Background

In this issue of the MSMR, an overview of the incidence of scarlet fever in Military Health System beneficiaries under 17 years of age is presented.1 The following provides a brief comparison of the characteristics of scarlet fever to other erythematous rashes associated with infectious diseases.

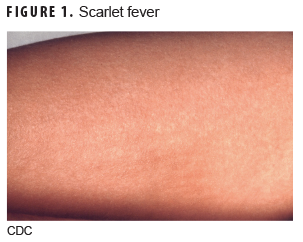

Scarlet fever

Scarlet fever (Figure 1) is caused by group A beta-hemolytic streptococcus bacteria.2 The incubation period is generally 2–5 days with prodromal symptoms of fever, sore throat, abdominal pain, and vomiting for 12–48 hours. The rash typically starts on the face or neck and rapidly spreads to the whole body, including the hands and feet, and is characterized as red, maculopapular, rough lesions commonly referred to as a sandpaper rash. Areas of skin folding—such as the groin, armpits, elbows, and knees—will typically develop a darker redness than other areas with the rash. The duration of the rash is variable from a few days to about 1 week and may be followed by desquamation or peeling of the skin for 1–3 weeks. Associated clinical findings include tonsillitis with cervical lymphadenopathy and a strawberry tongue.2,3

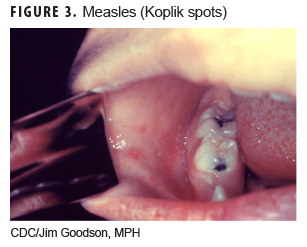

Measles

The rubeola virus is the etiologic agent for this infection (Figure 2). After an incubation period of 8–12 days, prodromal symptoms of fever, cough, coryza, and conjunctivitis begin.4 The rash appears 3–4 days after prodromal symptoms and begins around the ears and hairline on the face and spreads downward, covering the face, trunk, and arms by the second day. Initially the rash is red and maculopapular and becomes confluent by day 3. The rash typically lasts about 5 days and then fades in the same sequence as it appeared. Desquamation or peeling of the skin can follow the rash but does not occur on the palms or soles. The rash is not pruritic. Associated clinical findings include prodromal signs and Koplik spots (Figure 3) in the oral mucosa (white pinpoint-sized lesions with a reddened base).2,4,5

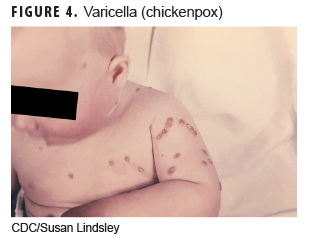

Varicella (chickenpox)

This disease (Figure 4) is caused by the initial infection with varicella-zoster virus. The incubation period is 14–16 days with a prodromal period of 0–2 days including fever, headache, malaise, abdominal pain, and decreased appetite. The rash may start on the chest, back, and face and then spreads over the whole body and is characterized by progression from vesicles in a teardrop shape that then crust and scab over. Patients typically have different stages of the rash on the body when examined. Usually within 24–48 hours, the vesicles progress to the crusting stage. All lesions progress to crusting by 5–10 days. The rash is very itchy. Associated clinical findings include high fever and lymphadenopathy.

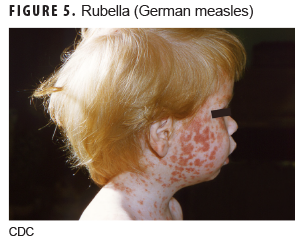

Rubella (German measles)

Rubella (Figure 5) is caused by the rubella virus and has an incubation period of 16–18 days with a prodromal period of 1–5 days before rash development, which consists of low-grade fever (less than 101°F), headache, conjunctivitis, malaise, lymphadenopathy, cough, and rhinorrhea.6 The rash typically starts on the face and spreads to the extremities over the next 48 hours and appears as small, fine, maculopapular, pink lesions that tend not to coalesce as the measles rash does. Associated clinical findings include distinctive lymphadenopathy including posterior cervical, suboccipital, and posterior auricular nodes.2,5

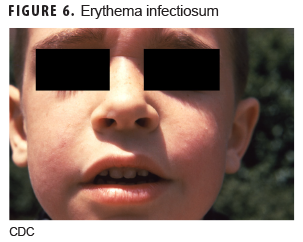

Erythema infectiosum

This illness (Figure 6) is caused by human parvovirus B19. The incubation period is 1–2 weeks, and a prodromal period lasts 2–5 days before the rash appears and consists of low-grade fever, coryza, headache, malaise, nausea, and diarrhea.7 The first stage of the rash usually begins on the cheeks as a solid bright red eruption with circumoral pallor, giving it a "slapped cheek" appearance. Over the next 1–4 days, the second stage of the rash develops, which is characterized by a maculopapular rash spreading to the trunk and extremities. If central clearing of the rash occurs, it will have a lacelike, reticular pattern. The rash is pruritic and typically fades over 1–3 weeks. Associated clinical conditions include arthropathy; transient aplastic crisis; chronic red cell aplasia; hydrops fetalis; and papular, pruritic eruptions on the hands and feet ("gloves and socks" syndrome).2,5

Roseola (exanthema subitum)

Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) is the most common cause of this illness (Figure 7), but other viral causes include HHV-7, enteroviruses, adenoviruses, and parainfluenza type 1. The incubation period is 5–15 days, and a prodromal period consists of high fevers (104–105°F) for 3–4 days.8 Febrile convulsions may occur in young children. The rash appears as the fever resolves and begins on the chest and abdomen and spreads to the face and extremities and appears as small, separate, rose-pink, blanching, macular or maculopapular lesions. The rash typically resolves after 1–2 days without desquamation. The rash is not itchy. In addition to high fever, occipital adenopathy is a clinical finding along with the rash.2,5

Author affiliations: Department of Preventive Medicine and Biostatistics, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, Bethesda, MD (Maj Sayers); Defense Health Agency, Armed Forces Health Surveillance Branch (Dr. Clark).

Disclaimer: The contents described in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect official policy or position of Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences, the Department of Defense, or Departments of the Army, Navy, or Air Force.

References

- Sayers DR, Bova ML, Clark LC. Brief report: Diagnoses of scarlet fever in Military Health System (MHS) beneficiaries under 17 years of age across the MHS and in England, 2013–2018. MSMR. 2020;27(2):26–27.

- Allmon A, Deane K, Martin KL. Common skin rashes in children. Am Fam Physician. 2015;92(3):211–216.

- Basetti S, Hodgson J, Rawson TM, Majeed A. Scarlet fever: a guide for general practitioners. London J Prim Care (Abingdon). 2017;9(5):77–79.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Measles. In: Red Book: 2018–2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:537–550.

- Garcia JJG. Differential diagnosis of viral exanthemas. Open Vaccine J. 2010;3:65–68.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Rubella. In: Red Book: 2018–2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018;869–883.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Parvovirus B19 (Erythema Infectiosum, Fifth Disease). In: Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:602–606.

- Committee on Infectious Diseases, American Academy of Pediatrics. Human herpesvirus 6 (including roseola) and 7. In: Red Book: 2018–2021 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:454–457.