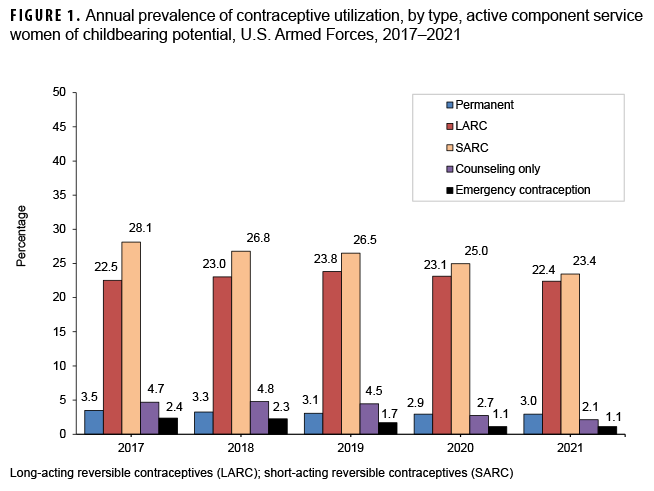

This report summarizes the annual prevalence of permanent sterilization, as well as use of long- and short-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs and SARCs, respectively), contraceptive counseling services, and use of emergency contraceptives from 2017 through 2021 among active component U.S. service women. In 2021, almost half (n=115,671, 45.8%) of women used either LARCs or SARCs. From 2017 to 2021, permanent sterilization decreased from 3.5% to 3.0%; LARC use increased to 23.8% in 2019 and then decreased to 22.4% by 2021; SARC use decreased from 28.1% to 23.4%; and emergency contraceptive use decreased from 2.4% to 1.1%. Annual prevalence of contraceptive counseling only decreased from 4.7% to 2.1%. These data demonstrate that a large proportion of service women utilize at least one form of contraception, and SARCs and LARCs remain the two most popular options.

What are the new findings?

Use of both long- and short-acting reversible contraception has decreased in recent years among active component service women. However, they remain among the most popular forms of contraception, with 23.4% and 22.4% using short- and long-active reversible contraception in 2021, respectively.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Knowledge of, access to, and consistent use of contraception is key for active component service member readiness, both for preventing pregnancy and promoting menstrual suppression. Long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) is an effective method for reducing unintended pregnancies and should continue to be promoted among active component service women.

More than 230,000 women serve in the active component of the U.S. military, comprising more than 17% of the active component force.1 Contraceptive health care is an increasingly important military public health issue as women’s military career opportunities have expanded into combat roles, and because the majority of women serving in the Armed Forces are of childbearing age.

All U.S. service women have access to universal, no-cost health care including contraceptive coverage. All prescription contraceptive methods, including long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs), are available at no cost in military treatment facilities. Despite this fact, rates of unintended pregnancy among service women have been estimated to be 50% higher than age-adjusted estimates in the U.S. general population.2,3 Unintended pregnancy can have a significant detrimental effect on military unit operations and readiness, especially in the deployed setting. For example, a pregnant service woman is ineligible to deploy and must be evacuated from the theater of operations if she becomes pregnant during deployment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) provides population-level estimates of contraceptive use among U.S. women. Using data collected between 2017 and 2019, the NCHS estimated that 65% of women of childbearing age used contraceptives. The most common methods used were sterilization (18%), oral contraceptives (i.e., the pill), and LARCs, used by 14% and 10% of women, respectively.4 Until 2017, similar population-based estimates of contraceptive use were unavailable for women in the U.S. military. Witkop et al. initially published findings from a comprehensive analysis of contraceptive use among women of childbearing potential in the U.S. military in 2017, which was shortly followed by a MSMR report on women’s health and contraceptive use.5,6

The objective of this report was to update prior estimates of service women who were prescribed contraceptives. Data pertaining to contraceptive use were stratified by demographic and military characteristics, as well as by contraceptive method (e.g., permanent, long-acting, short-acting). Data were also stratified by year to assess temporal trends.

Methods

The surveillance period was 1 January 2017 through 31 December 2021. The study population consisted of all active component service women aged 17–49 years who served in the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps at least 1 day during the surveillance period. Women with a history of Click to closehysterectomyA partial or total surgical removal of the Click to closeuterusAlso known as the womb, the uterus is the female reproductive organ where a baby grows. uterus. It may also involve removal of the cervix, ovaries, Fallopian tubes, and other surrounding structures. hysterectomy prior to the start of the surveillance period were excluded. Women who underwent a hysterectomy during the surveillance period were excluded from subsequent annual contraceptive use prevalence calculations. For example, a woman who underwent a hysterectomy in 2018 was not eligible to be counted for contraceptive use in 2019 or thereafter.

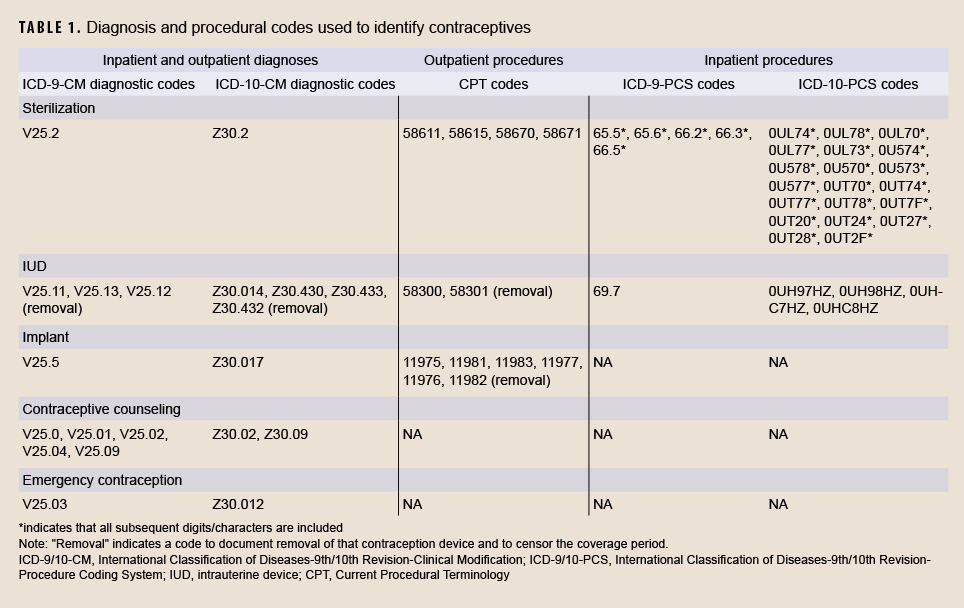

The types of contraception included in the analysis were permanent sterilization; long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), which include intrauterine devices (IUDs) and implants; short-acting reversible contraception (SARC), which include oral contraceptives, patches, vaginal rings, and injectables; contraceptive counseling; and emergency contraception. Service members were identified as using contraception on the basis of database documentation of one or more of the following: a prescription for contraception or progestins (per American Hospital Formulary Service Pharmacologic-Therapeutic Class: 681200 or 683200);7 or a procedural or diagnostic code for sterilization, contraception, or contraceptive counseling (Table 1).

Prescriptions were identified using data in the Pharmacy Data Transaction Service (PDTS) maintained in the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS). Ninth and tenth revisions of the International Classification of Diseases Clinical Modification diagnostic codes (ICD-9/10-CM), inpatient procedure codes (ICD-9/10-PCS) and current procedural terminology (CPT) codes were also identified in medical encounter records of the DMSS, which collectively contain data on hospitalizations and ambulatory visits by actively serving members in U.S. military and civilian (i.e., contracted or Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care through the Military Health System [MHS]) medical facilities worldwide. To account for contraception services received in combat theaters of operation, diagnostic codes, procedure codes, and prescriptions contained in the Theater Medical Data Store (TMDS) were also included.

Women who used multiple types of contraceptives during a given calendar year were assigned to one of four mutually exclusive groups, with group assignment as follows (in decreasing order of priority): permanent sterilization, LARCs, SARCs, and contraceptive counseling. Emergency contraception use was measured independently from the other categories of contraceptives. Time-dependent variables, such as age and military rank, were determined at the end of each calendar year for the annual calculations of prevalence percentages.

An individual was considered to be permanently sterilized from the first day of the medical encounter for permanent sterilization (via bilateral tubal ligation, oophorectomy, or salpingectomy) until the end of military service or the end of the surveillance period, whichever came first. For LARCs and SARCs, periods of contraceptive coverage were created based on the “days’ supply” for a given contraceptive type. Intrauterine devices were assigned a default 5-year days’ supply; however, Skyla® brand was assigned a 3-year days' supply and ParaGard® brand was assigned a 10-year days’ supply. Implants were assigned a default 3-year days’ supply except for both Norplant® and Jadelle® implants, which were assigned a 5-year days’ supply. The coverage period was censored on the date that the implant or IUD was removed, if there was any documentation of a removal via diagnostic or procedural codes. For SARCs, if the days’ supply information was missing from the record, then a default days’ supply of 30 days was assigned for oral contraceptives, patches, and vaginal rings, and a default 90 days’ supply was assigned for injectables. An individual was considered to have received contraceptive counseling if it was documented in the individual’s health records for the given calendar year and only if there were no other contraceptive types in use during that year. Finally, a woman was considered to have used emergency contraception for a given year if she had a medical encounter or dispensed prescription for emergency contraception at any time during that year.

Results

The number of service women of childbearing potential in active component military service during each year of the surveillance period increased from 231,433 in 2017 to 252,306 in 2021 (data not shown). However, there was an overall decline in use of any contraceptive method (sterilization, LARC, SARC, or counseling), from 58.8% in 2017 to 50.9% in 2021 (Figure 1). In 2021, the vast majority of women using any contraceptive method used either LARCs or SARCs (n=115,671).

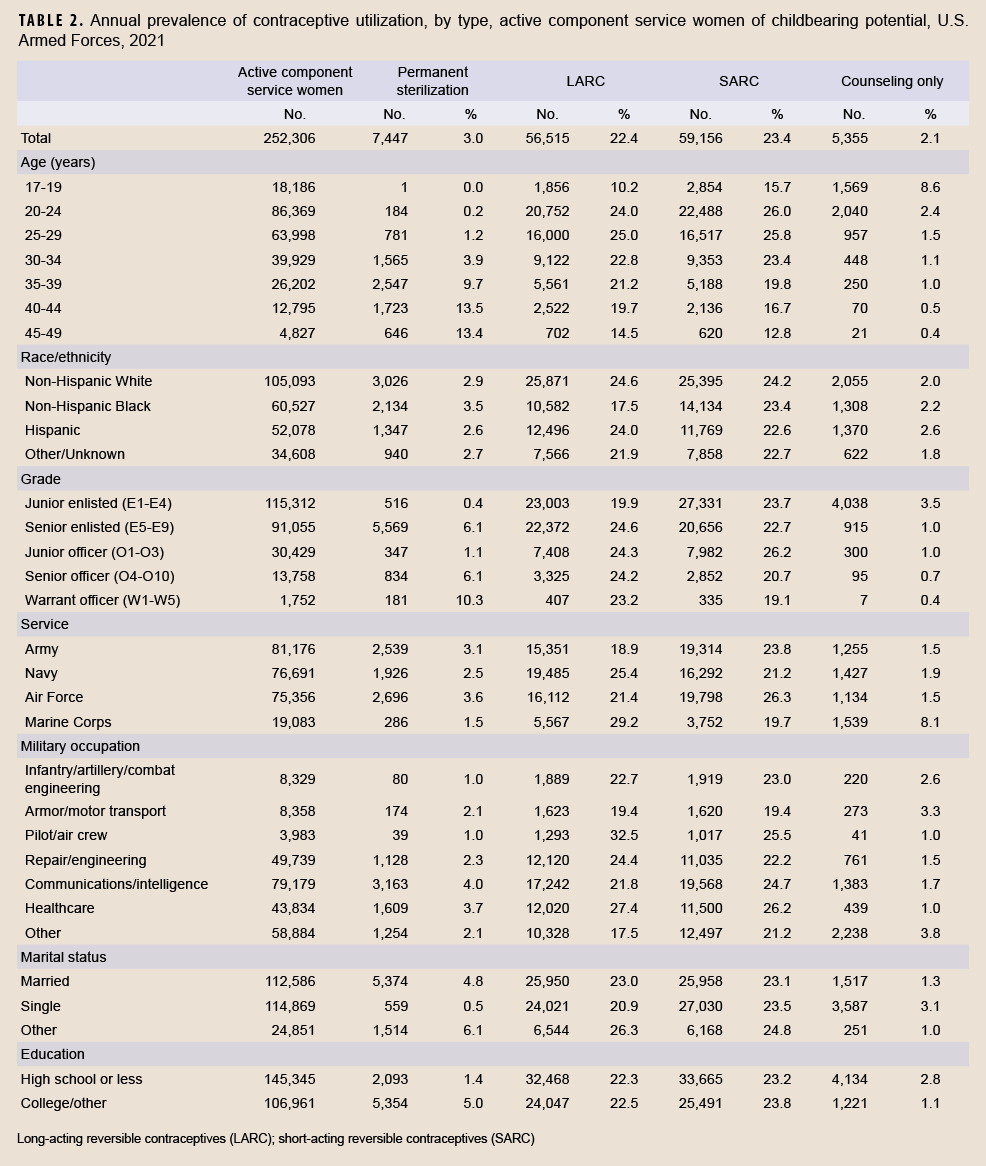

During any given year of the surveillance period, an average of 3.1% of women in service had been permanently sterilized; this prevalence decreased slightly throughout the 5-year surveillance period from 3.5% in 2017 to 3.0% in 2021 (Figure 1). In 2021, permanent sterilization was most prevalent among women aged 40–49 years at 13.4% (Table 2). The proportions of permanent sterilization prevalence were highest among non-Hispanic Black women (3.5%), those in the Air Force (3.6%), warrant officers (10.3%), those in communications/intelligence (4.0%) or healthcare (3.7%) occupations, those who completed some college or more (5.0%), and those with “other” marital status (6.1%), which would include widowed or divorced service members (Table 2).

The percentage of women who used either IUDs or implants increased to 23.8% in 2019 and then decreased to 22.4% in 2021, with an average annual prevalence of 23.0% during the surveillance period (Figure 1). In 2021, LARC use was most common among women aged 25–29 years (25.0%). LARC use was most common among Non-Hispanic Whites (24.6%) and Hispanics (24.0%), senior enlisted personnel (24.6%), pilots/aircrew (32.5%), women in the Marine Corps (29.2%), and those with “other” marital status (26.3%) (Table 2).

The annual prevalence of SARC use among service women decreased from 28.1% in 2017 to 23.4% in 2021 (Figure 1). In 2021, SARC use was most common among women aged 20–24 years (26.0%), Non-Hispanic Whites (24.2%), junior officers (26.2%), women in the Air Force (26.3%), those in healthcare occupations (26.2%), and those with “other” marital status (24.8%) (Table 2).

During any given year of the surveillance period, an average of 3.8% of active component service women used only contraceptive counseling services as a contraceptive method (Figure 1). In 2021, the average annual prevalence of the use of contraceptive counseling services only was highest among women in the youngest age group of 17–19 years (8.6%), Hispanics (2.6%), junior enlisted women (3.5%), Marine Corps personnel (8.1%), those in armor/motor transport (3.3%) or “other” (3.8%) occupations, single women (3.1%), and those with a high school education or less (2.8%) (Table 2).

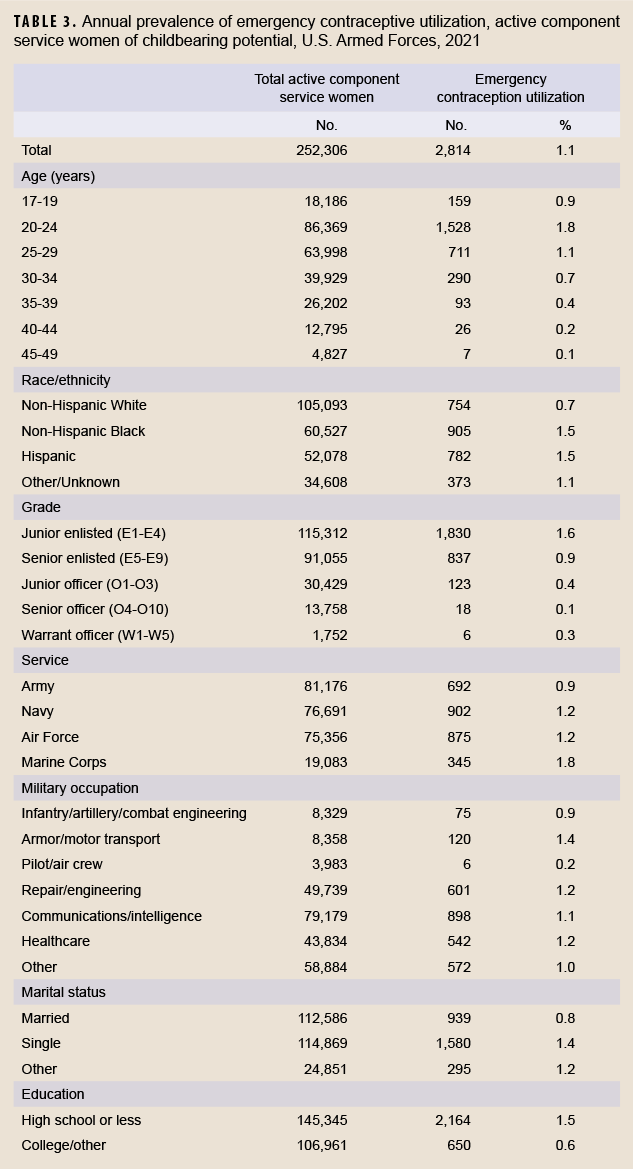

An average prevalence of 1.7% service women had prescriptions or medical encounters for emergency contraception during each year of the surveillance period (Figure 1). In 2021, emergency contraception utilization was highest among women aged 20–24 years (1.8%), Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics (1.5%), junior enlisted personnel (1.6%), women in the Marine Corps (1.8%), women in armor/motor transport occupations (1.4%), single women (1.4%), and those with a high school education or less (1.5%) (Table 3).

Editorial Comment

The current study provides population-based descriptive information on contraceptive use among U.S. service women during 2017–2021, which is needed to address questions about ready access to contraceptive care. These data demonstrate that about half of service women of childbearing potential used at least one form of contraception in 2021, and that LARCs and SARCs were the most popular types.

Between 2012 and 2016, LARC use increased in both military and civilian populations.6 This increase may have been the result of increased education programs about contraceptive and non-contraceptive benefits of LARCs as well as other programs such as walk-in contraceptive clinics. However, the current study shows that this increasing trend leveled off, with the percentage of women using LARCs decreasing from 23.8% in 2019 to 22.4% in 2021. SARC use declined slightly during the period, from 28.1% to 23.4%. In addition, there was an overall decline in use of any contraceptive method (sterilization, LARC, SARC, or counseling), from 58.8% in 2017 to 50.9% in 2021. At least part of this decreasing trend during 2020 and 2021 may have been impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic, as there were limitations on appointments and types of procedures being performed and women may have avoided contraceptive appointments during this time. This finding is concerning as LARCs are among the most effective methods for preventing unintended pregnancies and the Defense Health Board released a report in November 2020 recommending improved contraceptive education and services, particularly access to LARCs.8

Use of emergency contraception also decreased during the surveillance period. This could be interpreted as a positive finding in that it may indicate that increasing numbers of women had better access to other forms of contraception; therefore, fewer women required emergency contraception as an alternate method. However, it could also be interpreted as a negative finding if fewer women who wanted emergency contraceptives had awareness about it or access to it. Additional information about reasons for receiving or not receiving emergency contraceptives would be needed to provide a clearer interpretation of this trend.

This study shows that there are some differences in the types of contraceptives used among women in active component military service compared to women in the general U.S. population. In 2021, female service members were most likely to use SARCs (23.4%), followed by LARCs (22.4%), and permanent sterilization (3.0%). In contrast, between 2017 and 2019, women aged 15–49 years in the United States were most likely to use female sterilization as a contraceptive method (18.1%), followed by oral contraceptive pills (14.0%), LARCs (10.4%), and male condoms (8.4%).4

Some methodological limitations should be considered in interpreting the results of this study. First, estimated rates reported in this analysis may underestimate contraceptive utilization because they include only contraceptive methods purchased by the MHS or coded in the military’s electronic health records. Not captured in this analysis are contraceptives obtained elsewhere (e.g., purchased over the counter or out of pocket by the service member, provided free of charge at health fairs or in other venues, or prescribed by civilian medical providers who are not reimbursed by the MHS). Second, incorrect or nonspecific days’ supply information may have led to inaccurate estimates of the coverage periods for contraceptives. In addition, prescription data may overestimate actual utilization of SARCs if women fail to initiate or maintain use. Barrier methods such as condom use are not included in this report because these data were not available.

The analyses presented here provide insight into the evolving trends in contraceptive use among U.S. service women within the MHS. Future analyses hold the promise of providing additional information about potential impediments, facilitators, and health outcomes associated with specific contraceptive methods to enhance service women’s readiness and ability to complete their missions.

References

- Defense Manpower Data Center. Table of Active-Duty Females by Rank/Grade and Service, December 2021 (Women Only). https://dwp.dmdc.osd.mil/dwp/app/dod-data-reports/workforce-re

ports. Accessed on 12 September 2022.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Unintended pregnancy among active-duty women in the United States military, 2011. Contraception. 2015;92(6): 589–595.

- Grindlay K, Grossman D. Unintended pregnancy among active-duty women in the United States military, 2008. Obstet Gynecol 2013;21:241–246.

- Daniels K, Abma JC. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15–49: United States, 2017–2019. NCHS Data Brief, no 388. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics. 2020.

- Witkop CT, Webber BJ, Chu KM, Clark LL. Contraception use among U.S. servicewomen: 2008–2013. Contraception. 2017;96(1):47–53.

- Stahlman S, Witkop CT, Clark LL, Taubman SB. Contraception among active component service women, U.S. Armed Forces, 2012–2016. MSMR. 2017;24(11):10–21.

- American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. AHFS Therapeutic Classification. https://www.ashp.org/products-and-services/database-licensing-and-integration/ahfs-therapeutic-classification?loginreturnUrl=SSOCheckOnly. Accessed 30 September 2022.

- Defense Health Board. Active-Duty Women’s Health Care Services. https://www.health.mil/Reference-Center/Reports/2020/11/05/Active-Duty-Womens-Health-Care-Services. Accessed 17 September 2022.