What Are the New Findings?

The incidence of chlamydia and gonorrhea generally increased among male and female service members in the latter half of the surveillance period; however, the rates decreased in 2020. The incidence of genital HPV and HSV continued to decrease. The incidence of syphilis decreased among male and female service members in 2020.

What is the Impact on Readiness and Force Health Protection?

STIs can adversely impact service members’ availability and ability to perform their duties and can result in serious medical sequelae if untreated. Establishing standards for screening, testing, treatment, and reporting would likely improve efforts to detect STI-related health threats. Continued behavioral risk-reduction interventions are needed to counter STIs among military service members.

Abstract

This report summarizes incidence rates of the 5 most common sexually transmitted infections (STIs) among active component service members of the U.S. Armed Forces during 2012–2020. Infections with chlamydia were the most common, followed in decreasing order of frequency by infections with genital human papillomavirus (HPV), gonorrhea, genital herpes simplex virus (HSV), and syphilis. Compared to males, females had higher rates of all STIs except for syphilis. In general, compared to their respective counterparts, younger service members, non-Hispanic Blacks, soldiers, and enlisted members had higher incidence rates of STIs. Although rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea increased among both male and female service members during the latter half of the surveillance period, there was a notable decrease in the rates of chlamydia in both sexes from 2019 through 2020, and the rates of gonorrhea decreased slightly for both males and females during 2018–2020. Rates of syphilis increased among male service members through 2018 but decreased during 2019–2020; the rate among female service members increased between 2012 and 2014, generally leveled off through 2018, increased in 2019, and then decreased in 2020. Rates of genital HSV declined during the period from 2016 through 2020 for both male and female service members. The rates of genital HPV decreased steadily between 2012 and 2020 in males and declined between 2015 and 2020 among females. Similarities to and differences from the findings of the last MSMR update on STIs are discussed.

Background

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are relevant to the U.S. military because of their relatively high incidence, adverse impact on service members' availability and ability to perform their duties, and potential for serious medical sequelae if untreated.1 Two of the most common bacterial STIs are caused by Chlamydia trachomatis (chlamydia) and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea). Rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea have been steadily increasing in the general U.S. population among both males and females since 2000.2 A March 2020 MSMR report documented more than 221,000 incident infections of chlamydia and more than 34,000 incident infections of gonorrhea among active component U.S. military members between 2011 and 2019, with increasing incidence rates of these conditions among both males and females in the latter half of the surveillance period, mirroring trends in the general U.S. population.3

Another important bacterial STI is syphilis, which is caused by the bacterium Treponema pallidum. Rates of primary and secondary syphilis in the U.S. have risen steadily from a historic low in 2001 and increased 71.4% from 6.3 cases per 100,000 persons in 2014 to 10.8 cases per 100,000 persons in 2018.2 This upward trend is mirrored in the active component of the U.S. Armed Forces, in which the incidence of syphilis (of any type) increased steadily between 2011 and 2018, with most of the increase after 2014 occurring among males.3 Although these 3 relatively common bacterial STIs are curable with antibiotics, there is continued concern regarding the threat of multidrug resistance.4–6

Common viral STIs in the U.S. include infections caused by human papillomavirus (HPV) and genital herpes simplex virus (HSV). HPVs are DNA viruses that infect basal epithelial (skin or mucosal) cells. HPV genotypes 6 and 11 are responsible for 90% of all genital wart infections,7 while genotypes 16 and 18 cause most HPV-related cancers.8 HSV can cause genital or oral herpes infections that are characterized by the appearance of 1 or more vesicles that can break and leave painful ulcers. Most genital herpes infections are caused by type 2 (HSV-2); however, type 1 (HSV-1), which is most often associated with oral herpes infection, is estimated to be responsible for 50% of new genital herpes infections.9 Neither HPV nor HSV viral infections are curable with antibiotics; however, suppression of recurrent herpes manifestations is attainable using antiviral medication, and there is a vaccine to prevent infection with 4 of the most common HPV serotypes as well as 5 additional cancer-causing types.7 From 2011 through 2019, the overall incidence rates of genital HPV and HSV in the active component were 56.4 and 23.3 cases per 10,000 person-years (p-yrs), respectively.3

The current analysis updates the findings of previous MSMR articles on STIs among active component service members.1,3 Specifically, this report summarizes incident cases and incidence rates of 5 of the most common STIs during 2012–2020 and describes their distributions by demographic and military characteristics.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 Jan. 2012 through 31 Dec. 2020. The surveillance population consisted of all active component service members of the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps who served at any time during the period. Diagnoses of STIs were ascertained from medical administrative data and reports of notifiable medical events routinely provided to the Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division (AFHSD) and maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS) for surveillance purposes. STI cases were also derived from positive laboratory test results recorded in the Health Level 7 (HL7) chemistry and microbiology databases maintained by the Navy and Marine Corps Public Health Center at the EpiData Center.

For each service member, the number of months in active military service was ascertained and then aggregated into a total for all service members during each calendar year. The resultant annual totals were expressed as person-years of service and used as the denominators for the calculation of annual incidence rates. Person time that was not considered to be time at risk for each STI was excluded (i.e., the 30 days following each incident chlamydia or gonorrhea infection and all person-time following the first diagnosis, medical event report, or positive laboratory test of HSV, HPV, or syphilis).

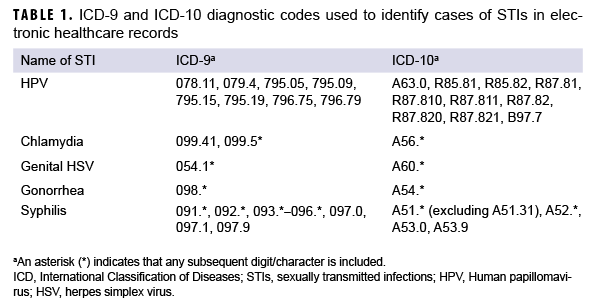

An incident case of chlamydia was defined by any of the following: 1) a case defining diagnosis (Table 1) in the first or second diagnostic position of a record of an outpatient or in-theater medical encounter, 2) a confirmed notifiable disease report for chlamydia, or 3) a positive laboratory test for chlamydia (any specimen source or test type). An incident case of gonorrhea was similarly defined by 1) a case-defining diagnosis in the first or second diagnostic position of a record of an inpatient or outpatient or in-theater encounter, 2) a confirmed notifiable disease report for gonorrhea, or 3) a positive laboratory test for gonorrhea (any specimen source or test type). For both chlamydia and gonorrhea, an individual could be counted as having a subsequent case only if there were more than 30 days between the dates on which the case-defining diagnoses were recorded.

Incident cases of HSV were identified by 1) the presence of the requisite International Classification of Diseases, 9th or 10th Revision (ICD-9 or ICD-10, respectively) codes in either the first or second diagnostic positions of a record of an outpatient or in-theater encounter or 2) a positive laboratory test from a genital specimen source. Antibody tests were excluded because they do not allow for distinction between genital and oral infections. Incident cases of HPV were similarly identified by 1) the presence of the requisite ICD-9 or ICD-10 codes in either the first or second diagnostic positions of a record of an outpatient or in-theater encounter or 2) a positive laboratory test from any specimen source or test type. Outpatient encounters for HPV with evidence of an immunization for HPV within 7 days before or after the encounter date were excluded, as were outpatient encounters with a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code indicating HPV vaccination, as such encounters were potentially related to the vaccination administration. An individual could be counted as an incident case of HSV or HPV only once during the surveillance period. Individuals who had diagnoses of HSV or HPV infection before the surveillance period were excluded from the analysis.

An incident case of syphilis was defined by 1) a qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 code in the first, second, or third diagnostic position of a hospitalization, 2) at least 2 outpatient or in-theater encounters within 30 days of each other with a qualifying ICD-9 or ICD-10 code in the first or second position, 3) a confirmed notifiable disease report for any type of syphilis, or 4) a record of a positive polymerase chain reaction or treponemal laboratory test. Stages of syphilis (primary, secondary, late, latent) could not be distinguished because the HL7 laboratory data do not allow for differentiation of stages and because there is a high degree of misclassification associated with the use of ICD diagnosis codes for stage determination.10,11 An individual could be considered an incident case of syphilis only once during the surveillance period; those with evidence of prior syphilis infection were excluded from the analysis.

Results

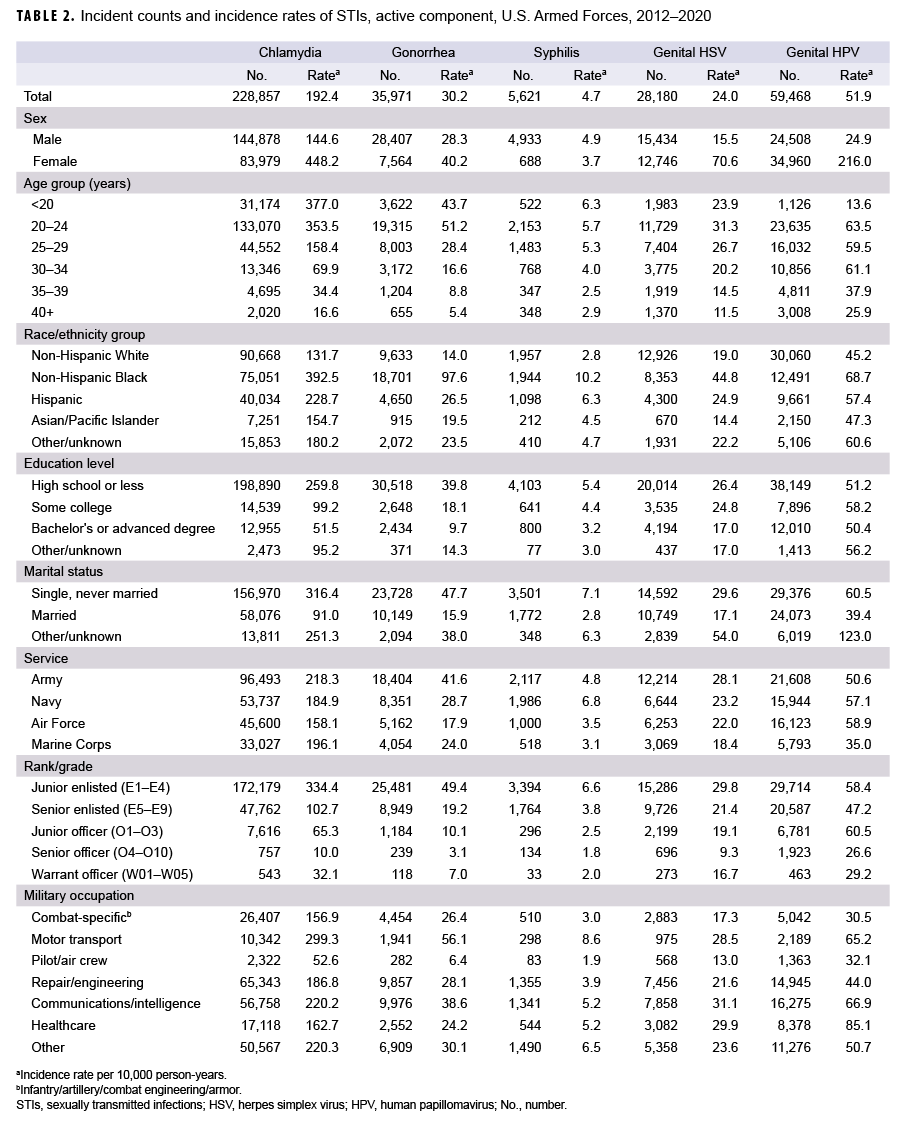

Between 2012 and 2020, the number of incident chlamydia infections among active component service members was greater than the sum of the other 4 STIs combined and 3.8 times the total number of genital HPV infections—the next most frequently identified STI during this period (Table 2). With the exception of syphilis, the crude overall incidence rates of all STIs were markedly higher among female service members than male service members. For chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis, overall incidence rates were highest among those aged 24 years or younger and decreased with advancing age. However, overall rates of genital HSV and HPV infections were highest among those aged 20–24 years. Overall rates of all STIs were highest among non-Hispanic Black service members compared to those in other race/ethnicity groups. For chlamydia, gonorrhea, and genital HSV infections, overall rates were highest among members of the Army. The overall incidence rate of syphilis was highest among Navy members, and the overall rate of genital HPV infections was highest among Air Force members.

Compared to their respective counterparts, enlisted service members and those with lower levels of educational achievement tended to have higher overall rates of all STIs. Married service members had the lowest overall incidence rates of all 5 STIs compared to service members who were single and never married or those of other/ unknown marital status. Overall rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis were highest among those working in motor transport occupations. In contrast, overall genital HPV infection rates were highest among those in healthcare occupations, and the highest rates of genital HSV infections were among those working in communications/ intelligence, health care, or motor transport (Table 2). Patterns of incidence rates over time for each specific STI are described in the subsections below.

Chlamydia

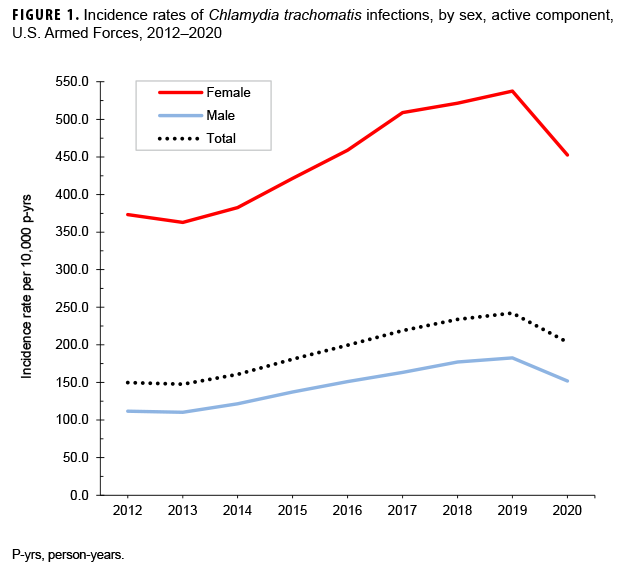

During the surveillance period, annual incidence rates of chlamydia among female service members were generally 3 times the rates among male service members. Annual rates among all active component members increased 64.0% between 2013 and 2019, with rates among both females and males peaking in 2019 (537.5 per 10,000 p-yrs and 182.7 per 10,000 p-yrs, respectively) (Figure 1). In both sexes, this increase was primarily attributed to service members in the youngest age groups (less than 25 years among females; less than 30 years among males) (data not shown).

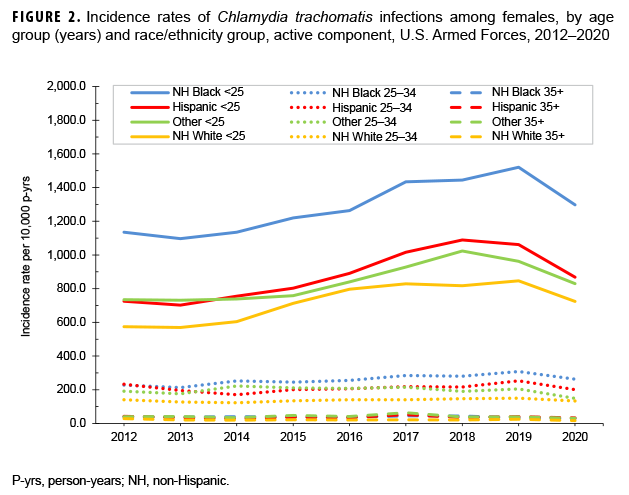

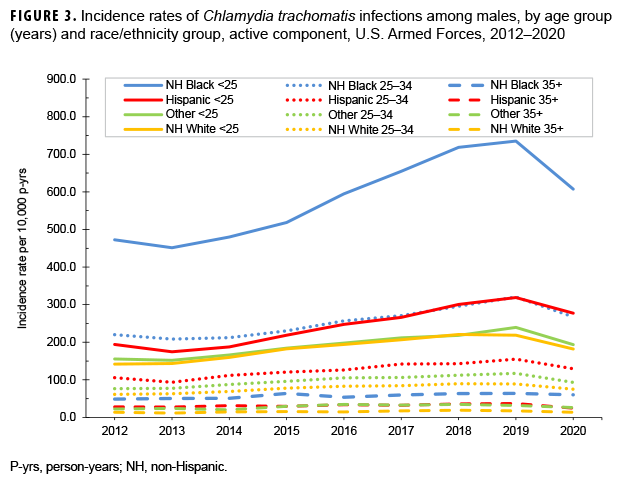

Among female service members in each race/ethnicity group, annual rates of chlamydia generally increased among those under 25 years old during 2013–2018 (Figure 2). Among non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White female service members in this age group, annual rates of chlamydia increased between 2018 and 2019; in contrast, annual rates among Hispanic female service members and female service members of other/unknown race/ethnicity decreased from 2018 through 2019. Then, between 2019 and 2020, annual rates decreased among female service members under 25 years old in all race/ethnicity groups. Rates remained relatively stable among female service members aged 25–34 years and among those aged 35 years or older (Figure 2). Among male service members, annual rates of chlamydia increased consistently between 2013 and 2019 in all age and race/ethnicity groups under 35 years old, with the exception of non-Hispanic Whites. Among non-Hispanic White male service members under 35 years old, annual rates of chlamydia leveled off between 2018 and 2019. During 2013–2019, annual rates remained relatively stable among male service members aged 35 or older (Figure 3). Between 2019 and 2020, rates decreased among male service members in all age and race/ethnicity groups, with the most pronounced decline among non-Hispanic Black male service members under 25 years old (Figure 3).

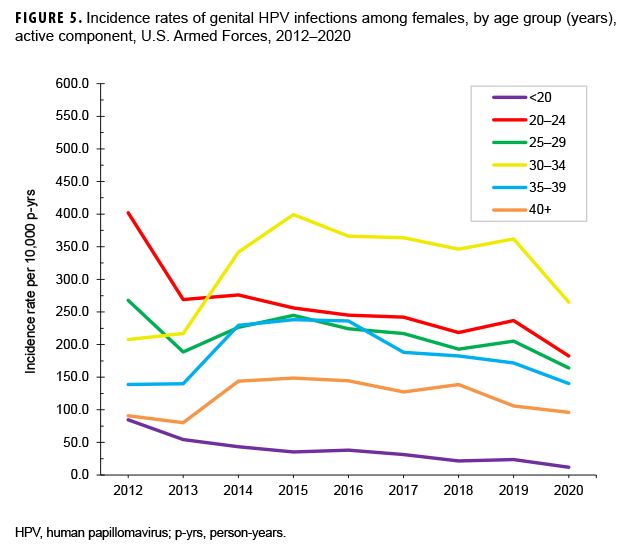

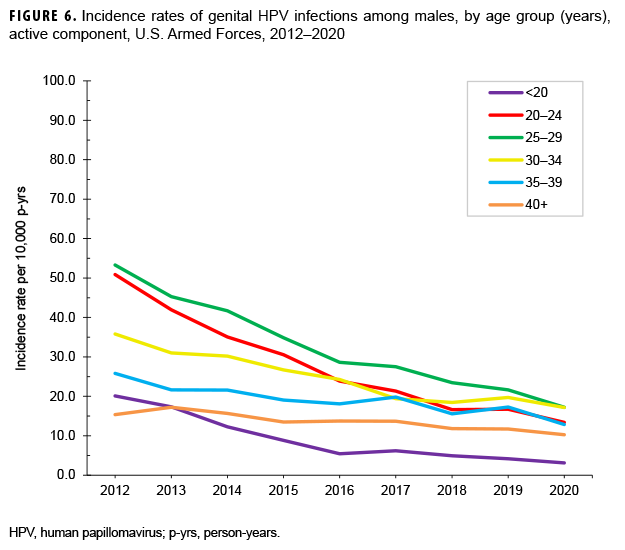

Genital HPV

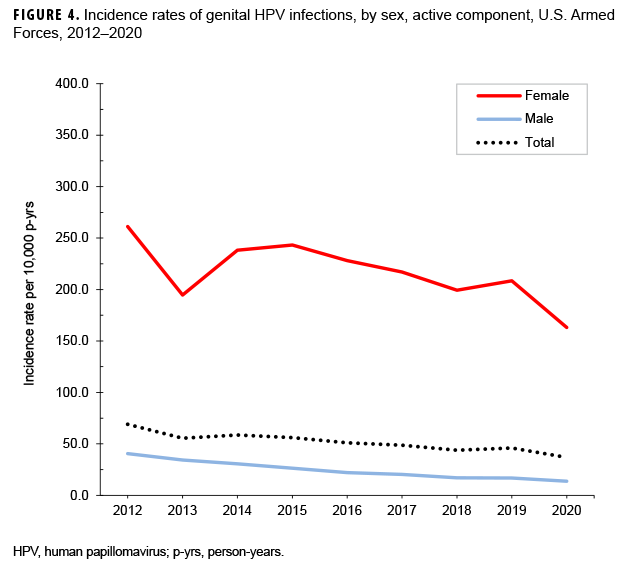

The crude annual incidence rates of genital HPV infections decreased 46.6% among all active component service members from the beginning to the end of the surveillance period, with the most marked decrease occurring among females (Figure 4). There was a slight dip in the overall incidence of genital HPV infections among all active component service members in 2013 at 55.6 cases per 10,000 p-yrs, but the lowest point was reached in 2020 at 36.9 cases per 10,000 p-yrs. Incidence rates of genital HPV infections among female service members declined by 37.5% during the surveillance period, from a high of 261.2 cases per 10,000 p-yrs in 2012 to a low of 163.1 cases per 10,000 p-yrs in 2020 (Figure 4). Rates among male service members decreased, from 40.6 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2012 to 16.9 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2019 (66.1%). Between 2015 and 2020, annual rates of genital HPV infections decreased among female service members in all age groups (Figure 5). The decrease in the genital HPV infection rates among male service members overall during 2012–2020 was driven mainly by decreases in the rates in those aged 20–29 years (Figure 6).

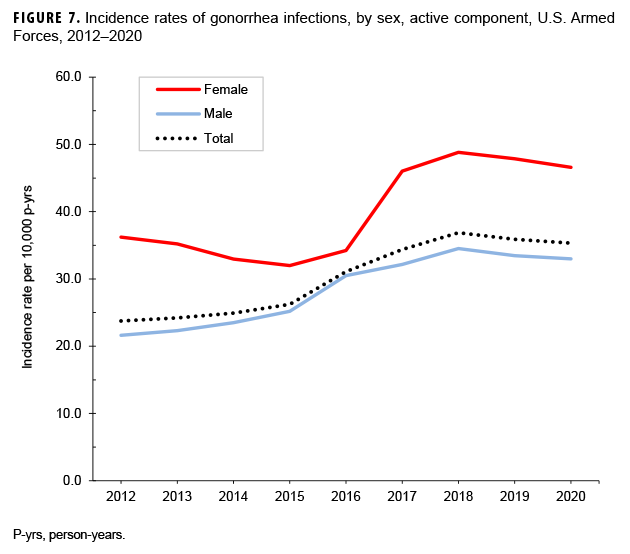

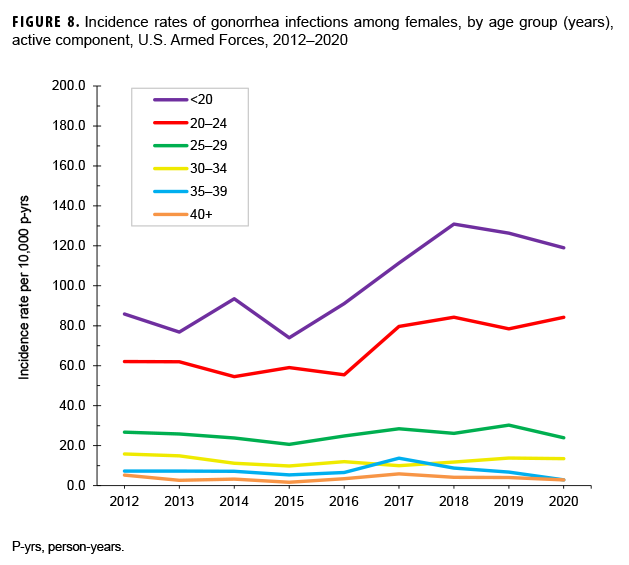

Gonorrhea

Between 2012 and 2020, the crude annual incidence rate of gonorrhea increased by 48.7%; however, after increasing steadily from 2012 through 2018, the rate decreased slightly in 2019 and 2020 (Figure 7). The annual rates among female service members declined between 2012 and 2015 then increased through 2018 before decreasing slightly in 2019 and 2020. After increasing steadily between 2012 and 2018, the rate among male service members also decreased slightly through 2020 (Figure 7). These trends in gonorrhea incidence were primarily driven by similar trends among females under age 25 years old and among males under age 30 years old (Figures 8, 9). The annual rates of gonorrhea increased during the surveillance period among all race/ethnicity groups through 2018, but then fell slightly in 2019 and 2020 for all groups except non-Hispanic Black service members and Asian-Pacific Islander service members. Among non-Hispanic Black service members, rates continued to increase in 2019 and 2020. For Asian-Pacific Islander service members, the rate dropped in 2018 but then leveled off in 2020 (data not shown).

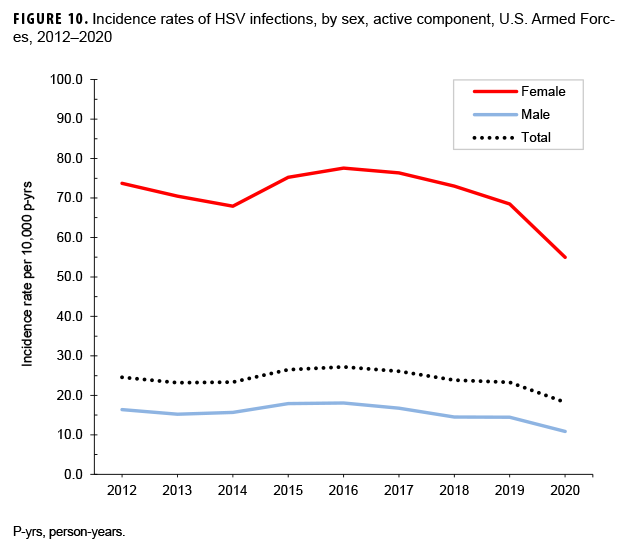

Genital HSV

Crude annual incidence rates of genital HSV infections decreased from 24.6 to 18.2 per 10,000 p-yrs over the course of the surveillance period. Rates among female service members ranged from a high of 77.6 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2016 to a low of 55.0 per 10,000 p-yrs in 2020. The rates for male service members were also highest in 2016 (18.1 per 10,000 p-yrs) and reached the lowest point in 2020 (10.9 per 10,000 p-yrs) (Figure 10). Over the course of the surveillance period, the incidence rates of genital HSV infections decreased among service members in all age groups (data not shown). The rates decreased between 2018 and 2020 among females in all age groups except for those aged 35–39 years, among whom rates leveled off during 2019–2020. Annual rates decreased among males in all age groups during 2019–2020 (data not shown). In addition, the incidence rates decreased among all race/ethnicity groups from 2017 through 2020 (data not shown).

Syphilis

The crude incidence rate for syphilis in the last year of the surveillance period (5.2 per 10,000 p-yrs) was 2.2 times that observed in 2012 (2.4 per 10,000 p-yrs), with the increase primarily driven by cases identified among male service members (Figure 11). Rates of syphilis steadily increased among males until 2018, after which rates decreased through 2020. Among females, rates increased between 2012 and 2014, generally leveled off through 2018, increased in 2019, and then decreased in 2020. The overall incidence rates of syphilis generally decreased with advancing age among both sexes (data not shown). Among males, this pattern of decreasing overall incidence with increasing age was consistent among all race/ethnicity groups; there were not enough cases to evaluate associations between age and race/ethnicity group among females (data not shown).

Editorial Comment

As in previous reports, the crude annual incidence rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis generally increased during the surveillance period. However, from 2019 through 2020, the rates of chlamydia and syphilis infections decreased in service members of both sexes. Between 2018 and 2020, the rates of gonorrhea decreased slightly in both males and females. In contrast, the decline in incidence rates of genital HSV spanned the period from 2016 through 2020 for both male and female service members. The rates of genital HPV decreased steadily between 2012 and 2020 in males and declined between 2015 and 2020 among females. Overall incidence rates of STIs were higher among females compared to males for HPV, HSV, gonorrhea, and chlamydia. Syphilis was the only STI in this analysis for which the incidence was, on average, higher among male compared to female service members.

Higher incidence rates of most STIs among females compared to males can likely be attributed to implementation of the services’ screening programs for STIs among female service members as they enter active service and during the subsequent annual screenings for females younger than 26 years old. Because asymptomatic infection with chlamydia, gonorrhea, or HPV is common among sexually active females, widespread screening may result in sustained high numbers of infections diagnosed among young females. Although rates of chlamydia and gonorrhea increased among both male and female service members during the latter half of the surveillance period, mirroring the increasing rates in the civilian population,2 there was a notable decrease in service members’ rates of chlamydia in both sexes from 2019 through 2020, and the rates of gonorrhea decreased slightly for both males and females during 2019 and 2020. In the U.S., rates of chlamydia have been increasing among both males and females since 2000, and rates of gonorrhea have been increasing among both sexes since 2013.2 The increases seen through 2018 in both the civilian and military populations could reflect true increases in the incidence of infections as well as improved screening coverage in males, particularly extragenital screening in males who have sex with males.12 Analyses of provisional data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) National Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (NNDDS) for the first 40 weeks of 2019 and 2020 revealed that, at week 40 of 2020, the cumulative year-to-date count of chlamydia cases was down 18% relative to the cumulative count at that time in 2019.13 A smaller decrease (7%) was observed in the cumulative count of syphilis (primary and secondary) cases at week 40 in 2020 compared with week 40 in 2019.13 No significant reduction was seen for gonorrhea.13 A similar pattern was observed among active component service members in the current study. The incidence of chlamydia decreased by 16% between 2019 and 2020, and the incidence of gonorrhea remained relatively stable between 2019 and 2020. The decreases in civilian case counts have so far been attributed mostly to COVID-19 pandemic-related declines in the testing and/ or reporting of cases,14 and it is possible that the COVID-19 pandemic had a similar effect on the military health system. It is important to note, however, that national civilian data for both 2019 and 2020 were preliminary at the time of this report.

No data on sexual risk behaviors were available for this study, but prior surveys of military personnel have indicated high levels of sexual risk behaviors. The 2015 Department of Defense Health Related Behaviors Survey (HRBS) documented that 19.4% of respondents reported having more than 1 sex partner in the past year and that 36.7% reported sex with a new partner in the past year without using a condom; these percentages were almost double those reported from the previous survey in 2011.15 Data from the 2018 HRBS were not available at the time of this report, precluding any comparisons.

The general downward trend in incidence rates of genital HPV infections observed during the surveillance period may be related to the introduction of the HPV vaccine for adult and young females in 2006 and for males in 2010. Among civilian females aged 14–24 years, cervical/ vaginal prevalence of HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18 decreased by approximately 6% from the period 2003–2006 to 2009–2012.16 The HPV vaccine is currently not a mandatory vaccine for military service, but it is encouraged and offered to service members. Because the HPV vaccine (Gardasil) is approved for use among males and females beginning at age 9, it is possible that an increasing number of members who entered military service during the surveillance period may have been vaccinated for HPV before entering service. This prior vaccination may account for the decrease in the annual rates of genital HPV infections during the surveillance period.

The trends in the incidence of HSV and syphilis in the U.S. military are also similar to what is observed in the civilian population. Data from the CDC’s National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey indicate that the seroprevalence of both HSV-1 and HSV-2 has decreased in the U.S. population since 1999. 2

In contrast, the incidence of primary and secondary syphilis reported to the CDC has increased markedly since 2001, with males accounting for the majority of cases.2,17

This report has several limitations that should be considered when interpreting the results. First, diagnoses of STIs may be incorrectly coded. For example, STI-specific “rule out” diagnoses or vaccinations (e.g., HPV vaccination) may be reported with STI-specific diagnostic codes, which would result in an overestimate of STI incidence. Cases of syphilis, genital HSV, and genital HPV infections based solely on laboratory test results are considered “suspect” because the laboratory test results cannot distinguish between acute and chronic infections. However, because incident cases of these STIs were identified based on the first qualifying encounter or laboratory result, the likelihood is high that most such cases are acute and not chronic.

STI cases may not be captured if coded in the medical record using symptom codes (e.g., urethritis) rather than STI-specific codes. In addition, the counts of STI diagnoses reported here may underestimate the actual numbers of diagnoses because some affected service members may be diagnosed and treated through non-reimbursed, nonmilitary care providers (e.g., county health departments or family planning centers) or in deployed settings (e.g., overseas training exercises, combat operations, or aboard ships). Laboratory tests that are performed in a Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care setting, a shipboard facility, a battalion aid station, or an in theater facility were not captured in the current analysis. Finally, medical data from sites that were using the new electronic health record for the Military Health System, MHS GENESIS, between July 2017 and October 2019 are not available in the DMSS. These sites include Naval Hospital Oak Harbor, Naval Hospital Bremerton, Air Force Medical Services Fairchild, and Madigan Army Medical Center. Therefore, medical encounter data for individuals seeking care at any of these facilities from July 2017 through Oct. 2019 were not included in the current analysis.

For some STIs, the detection of prevalent infections may occur long after the time of initial infections. As a result, changes in incidence rates may reflect, at least in part, temporal changes in case ascertainment, such as a shift to more aggressive screening. The lack of standard practices across the services and their installations regarding screening, testing, treatment, and reporting complicate interpretations of differences between services, military and demographic subgroups, and locations. Establishing screening, testing, treatment, and reporting standards across the services and ensuring adherence to such standards would likely improve efforts to detect and characterize STI-related health threats. In addition, continued behavioral risk-reduction interventions are needed to counter STIs among military service members.

References

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Sexually transmitted infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2000–2012. MSMR. 2013;20(2):5–10.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted disease surveillance 2018. Accessed 22 February 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/default.htm.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Sexually transmitted infections, active component, U.S. Armed Forces, 2011–2019. MSMR. 2020;27(3):2–11.

- Krupp K, Madhivanan P. Antibiotic resistance in prevalent bacterial and protozoan sexually transmitted infections. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS2015;36(1):3–8.

- Growing antibiotic resistance forces updates to recommended treatment for sexually transmitted infections [news release]. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 30 August 2016. Accessed 23 February 2021. https://www.who.int/ news-room/detail/30-08-2016-growing-antibioticresistance-forces-updates-to-recommended-treatment-for-sexually-transmitted-infections.

- Tien V, Punjabi C, Holubar MK. Antimicrobial resistance in sexually transmitted infections. J Travel Med. 2020;27(1):1–11.

- National Cancer Institute. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccines. Accessed 23 February 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causesprevention/risk/infectious-agents/hpv-vaccine-factsheet.

- National Cancer Institute. HPV and cancer. Accessed 19 February 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/causes-prevention/risk/infectiousagents/hpv-fact-sheet

- Roberts CM, Pfister JR, Spear SJ. Increasing proportion of herpes simplex virus type 1 as a cause of genital herpes infection in college students. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(10):797–800.

- Garges E, Stahlman S, Jordan N, Clark LL. P3.69 Administrative medical encounter data and medical event reports for syphilis surveillance: a cautionary tale. Sex Transm Infect. 2017;93(suppl 2):A118.

- Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch. Use of ICD-10 code A51.31 (condyloma latum) for identifying cases of secondary syphilis. MSMR. 2017;24(9):23.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance. National Overview of STDs, 2018: Chlamydia. Accessed 23 February 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/chlamydia.htm.

- Crane MA, Popovic A, Stolbach AI, Ghanem KG. Reporting of sexually transmitted infections during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sex Transm Infect. 2021;97(2):101–102.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention. NCHHSTP Newsroom. 2020 Releases. 2020 STD Prevention Conference Roundtable Discussion. Accessed 1 March 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/newsroom/2020/2020-std-prevention-conference.html.

- Meadows SO, Engel CO, Collins RL, et al. 2015 Health Related Behaviors Survey. Sexual Behavior and Health among Active-Duty Service Members. RAND Corporation Research Brief. Accessed 19 February 2021. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_briefs/RB9955z5.html.

- HPV Infections Targeted by Vaccine Decrease in U.S. [news release]. Bethesda, MD; National Cancer Institute; 9 March 2016. Accessed 24 Feb. 2021. https://www.cancer.gov/newsevents/cancer-currents-blog/2016/hpv-infectionsdecreased.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018 Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance. National Profile Overview: Syphilis. Accessed 24 Feb. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats18/Syphilis.htm.