What are the new findings?

Non-Hispanic Blacks, as well as those who were female, younger, of lower rank, with lower education levels, and those serving in the Army were less likely to initiate COVID-19 vaccination after adjusting for other factors. Once initiated, completion of the vaccine series was similar across demographic groups. WHAT IS THE IMPACT ON READINESS AND FORCE HEALTH PROTECTION? Vaccination is an important intervention to mitigate the threat of COVID-19 to the U.S. military. Significant disparities in vaccination by race, sex, and other factors exist in military populations. The U.S. military must continue to assess and address factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, including disparities, to ensure maximum force health protection against the virus.

Abstract

The objective of this study was to assess overall vaccine initiation and completion in the active component U.S. military, with a focus on racial/ethnic disparities. From 11 Dec. 2020 through 12 March 2021, a total of 361,538 service members (27.2%) initiated a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine. Non-Hispanic Blacks were 28% less likely to initiate vaccination (95% confidence interval: 25%–29%) in comparison to non-Hispanic Whites, after adjusting for potential confounders. Increasing age, higher education levels, higher rank, and Asian/Pacific Islander race/ethnicity were also associated with increasing incidence of initiation after adjustment. When the analysis was restricted to active component health care personnel, similar patterns were seen. Overall, 93.8% of those who initiated the vaccine series completed it during the study period, and only minor differences in completion rates were noted among the demographic subgroups. This study suggests additional factors, such as vaccine hesitancy, influence COVID-19 vaccination choices in the U.S. military. Military leadership and vaccine planners should be knowledgeable about and aware of the disparities in vaccine series initiation.

Background

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the virus responsible for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has dramatically affected the global population. Its impact on the health and readiness of the U.S. military has been demonstrated in several important populations such as shipboard sailors and trainees.1-3 The virus has affected the full range of military operations through restrictions of movement, workspace capacity limits, and testing protocols imposed upon service members.4-8 Incidence of COVID-19 has been shown to be higher in non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics in the U.S., and it has also been shown that non-Hispanic Blacks have a higher risk of COVID-19 related hospitalization.9 In the U.S. military, unpublished analyses have indicated higher rates of infection and hospitalization among non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic U.S. service members (John Young, DProf, EML, email communication, March 2021).

Three vaccines are currently available for COVID-19, authorized under emergency use. Two mRNA vaccines were approved in December 2020, and an adenovirus- vectored vaccine was approved in late February 2021. The mRNA vaccines from Pfizer and Moderna are over 90% effective and are recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to prevent symptomatic COVID-19.10-12 They were immediately made available for health care personnel (HCP) within the active component U.S. military, and have subsequently been allocated according to occupational risk during initial phases as defined in the Department of Defense (DOD) COVID-19 Vaccination Population Schema which is consistent with the prioritization recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).13,14

Prior to vaccine availability, a number of surveys in the general U.S. population suggested that racial and ethnic minorities were less willing to accept the COVID-19 vaccine.15, 16 Although recent evidence suggests that vaccine hesitancy, characterized by vaccine delay or vaccine refusal,17 may be decreasing in all groups, non-Hispanic Blacks continue to report higher levels of vaccine hesitancy. The CDC has reported that among HCP and long-term care facility residents whose race/ethnicity was known, only 5.4% of vaccine recipients were non-Hispanic Black even though 16% of the health care workforce and 14% of residents of long-term care facilities were non-Hispanic Blacks.18 Other preliminary data have suggested that non- Hispanic Blacks had a 29% lower odds of vaccination.19 However, the CDC has also reported that 88% of those who received a first dose of COVID-19 vaccination completed the series, with only small differences by race, age, and sex.20

Many media reports stated that 33% or more of military service members are refusing the vaccine, but these reports have focused on anecdotes and preliminary data coming out of Fort Bragg or other specific locations.21 Currently, no data on DOD-wide COVID-19 vaccine initiation or completion in military populations are publicly available. The objective of this study was not only to understand overall COVID-19 vaccine initiation and completion in the active component U.S. military, but also to investigate factors associated with vaccine initiation and completion, with special attention to assessing racial and ethnic disparities. As HCP were the focus of the first phase of vaccinations, this study also was intended to specifically assess vaccination initiation and completion among active component HCP.

Methods

Data for this study were obtained from the Defense Medical Surveillance System (DMSS), which relates demographic information to health care encounters involving active component service members (ACSMs) of the U.S. Armed Forces in direct and Click to closePurchased CareThe TRICARE Health Program is often referred to as purchased care. It is the services we “purchase” through the managed care support contracts.purchased care. The DMSS also contains administrative records for vaccinations received from the immunization database of the Defense Enrollment Eligibility Reporting System (DEERS).

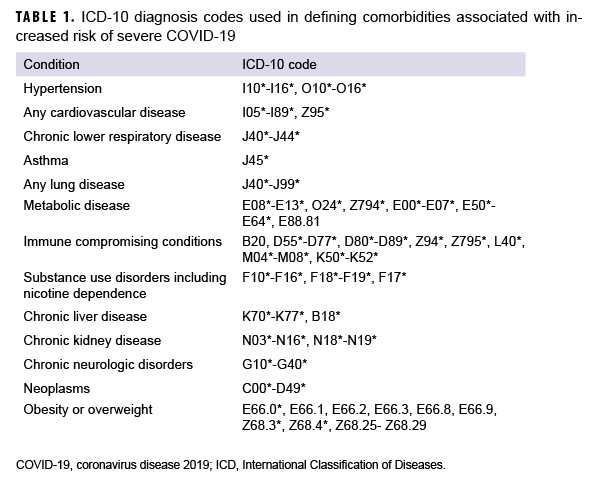

For the primary analysis, all ACSMs serving in the Army, Navy, Air Force, or Marine Corps in Dec. 2020 were followed through March 12, 2021 for initiation and completion of the Moderna (CVX code=207) or Pfizer (CVX code=208) COVID-19 mRNA vaccine series. Only small quantities of the Johnson & Johnson vaccine had been used in the U.S. military prior to the end of the study period, so its use was excluded from this analysis. Initiation was defined as having received at least one dose by 12 March 2021. Among those who initiated, completion was measured by identifying those who completed a second dose at least 17 days after the first dose of the Pfizer vaccine or 24 days for the Moderna vaccine.14 Completion was assessed only among the population of ACSMs who initiated prior to January 29, 2021 in order to allow 6 weeks to assess completion only among those who would have been eligible to complete the dose series by 12 March 2021, which was the end of the study surveillance period. Using these criteria, the proportion of service members who initiated or completed the dose series was described. The following racial and ethnic groups were used for categorization: Non- Hispanic Whites, non-Hispanic Blacks, Hispanics, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and Other (Other race/ethnicity includes those with an unknown race/ethnicity). Covariates included sex, service, age, military rank, military occupation, marital status, education level, geographic region of assignment, prior history of positive COVID-19 test, and comorbidities. Individuals were considered to have a comorbidity if they had an inpatient or outpatient medical encounter with an eligible International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-10-CM) diagnosis code recorded in any diagnostic position. The list of ICD-10 codes for each comorbidity is presented in Table 1. Adjusted risk ratio (ARR) estimates were calculated using Poisson regression with robust error variance, and the adjusted models controlled for all the covariates previously described. All analyses were performed using SAS/ STAT software, version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

A secondary analysis was accomplished by replicating the primary analysis in the HCP subgroup within the ACSM population. HCP were categorized according to their primary DOD occupation codes. These occupation codes were grouped into subcategories that included: Physicians and Physician Assistants, Dentists, Nurses, Biomedical Sciences and Allied Health Personnel (includes technicians ranging from clinical technicians to laboratory and materiel support), Healthcare Administration, and Preventive Medicine elements. Preventive Medicine elements included: Undersea/ Aviation Medicine, Aviation/Aerospace Medicine, Undersea Medicine, Occupational Medicine, and Preventive Medicine. Although veterinarians are coded as health care personnel, they were excluded from this portion of the analysis. ARR estimates were calculated adjusting for the same covariates as in the primary analysis.

Results

Active component service members

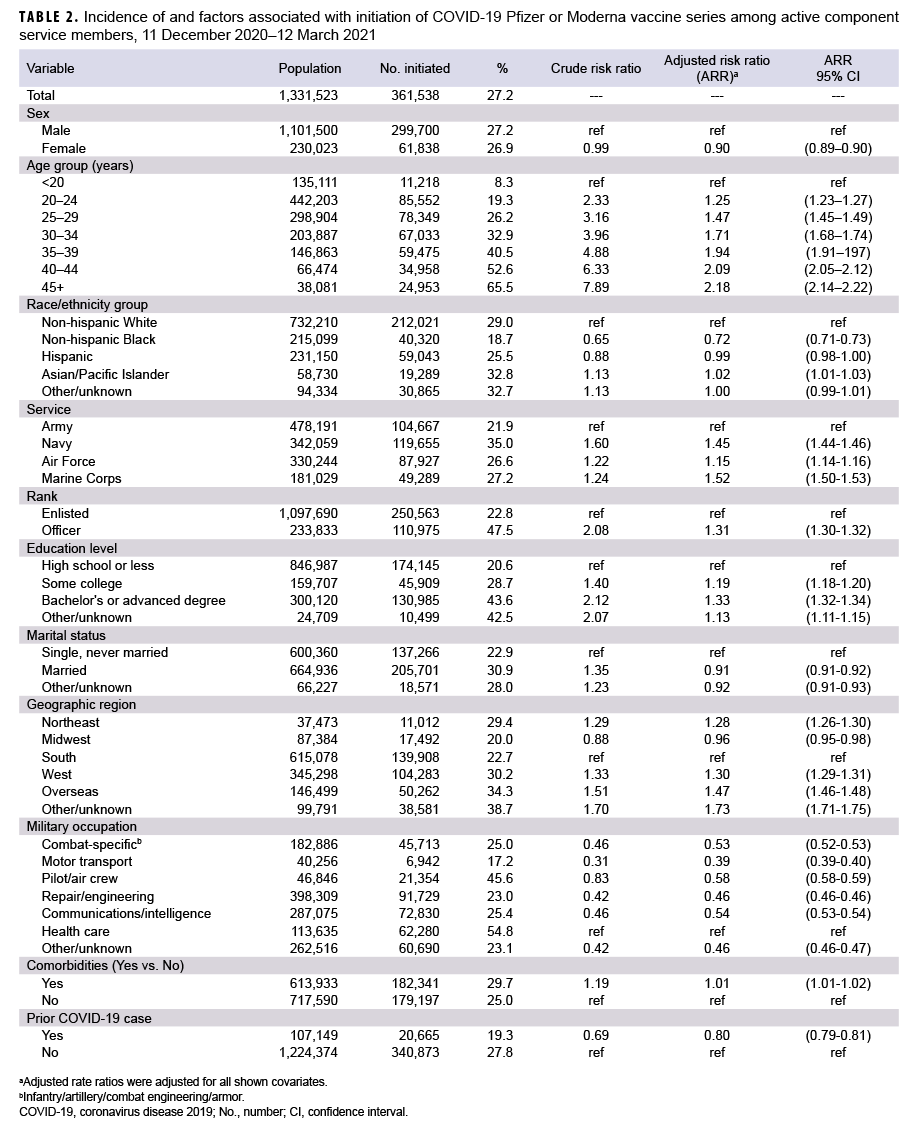

Among 1,331,523 ACSMs in service during Dec. 2020, 361,538 (27.2%) initiated COVID-19 vaccination by 12 March 2021 (Table 2). Of the non-Hispanic Whites, 29% initiated, compared to 18.7% of non-Hispanic Blacks and 25.5% of Hispanics. The reduction in COVID-19 vaccine initiation seen among non-Hispanic Blacks persisted in the adjusted analysis, with non-Hispanic Blacks being 28% less likely to initiate compared to non-Hispanic Whites (95% confidence interval [CI]: 27%–29%). However, Hispanics had a similar rate of initiation compared to non-Hispanic Whites (ARR=0.99; 95% CI: 0.98–1.00). It is notable that Asian/Pacific Islanders were the only race/ethnicity group to have had a higher rate of initiation (ARR=1.02; 95% CI: 1.01–1.03) compared to non-Hispanic Whites. After adjusting for other factors, females were 10% less likely to initiate than males (95% CI: 9%–10%), and service members who had a history of COVID- 19 infection were 20% less likely to initiate compared to those without prior COVID- 19 infection (95% CI: 19%–21%). Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps members were 45%, 15% and 52% more likely, respectively, to initiate compared to Army members in the adjusted model. Increasing age, greater education levels, and higher rank were also associated with increasing proportions of initiation after adjustment. Service members assigned to southern and midwestern regions had the lowest incidence of initiation. Among all DOD occupation categories, HCP and pilots had the highest incidence of initiation. In general, service members with comorbidities initiated at a slightly higher proportion compared to those who did not have a comorbidity.

However, those with a diagnosed substance use disorder (including nicotine dependence), had lower initiation rates compared to those without this diagnosis (24.7% vs. 27.5%, respectively).

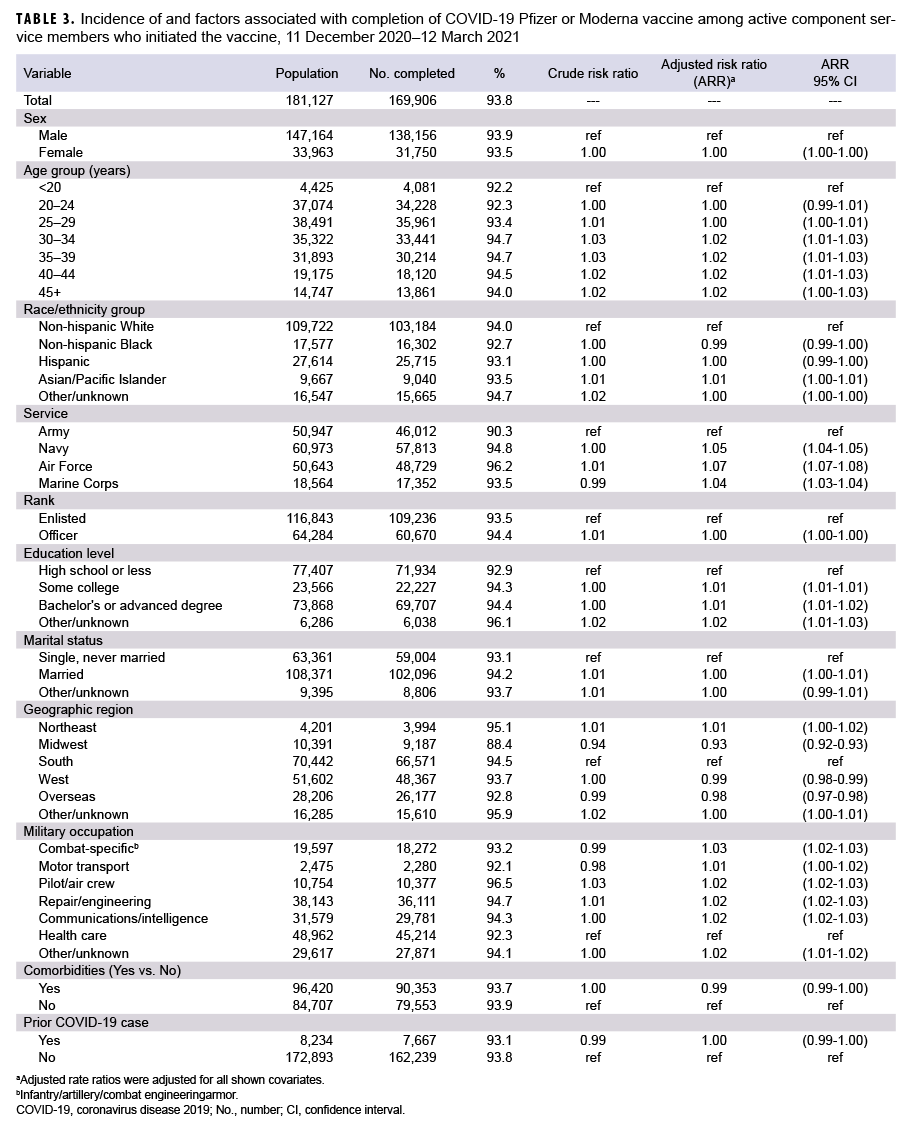

Among 181,127 ACSMs who initiated COVID-19 vaccination by 29 Jan. 2021, 169,906 (93.8%) completed the COVID- 19 vaccine series by 12 March 2021 (Table 3). Crude differences in vaccine completion were small, and no significant associations with race/ethnicity group or sex were seen in the adjusted model. Following adjustment, individuals in the Army were slightly less likely to complete the series, as were individuals vaccinated at midwestern locations (and to a lesser extent, locations in the west and overseas).

Active component health care personnel

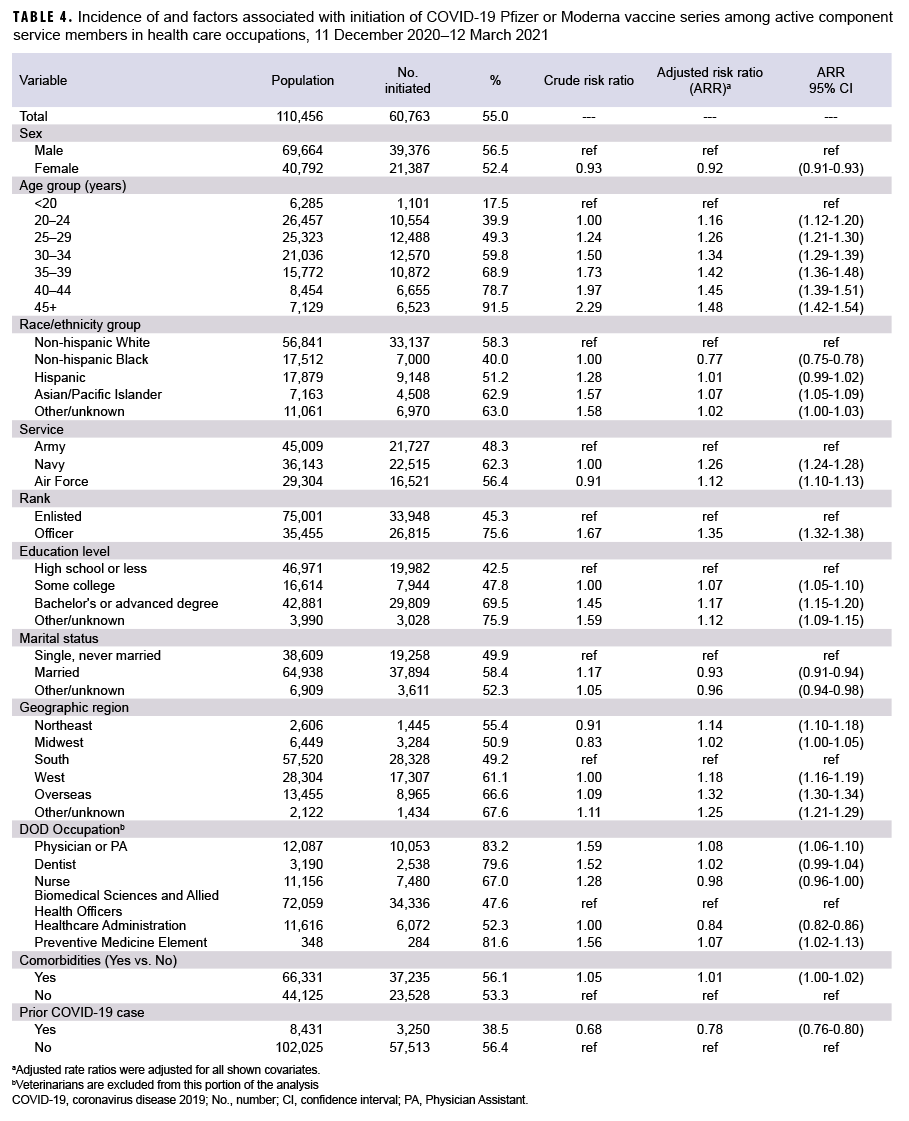

Among the 110,456 active component HCP, 60,763 (55.0%) initiated a COVID-19 vaccine series (Table 4). As previously noted, this population excludes veterinarians. The associations seen between initiation and demographic and clinical factors in the HCP population were similar to those seen in the broader ACSM population (Table 4). Of note, non-Hispanic Black HCP were 23% (95% CI: 22%–25%) less likely to initiate vaccination compared to non-Hispanic White HCP in adjusted analysis, but Asian/Pacific Islanders again were 7% more likely. Female HCP were 8% (95% CI: 7%–9%) less likely to initiate than male HCP. Within the HCP subgroup, physicians and Preventive Medicine elements had the highest incidence of vaccination (83.2% and 81.6%, respectively), followed by dentists, nurses, health care administrators, and allied biomedical sciences personnel. Of note, those who had a history of COVID-19 infection were 22% (95% CI: 20%–24%) less likely to initiate compared to those who were not. Among HCP who initiated COVID-19 vaccination by 29 January 2021, 92% completed the COVID-19 vaccine series by 12 March 2021 (data not shown). The demographic differences were similar to those seen in the broader ACSM population.

Editorial Comment

This interim report describes COVID- 19 vaccine uptake within the first 3 months of vaccine availability. Findings from this study indicate that from 11 Dec. 2020 through 12 March 2021, a total of 361,538 (27.2%) ACSMs initiated a COVID-19 mRNA vaccine series, including 60,763 (54.8%) HCP. Non-Hispanic Black service members were 28% less likely to initiate compared to non-Hispanic White service members, and non-Hispanic Black HCP were 23% less likely than non-Hispanic White HCP, after adjusting for potential confounders. In addition, females were 10% less likely to initiate than males, and service members who had a history of COVID-19 infection were 20% less likely to initiate. Navy, Air Force, and Marine Corps members were 45%, 15% and 52% more likely, respectively, to initiate compared to soldiers. Increasing age, greater education levels, higher rank, and Asian/Pacific Islander race/ethnicity were also associated with increasing incidence of COVID-19 vaccine initiation after adjustment. In the analysis restricted to ACSM health care personnel, the first occupational group to be offered the vaccine, similar associations were demonstrated as were seen in the broader active component population. Overall, 93.8% of those who initiated a COVID-19 vaccine series completed it, and only minor differences between demographic groups were found in vaccine completion.

Little published literature exists on current COVID-19 vaccination initiation or completion with which to compare this study. In a recent Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, non-Hispanic Blacks were found to constitute a lower proportion of vaccines (5.4%) than would have been expected on the basis of the proportions of non-Hispanic Blacks among populations of health care workers (16%) and nursing home residents (14%).18 In that same study, females were found to constitute a lower proportion of vaccines (63%) despite constituting nearly 75% of both populations. Additionally, recent preliminary data obtained from survey responses to a smartphone application suggest a 29% lower odds of having received the vaccination among non-Hispanic Black U.S. participants in comparison to non-Hispanic Whites, which was similar between the general community and among health care workers.19 Despite the differences in methodology and study population sizes, the findings from this study were very similar to the smartphone study, which did not report differences in vaccination by sex. Finally, the CDC report of 88% completion of vaccine series was similar to but slightly lower than that found in this study.20 This small difference may be due to the different lengths of the follow-up periods or the different demographic and behavioral characteristics between the populations. Both the CDC report and this study found only minor differences in groups with respect to vaccine series completion.

A key strength of this study is its large, enumerated study population. This is the first study to investigate determinants of vaccine receipt for a vaccine authorized under emergency use and intended for all ACSMs. U.S. military ACSMs are provided universal eligibility for health care, reducing potential sources of systemic differences in health care access related to transportation, insurance, availability, or age which may be seen in civilian populations, and which may lead to health care disparities. Compared to other studies with higher rates of unknown race approximating 50% in some cases,18 only 2% of ACSMs have unknown race/ ethnicity in the demographic records contained in DMSS. Finally, vaccine initiation and completion outcome data are based on observation rather than self-report.

This study is not without limitations. First, as these vaccines were approved under Emergency Use Authorization, by military regulation they were offered on a voluntary basis only. In addition, ACSMs in certain populations and roles were not eligible for vaccination during the surveillance period.22 Because data were not available on specifically who was offered vaccination, this could not be adjusted for and to some extent this may confound the association between race/ethnicity and vaccine initiation. This voluntary immunization program is distinct from immunization programs governing vaccines for other respiratory pathogens in the DOD which are considered mandatory, such as vaccines for influenza and measles, mumps, and rubella.23

There are many complex individual, interpersonal, military, and societal factors influencing access to and willingness to receive this voluntary vaccination which were not measured here. Second, there is potential for misclassification of vaccination status if significant errors or delays in documentation existed. Covariates such as geographic region, marital status, occupation, etc., may have changed between Dec. 2020 and the time of vaccine receipt; however, these differences are expected to be small due to the short surveillance period. In addition, race is self-reported, in contrast to other objective covariates such as age and rank. Importantly, the results presented here may change after more time has passed and more vaccines become available or accessible. The findings from recent surveys of waning vaccine hesitancy over time suggest that the associations from this study could be further attenuated as behaviors change over time.19 Finally, vaccine declination was not assessed in this study because these data were not available.

Vaccination is an important intervention to mitigate the threat of COVID-19 to the U.S. military. Despite universal eligibility for health care in the U.S. military, disparities in COVID-19 vaccine initiation exist by race, as well as by sex, rank, and education. Among both the entire ACSM population and its HCP subgroup, vaccine hesitancy among racial and ethnic groups mirror that which has been observed within the U.S. population. This suggests that forces external to the U.S. military, such as interpersonal and societal factors, also contribute towards vaccine hesitancy among military service members, as has been suggested for other disease processes.24 Military leadership and vaccine planners should be knowledgeable about and aware of the disparities in vaccine initiation. Messaging and other outreach efforts should aim to reduce or eliminate vaccine hesitancy in general, with attention focused on reducing vaccine disparities.

Vaccine declinations should be addressed, with further description of reasoning for declinations, as this would serve to better understand the most common behaviors and beliefs of key demographic groups. Surveys and mixed-methods participatory research are potential avenues to identify factors which mitigate vaccine hesitancy. The U.S. military must continue to assess and address factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy, including disparities, to ensure maximum force health protection against the virus.

Author affiliations: Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Drs. Mancuso and Lang); Armed Forces Health Surveillance Division, Silver Spring, MD (Drs. Stahlman, Wells, Chauhan, Patel, and Ms. Fedgo)

Acknowledgements: The authors thank Amy Costello, MD, MPH (Col, USAF) and Margaret Ryan, MD, MPH (CAPT USN [ret], DHA/IHD) for substantial contributions including proofreading and providing critical details related to the study background and design. They also thank John Young, DProf, EML (USUHS) for critical details related to the background of this study.

Disclaimer: The opinions and assertions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the U.S. Government.

References

- Kasper MR, Geibe JR, Sears CL, et al. An Outbreak of Covid-19 on an Aircraft Carrier. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2417–2426.

- Letizia AG, Ge Y, Goforth CW, et al. SARSCoV-2 Seropositivity among US Marine Recruits Attending Basic Training, United States, Spring–Fall 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2021;27(4):1188–1192.

- Letizia AG, Ramos I, Obla A, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Transmission among Marine Recruits during Quarantine. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(25):2407–2416.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness. Force Health Protection Guidance (Supplement 11) – Department of Defense Guidance for Coronavirus Disease 2019 Surveillance and Screening with Testing. 12 June 2020.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness. Force Health Protection Guidance (Supplement 14) – Department of Defense Guidance for Personnel Traveling During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. 29 December 2020.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness. Force Health Protection Guidance (Supplement 16) – Department of Defense Guidance for Deployment and Redeployment of Individuals and Units During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. 16 March 2021.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness. Force Health Protection Guidance (Supplement 17) – Department of Defense Guidance for the Use of Masks, Personal Protective Equipment, and Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. 17 March 2021.

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness. Force Health Protection Guidance (Supplement 18) – Department of Defense Guidance for Protecting All Personnel in Department of Defense Workplaces During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 Pandemic. 17 March 2021.

- Price-Haywood EG, Burton J, Fort D, Seoane L. Hospitalization and Mortality among Black Patients and White Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(26):2534–2543.

- Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Use of Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(50):1922–1924.

- Oliver SE, Gargano JW, Marin M, et al. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices' Interim Recommendation for Use of Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine - United States, December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;69(5152):1653–1656.

- Jones NK, Rivett L, Seaman S, et al. Single-dose BNT162b2 vaccine protects against asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection. Elife. 2021;10:e68808.

- Defense Health Agency-Interim Procedures Memorandum 20-004: Department of Defense (DOD) Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Vaccination Program Implementation. 2021.

- Interim Clinical Considerations for Use of mRNA COVID-19 Vaccines Currently Authorized in the United States. Accessed 25 March 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/covid-19/info-byproduct/clinical-considerations.html

- Daly M, Robinson E. Willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 in the US: Longitudinal evidence from April–October 2020. Am J Prev Med. 2021; S0749-3797(21)00088-X.

- Nguyen KH, Srivastav A, Razzaghi H, et al. COVID-19 Vaccination Intent, Perceptions, and Reasons for Not Vaccinating Among Groups Prioritized for Early Vaccination - United States, September and December 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(6):217–222.

- Dube E, Laberge C, Guay M, Bramadat P, Roy R, Bettinger J. Vaccine hesitancy: an overview. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013;9(8):1763–1773.

- Painter EM, Ussery EN, Patel A, et al. Demographic Characteristics of Persons Vaccinated During the First Month of the COVID-19 Vaccination Program - United States, Dec. 14, 2020–January 14, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(5):174–177.

- Nguyen LH, Joshi AD, Drew DA, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy and uptake. medRxiv. 2021.02.25.21252402.

- Kriss JL, Reynolds LE, Wang A, et al. COVID- 19 Vaccine Second-Dose Completion and Interval Between First and Second Doses Among Vaccinated Persons - United States, December 14, 2020–February 14, 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(11):389–395.

- Myers M. About a third of troops have turned down the COVID-19 vaccine. Military Times. 17 February 2021. Accessed 24 March 2021. https://www.militarytimes.com/news/your-military/2021/02/17/about-a-third-of-troops-haveturned-down-the-covid-19-vaccine/

- Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Personnel and Readiness. Department of Defense Instruction 6200.02. Application of Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Rules to Department of Defense Force Health Protection Programs. 27 Feb. 2008

- Headquarters, Departments of the Army, the Navy, the Air Force, and the Coast Guard. Army Regulation 40–562. Immunizations and Chemoprophylaxis for the Prevention of Infectious Diseases. 7 Oct. 2013.

- Harris GL. Reducing Healthcare Disparities in the Military Through Cultural Competence. J Health Hum Serv Adm. 2011;34(2):145–181.