostic positions (dx1–dx3): “fluid overload” (ICD-9: 276.9; ICD-10: E87.70, E87.79), “alteration of consciousness” (ICD-9: 780.0*; ICD-10: R40.*), “convulsions” (ICD-9: 780.39; ICD-10: R56.9), “altered mental status” (ICD-9: 780.97; ICD-10: R41.82), “effects of heat/light” (ICD-9: 992.0–992.9; ICD-10: T67.0*–T67.9*), or “rhabdomyolysis” (ICD-9: 728.88; ICD-10: M62.82).13

Medical encounters were not considered case-defining events if the associated records included the following diagnoses in any diagnostic position: alcohol/illicit drug abuse; psychosis, depression, or other major mental disorders; endocrine (e.g., pituitary or adrenal) disorders; kidney diseases; intestinal infectious diseases; cancers; major traumatic injuries; or complications of medical care. Each individual could be considered an incident case of exertional hyponatremia only once per calendar year.

For surveillance purposes, a “recruit trainee” was defined as an active component member in an enlisted grade (E1–E4) who was assigned to 1 of the services’ recruit training locations (per the individual’s initial military personnel record). For this report, each service member was considered a recruit trainee for the period corresponding to the usual length of recruit training in his/her service. Recruit trainees were considered a separate category of enlisted service members in summaries of exertional hyponatremia by military grade overall.

In-theater diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia were analyzed separately using the same case-defining criteria and incidence rules that were applied to identify incident cases at fixed treatment facilities. Records of medical evacuations from the U.S. Central Command (CENTCOM) area of responsibility (AOR) (e.g., Iraq and Afghanistan) to a medical treatment facility outside the CENTCOM AOR were analyzed separately. Evacuations were considered case defining if the affected service members met the above criteria in a permanent military medical facility in the U.S. or Europe from 5 days before to 10 days after their evacuation dates.

The new electronic health record for the MHS, MHS GENESIS, was implemented at several military treatment facilities during 2017. Medical data from sites that are using MHS GENESIS are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Implementation of the second wave of MHS GENESIS sites began in 2019 and included 3 facilities in California (Travis Air Force Base [AFB], the Presidio of Monterey, and Naval Air Station Lemoore) and 1 in Idaho (Mountain Home AFB). Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities during 2017–2019 were not included in this analysis.

Results

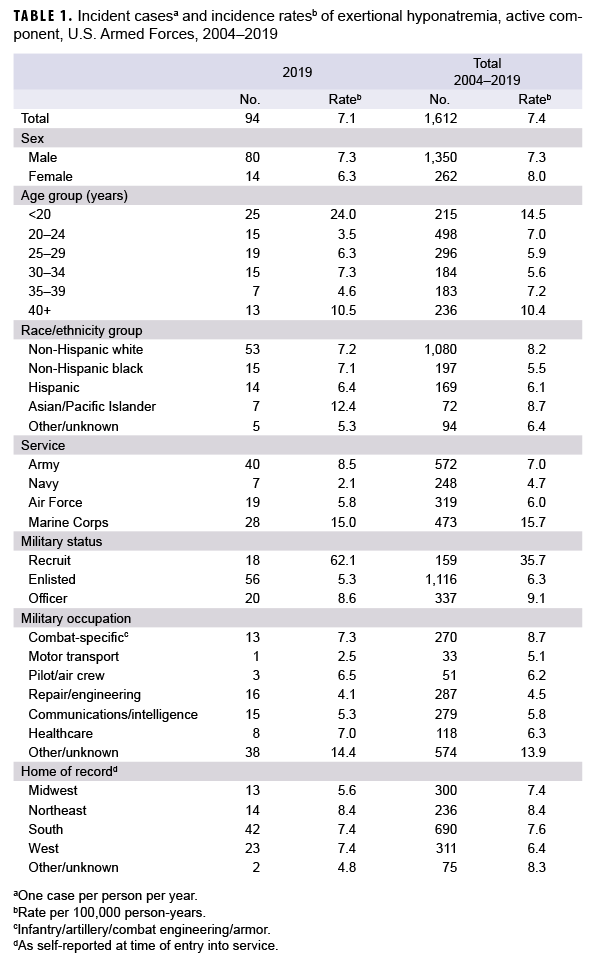

During 2004–2019, permanent medical facilities recorded 1,612 incident diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia among active component service members, for a crude overall incidence rate of 7.4 cases per 100,000 person-years (p-yrs) (Table 1). In 2019, there were 94 incident diagnoses of exertional hyponatremia (incidence rate: 7.1 per 100,000 p-yrs) among active component service members. During this year, males represented 85.1% of exertional hyponatremia cases (n=80); the annual incidence rate was slightly higher among males (7.3 per 100,000 p-yrs) than females (6.3 per 100,000 p-yrs) (Table 1).

The highest age group-specific incidence rates in 2019 were among the youngest (less than 20 years old) service members. Although the Army had the most cases during 2019 (n=40), the highest incidence rate was among members of the Marine Corps (15.0 per 100,000 p-yrs). In 2019, there were only 18 cases of exertional hyponatremia among recruit trainees, but their incidence rate was 7 times that of officers and more than 11 times that of other enlisted members (Table 1).

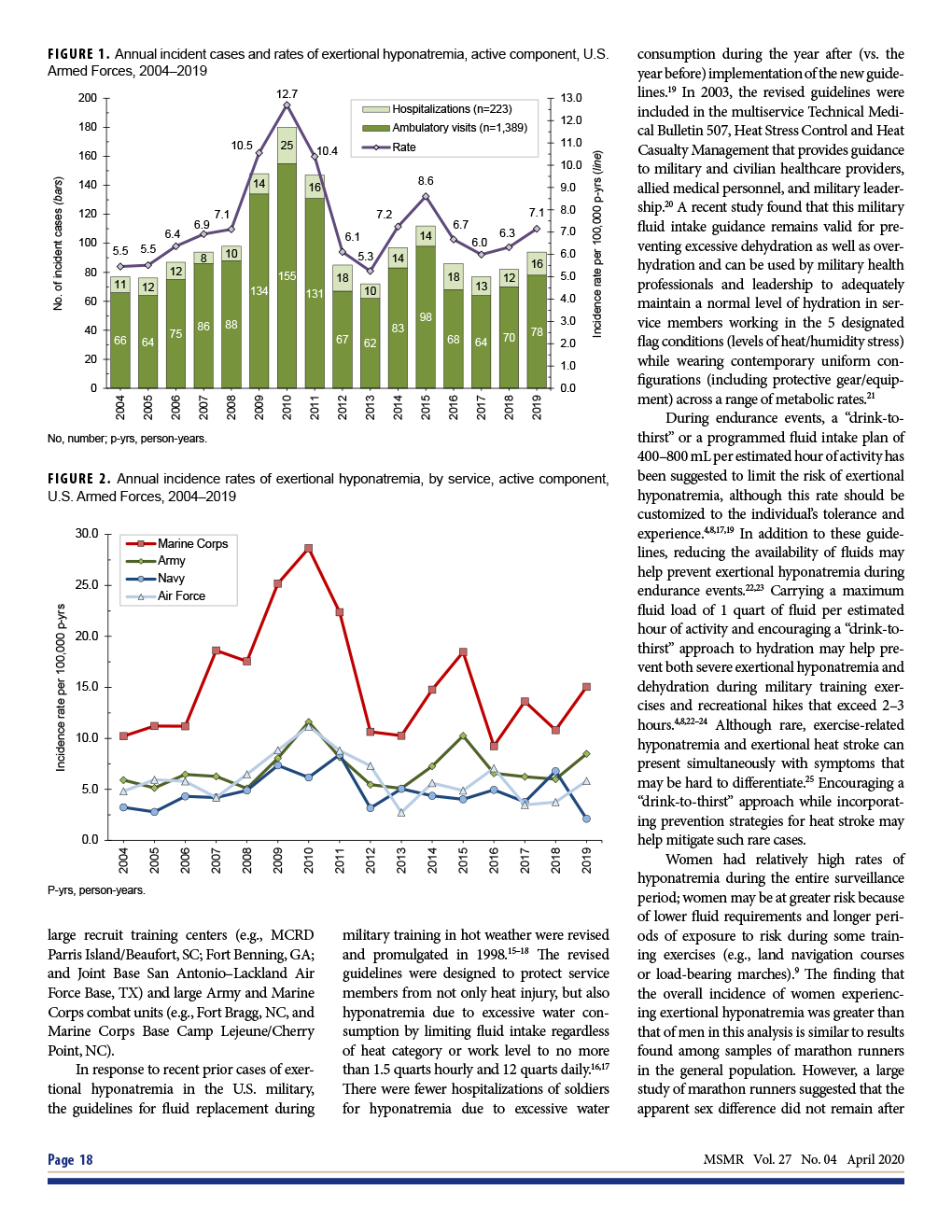

During the 16-year surveillance period, females had a slightly higher overall incidence rate of exertional hyponatremia diagnoses than males (Table 1). The overall incidence rate was highest in the Marine Corps (15.7 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest in the Navy (4.7 per 100,000 p-yrs). Overall rates during the surveillance period were highest among Asian/Pacific Islander (8.7 per 100,000 p-yrs) and non-Hispanic white service members (8.2 per 100,000 p-yrs) and lowest among non-Hispanic black service members (5.5 per 100,000 p-yrs). Although recruit trainees accounted for slightly less than one-tenth (9.9%) of all exertional hyponatremia cases, their overall crude incidence rate was 5.7 and 3.9 times the rates among other enlisted members and officers, respectively (Table 1). During the 16-year period, 86.2% (n=1,389) of all cases were diagnosed and treated without having to be hospitalized (Figure 1).

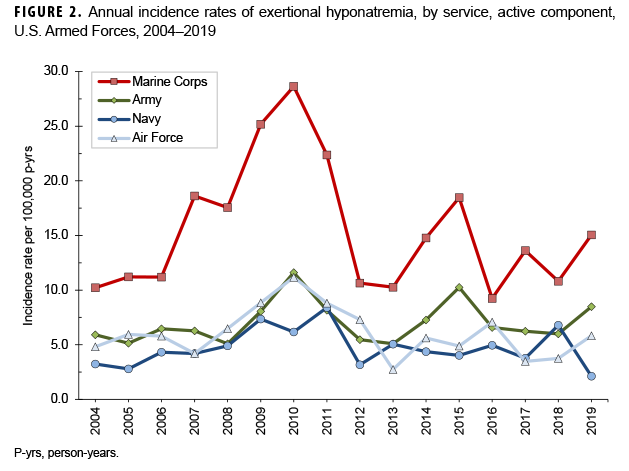

Between 2004 and 2019, crude annual rates of incident exertional hyponatremia diagnoses peaked in 2010 at 12.7 per 100,000 p-yrs and then decreased to a low of 5.3 cases per 100,000 p-yrs in 2013. The crude annual rates fluctuated between 2014 and 2019, reaching a high in 2015 (8.6 per 100,000 p-yrs) before decreasing through 2017. Crude annual rates rose again in 2018 and 2019, reaching 7.1 per 100,000 p-yrs in 2019 (Figure 1). During 2004–2019, annual incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia diagnoses were consistently higher in the Marine Corps compared to those in the other services, with the overall trend in rates primarily influenced by the trend among Marine Corps members (Figure 2). Between 2018 and 2019, annual incidence rates increased among Marine Corps, Army, and Air Force members and decreased among members of the Navy (Figure 2).

Exertional hyponatremia by location

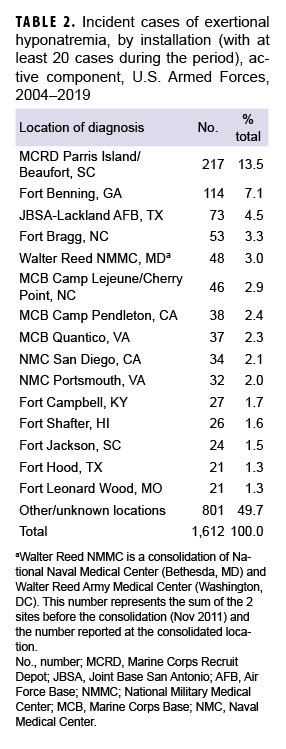

During the 16-year surveillance period, exertional hyponatremia cases were diagnosed at the medical treatment facilities of more than 150 U.S. military installations and geographic locations worldwide; however, 15 U.S. installations contributed 20 or more cases each and accounted for 50.3% of the total cases (Table 2). The installation with the most exertional hyponatremia cases overall was the Marine Corps Recruit Depot (MCRD) Parris Island/Beaufort, SC (n=217).

Exertional hyponatremia in Iraq and Afghanistan

From 2008 through 2019, a total of 18 cases of exertional hyponatremia were diagnosed and treated in Iraq and Afghanistan. No new cases were diagnosed in 2019. Deployed service members who were affected by exertional hyponatremia were most frequently male (n=16; 88.9%), non-Hispanic white (n=14; 77.8%), aged 20–24 years (n=8; 44.4%), in the Army (n=13; 72.2%), enlisted (n=15; 83.3%), and in combat-specific (n=7; 38.9%) or communications/intelligence (n=4; 22.2%) occupations (data not shown). During the entire surveillance period, 7 service members were medically evacuated from Iraq or Afghanistan for exertional hyponatremia (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

This report documents that after a period (2015–2017) of decreasing numbers and rates of exertional hyponatremia among active component U.S. military members, numbers and rates of diagnoses increased slightly in 2018 and 2019. Subgroup-specific patterns of overall incidence rates of exertional hyponatremia (e.g., sex, age, race/ethnicity, service, and military status) were generally similar to those reported in previous MSMR updates.14 It is important to note that in MSMR analyses before April 2018, in-theater cases were included if there was a diagnosis of hypo-osmolality and/or hyponatremia in any diagnostic position. Beginning in 2018, the same case-defining criteria that were applied to inpatient and outpatient encounters were applied to the in-theater encounters. Therefore, the results of the in-theater analysis are not comparable to those presented in earlier MSMR updates.

Several important limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this analysis. First, there is no diagnostic code specific for exertional hyponatremia. Thus, for surveillance purposes, cases of presumed exertional hyponatremia were ascertained from records of medical encounters that included diagnoses of hypo-osmolality and/or hyponatremia but not of other conditions (e.g., metabolic, renal, psychiatric, or iatrogenic disorders) that increase the risk of hyponatremia in the absence of physical exertion or heat stress. As such, exertional hyponatremia cases here likely include hyponatremia from both exercise- and non-exercise-related conditions. Consequently, the results of this analysis should be considered estimates of the actual incidence of symptomatic exertional hyponatremia from excessive water consumption among U.S. military members. In addition, the accuracy of estimated numbers, rates, trends, and correlates of risk depends on the completeness and accuracy of diagnoses that are documented in standardized records of relevant medical encounters. As a result, an increase in recorded diagnoses indicative of exertional hyponatremia may reflect, at least in part, increasing awareness of, concern regarding, and aggressive management of incipient cases by military supervisors and primary health care providers.

In the past, concerns about hyponatremia resulting from excessive water consumption were focused at training—particularly recruit training—installations. In this analysis, rates were relatively high among the youngest, and hence the most junior service members, and the highest numbers of cases tended to be diagnosed at medical facilities that support large recruit training centers (e.g., MCRD Parris Island/Beaufort, SC; Fort Benning, GA; and Joint Base San Antonio–Lackland Air Force Base, TX) and large Army and Marine Corps combat units (e.g., Fort Bragg, NC, and Marine Corps Base Camp Lejeune/Cherry Point, NC).

In response to recent prior cases of exertional hyponatremia in the U.S. military, the guidelines for fluid replacement during military training in hot weather were revised and promulgated in 1998.15–18 The revised guidelines were designed to protect service members from not only heat injury, but also hyponatremia due to excessive water consumption by limiting fluid intake regardless of heat category or work level to no more than 1.5 quarts hourly and 12 quarts daily.16,17 There were fewer hospitalizations of soldiers for hyponatremia due to excessive water consumption during the year after (vs. the year before) implementation of the new guidelines.19 In 2003, the revised guidelines were included in the multiservice Technical Medical Bulletin 507, Heat Stress Control and Heat Casualty Management that provides guidance to military and civilian health care providers, allied medical personnel, and military leadership.20 A recent study found that this military fluid intake guidance remains valid for preventing excessive dehydration as well as overhydration and can be used by military health professionals and leadership to adequately maintain a normal level of hydration in service members working in the 5 designated flag conditions (levels of heat/humidity stress) while wearing contemporary uniform configurations (including protective gear/equipment) across a range of metabolic rates.21

During endurance events, a “drink-to-thirst” or a programmed fluid intake plan of 400–800 mL per estimated hour of activity has been suggested to limit the risk of exertional hyponatremia, although this rate should be customized to the individual’s tolerance and experience.4,8,17,19 In addition to these guidelines, reducing the availability of fluids may help prevent exertional hyponatremia during endurance events.22,23 Carrying a maximum fluid load of 1 quart of fluid per estimated hour of activity and encouraging a “drink-tothirst” approach to hydration may help prevent both severe exertional hyponatremia and dehydration during military training exercises and recreational hikes that exceed 2–3 hours.4,8,22–24 Although rare, exercise-related hyponatremia and exertional heat stroke can present simultaneously with symptoms that may be hard to differentiate.25 Encouraging a “drink-to-thirst” approach while incorporating prevention strategies for heat stroke may help mitigate such rare cases.

Women had relatively high rates of hyponatremia during the entire surveillance period; women may be at greater risk because of lower fluid requirements and longer periods of exposure to risk during some training exercises (e.g., land navigation courses or load-bearing marches).9 The finding that the overall incidence of women experiencing exertional hyponatremia was greater than that of men in this analysis is similar to results found among samples of marathon runners in the general population. However, a large study of marathon runners suggested that the apparent sex difference did not remain after adjustment for body mass index and racing times.26–28

In many circumstances (e.g., recruit training and Ranger School), military trainees rigorously adhere to standardized training schedules regardless of weather conditions. In hot and humid weather, commanders, supervisors, instructors, and medical support staff must be aware of and enforce guidelines for work–rest cycles and water consumption. The finding in this report that most cases of hyponatremia were treated in outpatient settings suggests that monitoring by supervisors and medical personnel identified most cases during the early and less severe manifestations of hyponatremia.

In general, service members and their supervisors must be knowledgeable of the dangers of excessive water consumption as well as the prescribed limits for water intake during prolonged physical activity (e.g., field training exercises, personal fitness training, and recreational activities) in hot, humid weather. Military members (particularly recruit trainees and women) and their supervisors must be vigilant for early signs of heat-related illnesses and intervene immediately and appropriately (but not excessively) in such cases. Finally, the recent validation of the current fluid intake guidance highlights its importance as a resource to leadership in sustaining military readiness.

References

- Hew-Butler T, Rosner MH, Fowkes-Godek S, et al. Statement of the Third International Exercise-Associated Hyponatremia Consensus Development Conference, Carlsbad, California, 2015. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25(4):303–320.

- Montain SJ. Strategies to prevent hyponatremia during prolonged exercise. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7(4):S28–S35.

- Chorley J, Cianca J, Divine J. Risk factors for exercise-associated hyponatremia in non-elite marathon runners. Clin J Sport Med. 2007;17(6):471–477.

- 4Hew-Butler T, Loi V, Pani A, Rosner MH. Exercise-associated hyponatremia: 2017 update. Front Med (Lausanne). 2017;4:21.

- Edelman IS, Leibman J, O’Meara MP, Birkenfeld LW. Interrelations between serum sodium concentration, serum osmolarity and total exchangeable sodium, total exchangeable potassium and total body water. J Clin Invest. 1958;37(9):1236–1256.

- Nguyen MK, Kurtz I. Determinants of plasma water sodium concentration as reflected in the Edelman equation: role of osmotic and Gibbs-Donnan equilibrium. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol. 2004;286(5):F828–F837.

- Noakes TD, Sharwood K, Speedy D, et al. Three independent biological mechanisms cause exercise-associated hyponatremia: evidence from 2,135 weighed competitive athletic performances. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(51):18550–18555.

- Oh RC, Malave B, Chaltry JD. Collapse in the heat—from overhydration to the emergency room—three cases of exercise-associated hyponatremia associated with exertional heat illness. Mil Med. 2018;183(3–4):e225–e228.

- Carter R III. Exertional heat illness and hyponatremia: an epidemiological prospective. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2008;7(4):S20–S27.

- Buono MJ, Ball KD, Kolkhorst FW. Sodium ion concentration vs. sweat rate relationship in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2007;103(3):990–994.

- Buono MJ, Sjoholm NT. Effect of physical training on peripheral sweat production. J Appl Physiol (1985). 1988;65(2):811–814.

- Nadel ER, Pandolf KB, Roberts MF, Stolwijk JA. Mechanisms of thermal acclimation to exercise and heat. J Appl Physiol. 1974;37(4):515–520.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Surveillance Case Definition. Hyponatremia. March 2017. https://health.mil/Military-Health-Topics/Combat-Support/Armed-Forces-Health-Surveillance-Branch/Epidemiology-and-Analysis/Surveillance-Case-Definitions. Accessed 23 March 2020.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Update: Exertional hyponatremia, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2003–2018. MSMR. 2019;26(3):27–31.

- Army Medical Surveillance Activity. Case reports: Hyponatremia associated with heat stress and excessive water consumption: Fort Benning, GA; Fort Leonard Wood, MO; Fort Jackson, SC, June–Aug. 1997. MSMR. 1997;3(6):2–3,8.

- Department of the Army, Office of the Surgeon General. Memorandum. Policy guidance for fluid replacement during training, dated 29 April 1998.

- Montain S., Latzka WA, Sawka MN. Fluid replacement recommendations for training in hot weather. Mil Med. 1999;164(7):502–508.

- O’Brien KK, Montain SJ, Corr WP, Sawka MN, Knapik JJ, Craig SC. Hyponatremia associated with overhydration in U.S. Army trainees. Mil Med. 2001;166(5):405–410.

- Army Medical Surveillance Activity. Surveillance trends: Hyponatremia associated with heat stress and excessive water consumption: the impact of education and a new Army fluid replacement policy. MSMR. 1999;5(2):2–3,8–9.

- Headquarters, Department of the Army and Air Force. Technical Bulletin, Medical 507, Air Force Pamphlet, 48–152. Heat Stress Control and Heat Casualty Management. 7 March 2003.

- Luippold AJ, Charkoudian N, Kenefick RW, et al. Update: Efficacy of military fluid intake guidelines. Mil Med. 2018;183(9/10):e338–e342.

- Hew-Butler T, Verbalis JG, Noakes TD. Updated fluid recommendation: Position statement from the International Marathon Medical Directors Association (IMMDA). Clin J Sport Med. 2006;16(4):283–292.

- Thomas DT, Erdman KA, Burke LM. American College of Sports Medicine Joint Position Statement. Nutrition and athletic performance. Med Sci Sport Exerc. 2016;48(3):543–568.

- Nolte HW, Nolte K, Hew-Butler T. Ad libitum water consumption prevents exercise-associated hyponatremia and protects against dehydrations in soldiers performing a 40-km route-march. Mil Med Res. 2019;6(1):1.

- Oh RC, Galer M, Bursey MM. Found in the field—a soldier with heat stroke, exercise-associated hyponatremia, and kidney injury. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2018;17(4):123–125.

- Almond CS, Shin AY, Fortescue EB, et al. Hyponatremia among runners in the Boston Marathon. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(15):1550–1556.

- Ayus JC, Varon J, Arieff AI. Hyponatremia, cerebral edema, and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema in marathon runners. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132(9):711–714.

- Hew TD, Chorley JN, Cianca JC, Divine JG. The incidence, risk factors, and clinical manifestations of hyponatremia in marathon runners. Clin J Sport Med. 2003;13(1):41–47.