Abstract

Careless responding to surveys has not been sufficiently characterized in military populations. The objective of the current study was to determine the proportion and characteristics of careless responding in a 2019 survey given to a large sample of U.S. Army soldiers at 1 installation (n = 4,892). Two bogus survey items were asked to assess careless responding. Nearly 96% of soldier respondents correctly answered both bogus items and 4.5% incorrectly answered at least 1 bogus question. In the adjusted multiple logistic regression model, race and marital status were associated with incorrect answers to bogus item questions after controlling for all other covariates. Specifically, the odds of Black respondents incorrectly answering the bogus items (adjusted odds ratio [AOR]: 2.53; 95% CI: 1.74–3.68) were more than 2.5 times those of White respondents. The recommendations that stem from the results of surveys can influence policy decisions. A large proportion of careless responses could inadvertently lead to results that are not representative of the population surveyed. Careless responding could be detected through the inclusion of bogus items in military surveys which would allow researchers to analyze how careless responses may impact outcomes of interest.

What are the new findings?

Careless responding to survey questions has not been previously studied in military populations. In a behavioral health survey with 2 bogus items used to assess careless responding, 4.5% of soldier respondents provided at least 1 incorrect answer. In an adjusted multiple logistic regression model, race (Black) and marital status (other) were associated with bogus item passage. Black respondents had odds of failing the bogus items that were more than 2.5 times those of White respondents.

What is the impact on readiness and force health protection?

Data from surveys may be used to make public health decisions at both the installation and the Department of the Army level. This study demonstrates that a vast majority of soldiers were likely sufficiently engaged and answered both bogus items correctly. Future surveys should continue to investigate careless responding to ensure data quality in military populations.

Background

Public health surveys are routinely used to determine health disparities in a given population. However, less attentive responses to survey questions (“careless responding”) could introduce bias and affect the reliability and validity of health measures.1,2,3 Thus, careless responding may change the magnitude and direction of estimates which could lead to misleading results1,2,3 and erroneous public health recommendations. Previous studies on careless responding to surveys have been primarily conducted outside of public health.4–10 These studies have focused on various methods to detect, describe, and reduce careless responding.4–10 One strategy to detect careless responses to survey questions is via bogus items. A bogus item is a survey question designed to elicit the same answer from all respondents, which is typically an obvious correct answer, such as “I was born on planet Earth.” Bogus items are inexpensive to include in a survey, require minimal computation, and minimize Type I error (i.e., falsepositives) due to the high likelihood for participants to answer correctly (e.g., affirming that the American flag is “red, white, and blue” is readily answered by people who live in the U.S.).8 However, false negatives (i.e.,answering correctly for the wrong reason) may be likely if respondents answer questions in a routine pattern that has nothing to do with the questions’ content (e.g., answering “strongly agree” to everyquestion). Furthermore, incorrect responses to bogus items may not be representative of engagement throughout the survey. Instead, there may be a lapse in a respondent’s engagement or attentiveness in different sections of the survey or accidental selection of an incorrect response.8,10 Alternatively, incorrect responses to bogus items may reflect measurement error due to the bogus items used. The modal proportion of careless respondents in a typical survey is near 10%.7,8,11

The recommendations that stem from the results of surveys can influence policy decisions. However, careless responding has not yet been studied in military populations. The prevalence of careless responding and associated factors in military surveys warrants evaluation to better understand how careless responding may affect outcomes of interest.

At the time of this analysis, no prior published studies had evaluated the frequency or predictors of careless responding in the U.S. military. The primary objective of this study was to quantify careless responding in a survey of a large U.S. Army population at a single U.S. Army installation using 2 bogus items. The secondary objective was to describe the association between demographic and military characteristics and correct responses to the bogus items.

Methods

Study population

This secondary analysis used survey data from a behavioral health epidemiological consultation (EPICON) conducted at a U.S. Army installation in 2019 by the U.S. Army Public Health Center’s Division of Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes Practice. An anonymous, online, behavioral health survey was provided to soldiers via an Operational Order (OPORD) to estimate the prevalence of adverse behavioral and social health outcomes, following a perceived increase in suicidal behavior at the installation. The OPORD was distributed from the commander of the installation to subordinate units. The survey was web-based and estimated in pilot testing to require 25 minutes to complete. Survey data were collected using Verint Systems software which allowed soldier respondents to complete the survey via any web-enabled device.12 The survey was open for 28 calendar days. Respondents could start, save, and submit the survey at any point between the opening and closing dates of the survey period. Respondents were not incentivized to complete the survey (i.e., no monetary, gift, time, or other rewards were offered). Only respondents who selected “military” as their duty status in the initial screening question were included in the final dataset. Additionally, respondents who did not answer both of the bogus items were excluded from the analysis.

Respondents’ demographic and military characteristics were collected at the beginning of the survey to reduce the likelihood of omission. Demographic characteristics included sex, age group, race (White/Caucasian, Black/African American, Asian/Pacific Islander, and other/multiracial), ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic), education level, and marital status. Race and ethnicity were assessed based on responses to the question, “What is your race/ethnicity? Select all that apply.” The response options included 1) White, 2) Black or African American, 3) Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin, and 4) other race, ethnicity, or origin. Respondents who selected “other race, ethnicity or origin” were classified as “other” and those who selected multiple racial groups were classified as “multiracial.” Due to small cell sizes, the “other” and “multiracial” categories were combined. Regarding ethnicity, soldiers who selected “Hispanic, Latino, or Spanish Origin” were classified as “Hispanic” regardless of other selections; the remaining soldiers were classified as “non-Hispanic.” Marital status was categorized as married, single, or other (divorced, in a relationship [seriousrelationship, but not legally married], separated, or widowed).

Military characteristics of interest included military rank (enlisted or officer), operational tempo (OPTEMPO), overall job satisfaction, and self-reported likelihood of attrition from the Army. OPTEMPO was assessed using the question, “In the past week, how many hours of work have you averaged per day?” with a scale from 0 to 24 hours and a decline to answer option. Self-reported OPTEMPO was categorized as high (11+ hours) or normal (< 11 hours). Job satisfaction was assessed using the survey question, “How satisfied are you with your job overall?” on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very satisfied to very dissatisfied. For the purpose of analysis, responses to the job satisfaction item were collapsed into 3 categories: satisfied, neutral, or unsatisfied. Likelihood of attrition from the Army was assessed using the survey question, “How likely are you to leave the Army after your current enlistment/service period?” with a 5-point Likert scale ranging from very likely to very unlikely. Responses to the attrition item were collapsed into 3 categories: likely, neutral, or unlikely.

Outcome

Two bogus items were used as indicators of careless responding in the survey. The first bogus item was placed approximately a quarter of the way through the survey and asked “What planet are you currently on?” Response options included “Saturn,” “Pluto,” “Earth,” “Mars,” or “Mercury.” The second bogus item was placed approximately three quarters of the way through the survey and asked “What color is the American Flag?” Response options included “red, green, and white”; “green, yellow, and black”; “red, white, and blue”; “blue, yellow, and white”; and “green, red, and black.” Both items provided the option to leave the response blank. A composite variable was created to categorize responses to both bogus item questions as “pass” or “fail.” If a respondent answered both correctly, then the respondent passed. If a respondent answered either question incorrectly, then the respondent failed.

Statistical Analysis

Bogus item passage (i.e., pass or fail) was stratified by demographic and military characteristics. Chi-square tests were used to identify potential differences in soldiers’ bogus item passage by demographic and military characteristics. Additionally, the relationship between the 2 bogus item questions was examined using a chi-square test to assess whether passing 1 bogus item was associated with passing the other bogus item.

The crude relationship between bogus item passage and demographic and military characteristics was assessed individually using univariate logistic regression. A multivariable logistic regression model was used to determine whether an association existed between bogus item passage and the demographic and military characteristics of interest. Covariate selection occurred a priori based on published literature related to bogus items. Covariates included in the model were sex, age group, race, ethnicity, education level, marital status, military rank, OPTEMPO, likelihood of attrition, and job satisfaction. Listwise deletion was used and p values less than .05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS/STAT software, version 9.4 (SAS InstituteInc.,Cary, NC).

Results

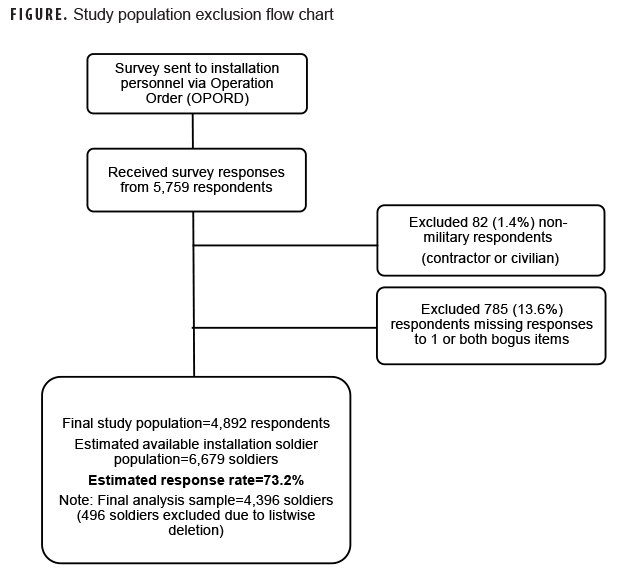

An estimated 6,679 soldiers were eligible for the survey and 5,759 respondents completed surveys during the 1-month data collection period (Figure). Eighty-two respondents (1.4%) were excluded because they reported being either a contractor or a civilian; and 785 (13.6%) respondents were excluded because of missing data on either of the 2 bogus items. The final study population consisted of 4,892 respondents, which represented an estimated response rate of 73.2%.

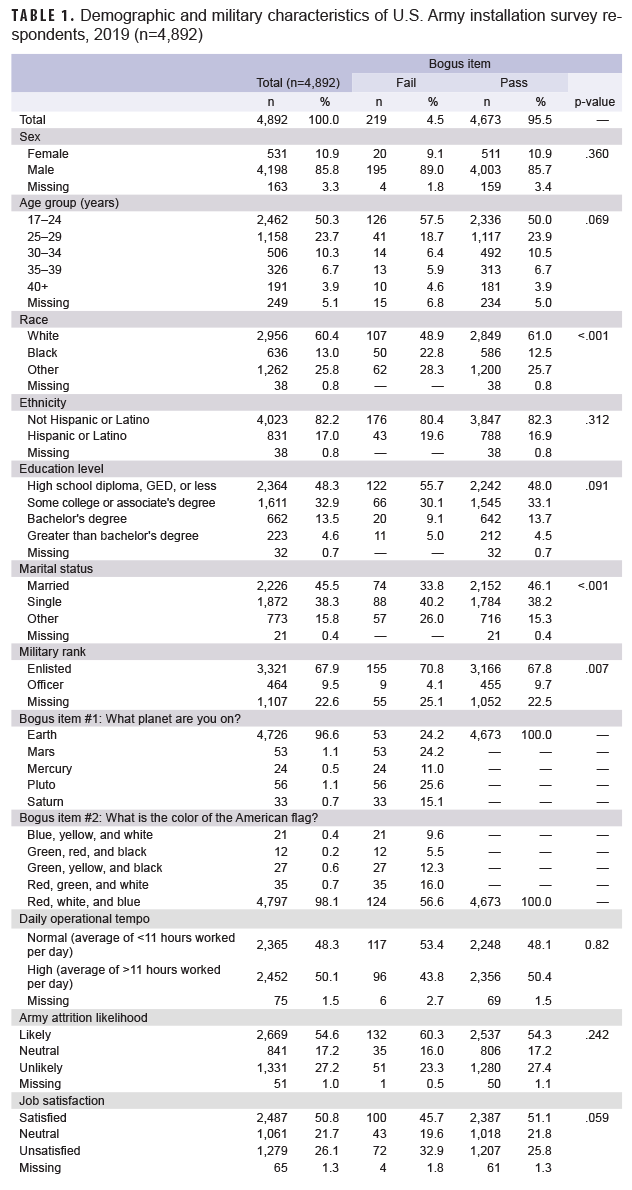

Respondents were primarily male (85.8%), 17–24 years old (50.3%), White (60.4%), Non-Hispanic (82.2%), recipients of a high school diploma or less (48.3%), enlisted (67.9%), and married (45.5%) (Table 1). The overall median response time was 26 minutes (mean=80 minutes; standard deviation=728 minutes; range=1–32,963 minutes). The vast majority (95.5%) of respondents answered both bogus items correctly (“pass”) and 4.5% answered at least 1 incorrectly (“fail”). The first and second bogus items were answered correctly by 96.6% and 98.1% of respondents, respectively.

Respondents’ race, marital status, military rank, and individual bogus item responses were significantly associated with the bogus item outcome at the bivariate level (Table 1). Sex, age group, ethnicity, education status, OPTEMPO, attrition, and job satisfaction were not significantly associated with the bogus item outcome. Respondents who failed the first bogus item had odds of failing the second bogus item that were approximately 30 times (odds ratio [OR]: 29.9, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 19.2–46.5) that of respondents who passed the first item (data not shown).

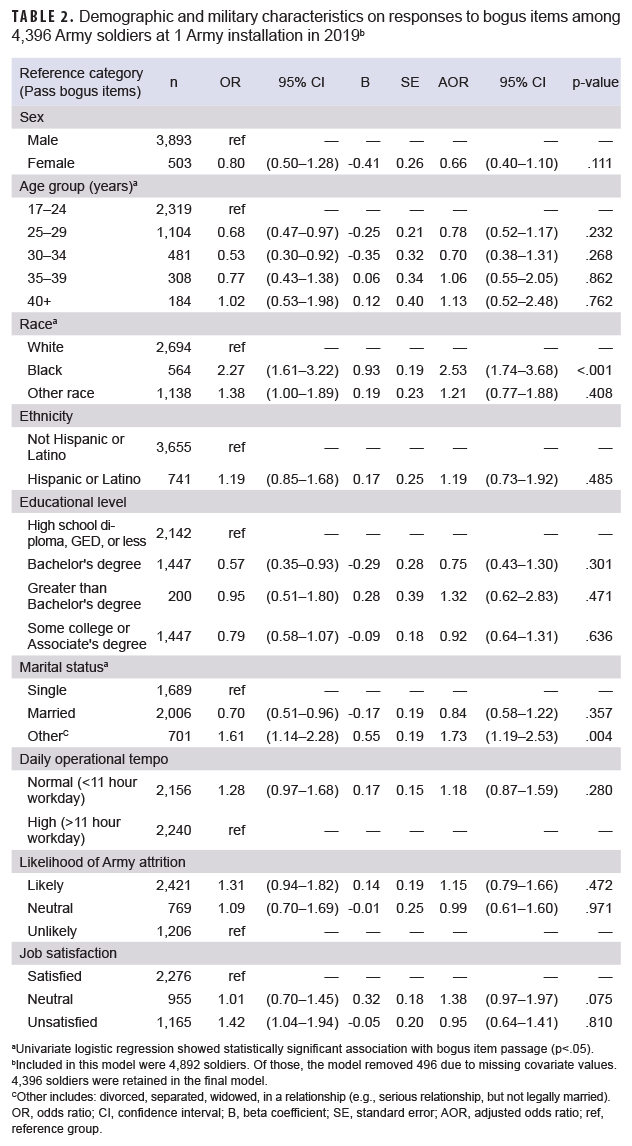

A total of 4,396 respondents (89.9% of the full sample) with complete information for each covariate were included in the adjusted multivariable logistic regression model after listwise deletion. Rank was originally included in the multivariable logistic regression model; however, because this variable was missing for 79.5% of the total listwise deleted observations, it was removed from the final model. Race and marital status were the only variables significantly associated with bogus item passage in the adjusted multivariable logistic regression model (Table 2). Black respondents had odds of failing the bogus items that were more than 2.5 times (adjusted OR [AOR]: 2.53; 95% CI: 1.74–3.68) that of White respondents after adjusting for sex, age group, marital status, ethnicity, education level, OPTEMPO, job satisfaction, and likelihood of Army attrition. Respondents with a marital status categorized as “other” had odds of failing the bogus items that were 1.7 times (AOR: 1.73; 95% CI: 1.19–2.53) that of single respondents after adjusting for covariates.

A sensitivity analysis was performed comparing results of models with and without rank. Results of the 2 models were similar with the exception of the relationship between marital status and the outcome variable; in the model that included rank, marital status was not significantly associated with bogus item passage. Overall, listwise deletion led to the removal of 10.1% of respondents from the multivariable logistic regression analysis. A comparison of those respondents excluded from the model compared to those retained in the analysis showed that the 2 sets of respondents did not differ by demographics or bogus item passage.

Editorial Comment

This study sought to determine the characteristics of careless respondents using bogus items in a survey administered to a sample of U.S. Army soldiers at 1 installation. While it is not feasible to estimate the true prevalence of careless responding across the Department of Defense (DOD) or the Army, this study found that 4.5% of survey respondents failed either of the bogus items and 95.5% passed both bogus items. Prior research estimated the proportion of careless responding in most studies to be around 10% (3%–46%)7,8,11; however, in this study, the proportion of careless responding was lower. The heterogeneous prevalence of careless responding across studies is likely due to the variability in how careless responding is operationalized, differences in survey lengths, study populations used (e.g., AmazonMTurk [online], psychology undergraduate students), and the methods used to categorize careless responding (e.g., data driven methods, bogus items, instructed manipulation checks).7,8,11 The lower proportion of careless responding observed in the current study could potentially be due to reasons such as soldiers being more interested in this survey topic, wanting to make a difference via their responses, command pressure, or responding to bogus items not validated by prior literature.5

This study found greater odds of failing the 2 bogus items among Black respondents when compared to White respondents and greater odds for those categorized as “other” marital status when compared to single respondents. One prior web-based study of 2,000 adults from U.S. households using methods other than bogus items found that Hispanic respondents and unmarried respondents were more likely to be categorized as careless responders in bivariate logistic regression models, although only age and gender were significant predictors of categorization in adjusted models.13 A 2019 dissertation using 1 instructed manipulation check question found that non-Hispanic Black and White respondents had about 1.2 times and 1.1 times the odds of being categorized as careless responders compared to Hispanic respondents, respectively.14 It is unclear why those who reported their race as Black in the current study had higher odds of failing the bogus items, as there are few other published studies that document associations between race/ethnicity and careless responding.13,14

This study was subject to numerous limitations. First, this study only applied 1 method (i.e., bogus items) to determine careless responding. Second, this study did not compare the demographic and military characteristics of the respondents who did not answer both bogus items to those who did answer both bogus items, which could have impacted the interpretation of the results if the 2 were different. Third, listwise deletion led to the exclusion of 10.1% of respondents from the multivariable logistic regression analysis. However, a comparison of those respondents excluded from the model compared to those retained in the analysis showed that the 2 sets of respondents did not differ on demographics or bogus item passage. Fourth, bogus items could reflect careless responding across the entire survey or capture survey inattention at a specific point in time.4,10,15 This study was able to detect careless responding at only 2 specific points in the survey. A combination of methods may be more suitable for detecting careless response bias, such as bogus items, instructed manipulation checks, self-report items, etc. Response time is an inexpensive way to screen for careless responders and assumes a minimum time required to complete the survey; however, there is no clear cutoff point.8,11 Fifth, incorrect answers to 1 question (e.g., “What planet are you on?”) may be less about attention and more about sarcasm, where the responses were influenced by the tone and nature of the bogus question and answered incorrectly on purpose.8,16 A sarcastic comment was indicated by 4 (<0.1%) soldiers in the open-ended comment at the end of the survey. Sixth, no identifying information (e.g., name, social security number, or IP address) was collected. Therefore, it is unclear if respondents completed multiple surveys. In subsequent EPICON surveys, a question that asks, “is this the first time you have taken this particular survey?” has been included to identify surveys completed by the same individual.

Several limitations were related to the bogus items themselves. First, the bogus items employed in this study were not validated by previously published work. As a result, measurement error due to the 2 bogus items may have contributed to the higher pass rate found in this study (95.5%) compared to other studies (approximately 90%).7,8,11 Many studies use bogus items that produce a similar response among all respondents, so that an incorrect response is likely due to careless responding.8 Subsequent articles by Qualtrics on published work from Vannette and Krosnick have shown that the inclusion of bogus items may affect the quality of subsequent answers on surveys.17,18 However, how the bogus items impacted later responses in the current study is unknown. Second, the correct response to both bogus items fell in the middle of each 5-item multiple choice response list. An option to randomize the order of the correct response to each bogus item was not used. Straight-lining (i.e., selecting responses in a predictable pattern) may have occurred and option order bias (i.e., the order of the answer options influences the respondent’s answer) may also have been present. If the first option had been correct, however, the order would have limited the potential for detecting primacy bias (i.e., a greater likelihood to select the first response in a multiplechoice question). Third, soldiers may have responded based on pressure from leaders, a factor which may have biased engagement in the survey. The survey for this analysis did not measure whether soldiers were pressured to take the survey. To adjust for this limitation, a question on leadership pressure has been incorporated into future EPICON surveys. Lastly, the soldiers who responded to this survey may not be representative of the overall U.S. Army or DoD populations, and the findings may not be generalizable as a result.

There are several potential solutions to reduce careless responding among soldiers. First, surveys need to clearly state why the survey is being done and how results of the survey will be used to improve the installation(s). If soldiers are unclear about the purpose and the intent of a survey, careless responding may be more likely to occur.8 Second, multiple bogus items should be incorporated at different points throughout the survey and the correct response order should be randomized.4,10 Multiple methods should be used to estimate careless responding, where possible.4,10,11 Third, if bogus items or other items intended to detect careless responding are used, then the results should be stratified by careless responding to examine if any effect exists due to removing careless responders from the study population.10 Some research has shown that a demographic bias may be introduced if certain demographic groups are more likely to be classified as careless responders and excluded.18 Fourth, a representative sample could be selected instead of targeting all soldiers at an installation. Selecting a subset of the population will reduce survey fatigue by ensuring that only a fraction of soldiers receive each survey.19 Fifth, it should be emphasized that most surveys are voluntary and that duty time cannot be extended to force participation. Lastly, surveys should be pared down to only the most essential questions to save soldier time.8 Decreased survey length assists with improving respondent willingness to participate and may reduce multitasking.

Researchers must thoughtfully anticipate the type of careless responding that may be present in their survey data and use appropriate methods to detect potential careless responses.5,10 Although a small proportion of respondents provided careless responses, careless responding is just one of many types of bias which can pose a threat to survey validity.

Author affiliations: Division of Behavioral and Social Health Outcomes Practice, U.S. Army Public Health Center, Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD (Mr. Smith, Dr. Beymer, Dr. Schaughency); General Dynamics Information Technology Inc., Falls Church, VA (Mr. Smith)

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this presentation are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Department of Defense, Department of the Army, U.S. Army Medical Department or the U.S. Government. The mention of any non-federal entity and/or its products is not to be construed or interpreted, in any manner, as federal endorsement of that non-federal entity or its products.

References

1. Huang JL, Liu M, Bowling NA. Insufficient effort responding: Examining an insidious confound in survey data. J Applied Psychol. 2015;100(3):828–845.

2. Nichols, A.L. and Edlund, J.E. Why don’t we care more about carelessness? Understanding the causes and consequences of careless participants. Int J of Soc Res Method. 2020; 23(6): 625–638.

3. McGrath RE, Mitchell M, Kim BH, Hough L. Evidence for response bias as a source of error variance in applied assessment. Psychol Bul. 2010;136(3):450.

4. Berinsky A, Margolis M, Sances M. Separating the shirkers from the workers? Making sure respondents pay attention on self‐administered surveys. Am J Pol Science. 2014;58(3):739–753.

5. Curran P. Methods for the detection of carelessly invalid responses in survey data. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2016;66:4–19.

6. Johnson J. Ascertaining the validity of individual protocols from web-based personality inventories. J Res Personal. 2005;39(1):103–129.

7. Maniaci M, Rogge R. Caring about carelessness: Participant inattention and its effects on research. J Res Personal. 2014;48:61–83.

8. Meade A, Craig S. Identifying careless responses in survey data. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):437.

9. Oppenheimer D, Meyvis T, Davidenko N. Instructional manipulation checks: Detecting satisficing to increase statistical power. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2009;45(4):867–872.

10. DeSimone J, Harms P, DeSimone A. Best practice recommendations for data screening. J Org Behavior. 2015;36(2):171–181.

11. Huang J, Curran P, Keeney J, Poposki E, DeShon R. Detecting and deterring insufficient effort responding to surveys. J Bus Psychol. 2012;27(1):99–114.

12. Verint Enterprise Experience [computer program]. Melville, NY:Verint; 2017.

13. Schneider S, May M, Stone AA. Careless responding in internet-based quality of life assessments. Qual Life Res. 2018;27(4):1077–1088.

14. Melipillán EM. Careless survey respondents: Approaches to identify and reduce their negative impacts on survey estimates. [dissertation]. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan; 2019.

15. Anduiza E, Galais C. Answering without reading: IMCs and strong satisficing in online surveys. Int J Pub Opi Research. 2017;29(3):497–519.

16. Nichols D, Greene R, Schmolck P. Criteria for assessing inconsistent patterns of item endorsement on the MMPI: Rationale, development, and empirical trials. J Clin Psychol. 1989;45(2):239–250.

17. Qualtrics. Using Attention Checks in Your Surveys May Harm Data Quality. 2017. Accessed 22 September 2021. https://www.qualtrics.com/blog/using-attention-checks-in-your-surveys-may-harmdata-quality/

18. Vannette D, Krosnick J. Answering questions: A Comparison of Survey Satisficing and Mindlessness. In Ie A, Ngnoumen CT, Langer EJ, eds. The Wiley Blackwell Handbook of Mindfulness. West Sussex, UK: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. 2014:312–327.

19. Office of the Secretary of Defense. Implementation of Department of Defense Survey Burden Action Plan - Reducing Survey Burden, Cost and Duplication. 2016. Accessed 22 September 2021. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/pdfs/AD1038400.pdf